- Home

- Brian Falkner

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Read online

Cave Dogs

by Brian Falkner

Book One of the Pachacuta Trilogy

Copyright © 2012 Brian Falkner. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be published in a newspaper, magazine, website or journal.

Foreward

By Daniel Scott

So much has been written and so much has been said, about what happened, but most of it has been nonsense. You hear it, and see it, on television, in newspapers and magazines. People who know nothing about it, express their opinions on radio talk shows. But none of them really know. Their ‘information’ ranges from guesswork to outrageous fantasy.

My name is Daniel, and I am one of those who were there.

I live every day with the memories. There are moments of joy, and long periods of incredible sadness. I wake up sometimes at night sweating in sheer terror.

This is my chance to set the record straight. To let you know what really happened. To celebrate those who lived, and to honour those who died.

This is the story of a bond of friendship. A bond that had existed for some of us for the whole of our lives. A bond that would be tested and tempered in the fires of hell.

I have interspersed my own words with those of Jason, my friend, in the hope of painting you the broadest possible picture of events. I have done this honestly, without editing, even when Jason has not painted a very flattering picture of me.

I have also included excerpts from the journals of Jenny Kreisler, written at the time, and recovered from the caves afterwards.

So here is the truth of the matter. Here is how six kids from Glenfield College became witnesses to (some would say we were instrumental in shaping) one of the most momentous events in history. Except of course, it wasn’t our history. It wasn’t our history at all.

1. Tomo

By Daniel Scott

Only seven of us made it into the tomo before the first tremor.

Jason, Fizzer and Tupai: my best mates since primary school; Jenny Kreisler: the love of my life; her boyfriend Phil; and Dennis Cray, our Sensei, our Bojutsu instructor, mentor and expedition guide.

Dennis had gone in first to set things up and steady the ropes. But it was me who was halfway into the abyss when the earth began to move.

A tomo is basically a hole in the ground. A great big hole in the ground. Sometimes called a sinkhole. There are many tomos scattered across the North Island of New Zealand, but this one was the granddaddy of them all.

10 metres across and 100 metres feet straight down into the bowels of the earth at Waitomo. The walls were lined with native plants that scrabbled for a foothold in cracks and crevices in the sheer walls. Sunlight fell into the tomo, fought a brave but losing battle with the enveloping earth, eventually swallowed by the greedy rock. The base of the tomo, or as far down as we could see, was a misty haze of rocks and bushes.

The Mangapu tomo was a favourite for speleologists, spelunkers, adventurous tourists, and a certain female Prime Minister of this small pacific nation. For the sixteen members of our local Karate dojo the trip was a bonding and confidence-building exercise, but somehow staring into the maw of that gaping fissure into the centre of the earth did not inspire me with much confidence at all.

I watched Dennis’s helmeted head swaying slightly as he slid, surprisingly quickly down the thin strand of the rappelling rope. The tomo might not have made me feel confident, but somehow watching Dennis did. He was the most competent person I knew. The sort of person you’d always want to have alongside you if you were in some kind of sticky situation. He was a fourth dan black belt in the Okinawan Goju-Ryu style of karate that he taught. One of very few New Zealanders who had ever attempted, let alone succeeded at, the 100 man kumite. He was an expert in the ancient Japanese art of staff fighting, known as Bojutsu, and spent his spare time (if he had any) either hanging off the side of a mountain, or scrabbling through caves and rivers deep underground. His wife Reiko, who he had met in Japan, was exactly the same, and both had a kind of stringy, weathered look that came from constantly battling the elements.

I looked up at Reiko, incredibly, heavily pregnant, and noticed her quick glance at the anchor points of the rappelling system. Constantly checking. It wasn’t a sign of nervousness, rather one of confidence. Confidence that came from checking, checking, and when you had finished checking, checking again.

Her waistband radio crackled with the voice of her husband. ‘OK then. Let’s get ‘em moving.’

Reiko smiled at the sixteen students, and first-time cavers, who stood nervously near – but not too near – the platform on the lip of the huge tomo. ‘Who’s up first?’ Her softly accented English was as always a melodious delight.

I noticed Jason suddenly glance at the ground, anxious to avoid Reiko’s smiling eyes. He’d be alright, I thought, once he got started. His only real problem was a lack of confidence. A few others were also staring at the sky, the nearby trees, a sparrow that suddenly darted across the face of the tomo. I cleared my throat and started to raise my hand.

‘I’ll go first.’ Jenny beat me to it. That was Jenny. She had nothing to prove, but was constantly trying to prove it. Probably came from hanging around too much with a bunch of guys, or maybe it was a rub-off from Phil, I wasn’t sure.

Jenny, now securely attached to the rope, standing on the metal grill of the abseiling platform, backed slowly towards the edge. Standing on the lip she glanced backwards and for a moment froze, staring at the spider-web thin lifeline of the rope that slithered down into the darkness.

‘It won’t break.’ Reiko said reassuringly. ‘It has a breaking strain of 300 kilos. It’ll hold a couple of sumo wrestlers quite happily.’

She pronounced the word sumo the Japanese way, ‘smow’, not ‘sue-mow’ as most Kiwis did. Jenny smiled at the image of a couple of giant Japanese wrestlers in their white thong nappies dangling from the end of the rappelling rope, and her rigidity disappeared.

‘Besides,’ Reiko continued with a smile. ‘Even if it did break, the fall wouldn’t kill you.’

‘Really?’ Jenny blinked her surprise.

‘No, it’s the landing on the rocks at the bottom that does all the damage.’

This time Jenny laughed out loud and in the same moment swung her body over the edge.

I confess to some trepidation as I watched the only girl I had ever loved disappear into a hole in the ground. I had known Jenny my whole life, and loved her for most of it, but by the time I was old enough to realise it, it was too late. After this summer it would be way too late.

Jenny was going to be a Doctor. That meant being a medical student for four years. And the University that she had chosen was Otago, near the bottom of the South Island. I was going to Auckland University to study Computer Science, and the distance between the two campuses, although no more than four or five hours by air, was insurmountable for someone like myself who would be scraping through the next three years on what was left of my rugby league money, and a small student loan. Four years at this age is an eternity and I knew that Jenny would be lost to me forever.

If there was any consolation, it was that boyfriend-Phil, my old team captain from the Glenfield Giants, was enrolled in the journalism school at the Auckland University of Technology, and would be just as far away from Jenny as I would be.

It was the same for all of us really. It was the time of change. That no-mans-land between our lives as children and our futures as adults. An air of finality pervaded all that we did. The five of us, six if you included Phil, (whic

h I would prefer not to) had been friends for most of our lives. But the chances that we would be friends for the rest of our lives were very small indeed. Fizzer was going to study philosophy at Massey University in Palmerston North, although he had not enrolled for the coming year, preferring to take some time to ‘find himself’. Tupai had finally signed up, after much urging from Jason, for the Corelli School of Music. Tupai wanted to be a rock musician, but Jason convinced him that a formal music education would give him a better chance of success. Jason himself had left school during the previous year and found a job on a building site. He was better than that, and he knew it, but opportunities for someone with his challenges were a bit more limited.

But even those of us that stayed in Auckland would drift gradually apart. I knew that. We’d get together occasionally on weekends, spend more and more time with our new friends and classmates, and wonder eventually what had happened to each other.

Jenny inched her way down the rope, and eventually Reiko’s radio crackled again with Dennis’ voice. ‘She’s down safely, send the next victim.’

Reiko laughed, a pleasant bell-like trill in the still morning air, her small hands softly caressing her huge belly. ‘The hole is hungry. It must be fed.’

Jason actually took a step backwards at that point, but Reiko saw it, and caught him by the shoulder strap of his wetsuit. ‘You’ll do,’ she said.

I think that she realised Jason’s nervousness, and knew that it would only get worse the longer he waited, so she got him on the ropes quickly. Jason’s descent was slow. He stopped and started a lot. But give him credit, he never panicked, he just kept on going. And going. And going. It was a long way down.

‘Who’s the next sacrificial virgin?’

Nobody moved, but Tupai was nearest so she grabbed his wrist, barely able to get her petite hands around the meaty joint of his arm, and clipped his harness to the rope, showing him again the rappelling moves.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said reassuringly. ‘We never lost anyone yet.’

‘Not true,’ said Phil raising an eyebrow as he always did when he thought he was being clever.

Reiko stopped what she was doing and looked at him. Her expression, far from the supposedly inscrutable Japanese, conveyed quite clearly ‘you don’t know what you’re talking about, and even if you were right this is not the time to talk about it.’ It is amazing what she could put into the lowering of an eyebrow.

‘August and Mallory,’ Phil said importantly. Smart-arsed-ly some would have said.

Tupai looked carefully at Reiko and a few of the other students drew a little closer, with reserved faces.

Reiko smiled. ‘A man who does his research. But I didn’t say nobody had ever been lost, I said we had never lost anyone.’ She turned to the group. ‘Sir Randolph August was a millionaire adventurer in the 1920’s. Graham Mallory was his guide. They disappeared in the Mangapu caving system in 1926. But hey,’ she shrugged, ‘Don’t blame me for that, I wasn’t there.’

I watched Tupai drop away, his massive shoulders bulging under the shoulder straps of the wetsuit as he worked the rope and brake system that was the rappel line.

I liked Tupai immensely. Half Chinese and half Maori, usually mistaken for Samoan, he used to hang around with Jason and me even before Fizzer and his dad moved into the area from New Plymouth.

The youngest kid in a tough family, he had an early reputation as the strongest kid in primary school, a story we’d all gone to great pains to embellish. And as sometimes happens, the myth maketh the man. Tupai had enjoyed the reputation and had done everything he could to make it true. Weights, exercise, fighting with his brothers.

By the time we got to high school the reputation proved to have its drawbacks. The downside of being the toughest kid in the school is constantly having to prove it. Older kids started to pick on him to see if it was true. Without exception they found out that it was. At first he relished this, but he was too smart a person, too much a human being for that to define his life and after a while he started stepping back from fights. He no longer had anything to prove, and I think he quite enjoyed learning the skills of diplomacy and negotiation required to avoid conflict.

He was still the strongest, toughest person alive, as far as I knew, although an all out brawl between his brutal force, and Dennis Cray’s finesse, would be an interesting match up.

Phil Domane slid over the side while I was still musing on the outcome of a no-holds barred match between my friend and my Bojutsu instructor. I didn’t have a lot of time for Phil. He had moved in on my girlfriend while I was away, the year I had played professional rugby league. We hadn’t got on well before that event, and we certainly didn’t get on afterwards. But it wasn’t jealousy that bothered me about him, it was his attitude to others. Internally fragile, he overcompensated by belittling others, as though that would somehow make him more than he was. I suppose really he can’t have been all that bad, as Jenny wouldn’t have stayed with him otherwise, and my view of him is undoubtedly prejudiced, but no question that Phil was one person I would rather not have had along on this subterranean expedition.

Phil took a long time to make the bottom. Longer even than Jason, who had more reason than most to be nervous. Outwardly full of bravado, Phil was terrified the entire time, and I am sure that it was only Jenny’s presence that stopped him from freezing on the rope and having to be rescued.

After that (finally) it was Fizzer who plunged fearlessly over the side. He stopped a few feet below the surface, looked up and caught my eye. ‘Watch this,’ he said with a grin.

‘Just be careful, mate.’ I responded.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘It’s not my time to die.’

He released the rappel and just dropped into the cavity, braking only at the last moment. I am sure the rope smoked the last few feet as he pulled up just short of the tomo floor. Reiko’s eyes narrowed slightly as he dropped, but brightened as he touched down. I was not sure if she was admiring a kindred spirit, or wincing at the antics of an idiot.

Fizzer was sure the Universe had a plan, and that he figured somewhere in that plan. And certainly that plan did not include him splashing his brains all over the rock-strewn floor of a gaping cavern one hundred metres underground. I wasn’t so sure that he was right about the Universe, and its plans for him, but the rope and the rappel brake held, so maybe he was.

There was no real order to our descent, apart from Jenny who had volunteered. The rest of us had just been standing together so we’d formed the first wave of the rough queue. There were ten more students behind me and I’d have been quite happy to have let any of them go in front, but that would have looked cowardly, so I just maintained my best ‘calm-cool-collected’ face as Reiko buckled me onto the line and iterated for the umpteenth time the releasing and braking functions of the rappel and the switch for the helmet light

The edge loomed, and I somewhat reluctantly, but outwardly cheerfully, backed over, kicked off from the platform, and swung down and out into space.

‘Don’t look down,’ had been Reiko’s last instruction to me, so, naturally, I looked down. I had to twist and peer over my shoulder to do it, and I immediately regretted it, but nevertheless it was a sight to rival any wonder of the world.

Floating above the hundred metre drop, suspended by a strand, the darkness below no longer seemed so intense and even the still, light mists of the Mangapu cave seemed less reluctant to give up the secrets lying below.

The first thing I noticed was the river, seemingly right below me, although I knew my landing area was on one of the rocky banks. Plants, bright, and greenly luscious burst from the floor of the cavern. Pancaked rocks formed ledges on the walls that dropped away below. Rocks the size of houses jutted to the sides of my path.

They call it the ‘Lost World’ and if a dinosaur had rumbled across the banks of the river below me I would not have been surprised. There were plants that I could not recognise. The whole place was alien and yet famili

ar.

The tomo was not so much a hole in the ground from here, but a slash in the side of a mountain, and I lowered myself steadily through the rising mist. There was nothing difficult about the rappel, even with just the short half-day’s instruction we had had the previous day. Tourists go down roped to a guide, in case they panic, or freeze, but that wasn’t the point of this trip, so we were doing it by ourselves.

It was hard to judge the distance looking up and looking down, but by my best estimations I was about one third of the way down, about 30 metres or so, when the earth around me gave a half-formed shudder.

Plants shook and droplets of water spun from their leaves. The rope I was clinging to, previously straight and strong, rippled like water and I bounced and spun dangerously close to the razor edges of a clump of the pancaked rocks. I was a puppet, with some demented puppeteer in control far above.

The tremor lasted only a few seconds, and was mild enough that only a little dust and a few stones tumbled into the cave below. Above me I could hear the urgent crackle of Reiko’s radio.

I had shut off my rappel the moment of the tremor, and the second it ceased I was on the move. There was no going up, and bouncing around in the middle of the shaft while the Earth was dancing didn’t seem like a great place to be, so I went down, and Fizzer would have been proud of me the speed I made down that rope.

To be honest, a huge cavern under the ground didn’t seem like all that great a place to be either, but it was preferable to my other alternative.

You have no idea how solid and welcoming the rocky river bank felt as my feet touched down. A strong hand on my shoulder and Dennis’s wise and welcome voice.

‘Well done, Flea.’

I grinned, mainly to hide the residue of the terror, and the fear that more tremors might be on the way while we were stuck underground. ‘I forgot my change of underwear. Does anyone have any spare?’

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

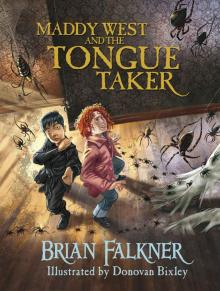

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker