- Home

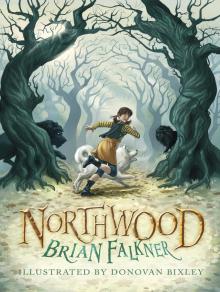

- Brian Falkner

Northwood

Northwood Read online

For my American friends:

Amy, Dan, Evan, and Avery Lynne, Melanie, Molly, and Laurie.

Congratulations to the following people whose names have all been used as the names of characters in this book:

Summer Busch

Harry Mendoza

Anna-Chanel Dolan

Landon Relfe

Danyon Hardie

David Ovink

Matthew Skelly

Natassia Pearce-Bernie

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

1: Cecilia

2: A Cry for Help

3: Rocky

4: The Rescue

5: Safe at Last

6: Helium

7: Up, Up, and Away

8: The Canopy

9: The Clearing

10: Black Lions and Black Trees

11: A Surprise Meeting

12: The Book

13: Orientation

14: Strawbubbles

15: The Happy Hippy

16: Cecilia's Plan

17: Jazz

18: The Expedition

19: The Well

20: The Quarters

21: A Shock

22: A New Plan

23: Tony Baloney

24: Nothing Happened

25: The Party

26: The Drawing Room

27: Naughty Chair

28: Darkness

29: Out of Fear

30: Fist Rock

31: Wise One

32: An Announcement

33: Solving the Mystery

34: What It was All About

35: The End of the Story

INTRODUCTION

THIS IS THE strange story of Ms. Cecilia Undergarment and the black lions of Northwood. It is probably not true, but no one really knows for sure.

Your big brother or sister (if you have one), or your smart-aleck cousin from Wotsamathingitown, will be sure to tell you that it’s not true at all. Which is really like saying that I am telling you lies, because if it is not true, then it is certainly a big fat farty fib. But all I can say is that not everything is entirely what it seems.

Thousands of years ago, everybody (teachers, scientists, government people, even parents) knew that the world was flat. But that turned out not to be true.

Hundreds of years ago, the same smart-brained people knew that the sun and the other planets revolved around Earth. But that turned out not to be true either.

In fact, Earth revolves around the sun. As far as we know for now.

So all I am saying, dear reader, is that you should feel free to make up your own mind about the strange and probably not true story of Ms. Cecilia Undergarment and the black lions of Northwood.

Now, usually at this stage of a story, the person telling the story has some idea of how it will end. But I can tell you quite honestly that I have no idea at all.

So let us go on this strange adventure together.

1

CECILIA

IT IS A slightly odd name — Undergarment. Some people would go so far as to say it is an extraordinary name, which is quite fitting, because Cecilia’s family was one of the most extraordinary families that you will ever meet, even in a story. And they lived in the most extraordinary house, in a small town called Brookfield. Mr. Undergarment, despite what you might think, did not sell ladies’ bras or underwear, but instead owned a balloon factory. He had a specially built house that looked like a big bunch of balloons — the kind you sometimes see in cartoons, usually flying into the sky with a small, frightened boy on the end of the string.

The Undergarment house rose six stories high and bulged out in the middle (as a bunch of balloons should) and was made of balloon-like globes of all kinds of colors. If you saw it from a distance, you would say, There’s a big bunch of balloons tethered to the ground. And if you saw it up close, you’d say, There’s a big bunch of really huge balloons tethered to the ground.

The entrance to the house was a giant red balloon. Not a real balloon, because it would have popped as soon as you opened the front door. But it looked just like a real balloon. Each bedroom was a large blue balloon, because Mrs. Undergarment said that blue was a good sleeping color. All the beds had mattresses made of hundreds of tiny balloons, and were as soft as a cloud to sleep on. The living room was green, with balloon sofas and balloon coffee tables. In the kitchen there were balloon-shaped tables and chairs, and even balloon-shaped pots.

Jana, the housekeeper, cooked most of the meals. But whenever they had a dinner party, which was often, Mrs. Undergarment called Longfellow’s, the restaurant next door. Longfellow’s happily prepared all the meals and floated them over in a basket attached to a bunch of balloons on a long string.

Cecilia spent much of her time in the attic, the highest balloon at the very top of the bunch. It was a clear balloon, transparent like glass, and it made her feel like a princess at the top of a tall tower. She would often lie on the floor and dream of kings and queens in far-off lands, of handsome knights in shining armor, and of elegant balls. Through the clear walls she could see all of Brookfield and beyond: the apple trees in neat rows over at Clemows Orchard; the twin spires of the Church of the Yellow Bird on the island in the middle of Lake Rosedale, where the entire congregation went to church on Sunday mornings by canoe, yacht, or pedal boat; the gray shapes of the elephants and the long necks of the giraffes moving past the fences at Mr. Jingle’s Wild West Show and African Safari Park; and the mist-shrouded forest and black-capped mountains of Northwood.

It was said that no one who entered Northwood Forest ever returned, and that no one who had gone in to search for them had ever come out either.

Cecilia tried not to look in that direction. The trees of Northwood often seemed to be human, and sometimes they even seemed to be calling out to her. Although she knew it was just her imagination, it unsettled her to think of that dark, brooding mass just a few miles north of her house, and what would happen if the mist that surrounded the forest lifted, and whatever lurked there was set free.

There’s not much more you really need to know about Cecilia Undergarment. She really was a perfectly normal girl. At least, as perfectly normal as anyone who lived in a balloon house near a dark, enchanted forest could be.

And as normal as anyone who could talk to animals.

2

A CRY FOR HELP

THAT’S NOT ENTIRELY true, about Cecilia talking to animals. But it’s not entirely untrue.

Anyone can talk to animals, and most people do. They talk to their dogs and cats all the time. Some people talk to their guinea pigs or their parrots. Other people even talk to trees.

The thing that is a little unusual about Cecilia is that the animals talked back.

Not in English or French or any other human language, but in their own animal languages — in woofs and meows and clucks and chirps.

Even that is not too strange, since many animals talk to their owners. Cats have a certain kind of meow that means, Where’s dinner?, and dogs have a hundred ways to say, I’m happy to see you. Where have you been for so long?, even if you’ve only gone down to check the mailbox at the end of the driveway.

But what made Cecilia a little special, quite extraordinary, in fact, was how well she could understand what the animals were saying.

A certain kind of bark, combined with a particular expression on a dog’s face, plus a certain wag of the tail, and Cecilia knew without a doubt that the dog was saying: Look at my owner. What a pickle-brain. He takes me to the park and walks me around each day, hoping that some nice young lady is going to stop and comment on how beautiful my coat is, and that will lead to coffee, then dinner, and eventually to the

wedding chapel.

And a slight change in the expression in the dog’s eyes and the tone and length of its bark, and it was saying: But whenever anyone does stop to compliment me, he is always too shy to say anything but “thank you” and just walks on. What a pickle-brain!

Not only could Cecilia talk to and understand animals, but she had also learned some of the few hidden truths about dogs: they are much smarter than they seem, and they often don’t think very much of their owners, but they love them just the same. They tend to regard their owners the way a parent might regard a slightly rebellious child.

It must be a matter of constant surprise to dogs that humans never actually get any smarter and just keep making the same mistakes over and over again. Of course cats figured this out years ago, which is why they treat humans with such contempt.

Cecilia knew all this, but she also knew not to let anyone know that she could understand what animals were saying. In some deep, secret place inside her, she realized that this was special and private.

She knew this the same way that birds know how to fly without anyone ever teaching them and that dogs know how to lift their legs when they go pee.

Usually in a story like this, the hero (that’s Cecilia) is an orphan. The hero often lives with her evil stepmother or her wicked aunt and uncle who don’t care about her one bit and devote all their attention to their own disgusting son or daughter.

But this was definitely not the case with Cecilia.

It’s true that she lived with her father and her stepmother, but her stepmother loved and cared for Cecilia very much, and was only a little bit odd. Cecilia loved her too, and had always called her Mommy. She had never met her birth mother, who had died when Cecilia was born.

So Cecilia lived very happily with her dad, her stepmom, and their housekeeper, Jana, who loved everybody and still had love to spare.

***

Cecilia’s strange adventure began on a Friday afternoon. That was often a sad time for Cecilia because school was over for the week. Cecilia loved school. She loved her friends and she loved to play Duck, Duck, Goose at recess and Four Square at lunchtime.

She liked her teacher, Mr. Treegarden, who rode to school on a rickety old bike that went clickety-clack. He always called out “Nice to see you!” as he passed Cecilia skipping along Strawberry Lane, and Cecilia would always call back “To see you, nice!” as Mr. Treegarden bumped his way over the cobblestones to school.

Cecilia especially liked learning new things, and at school they were always learning lots of new things. She knew how to do long division and how to spell rhododendron (which is a particularly hard word to spell) and that Reykjavik is the capital of Iceland and that Earth revolves around the sun. (Which is true, as far as we know.)

But this Friday Cecilia wasn’t feeling sad.

She was quite excited because she was invited to a birthday sleepover at her best friend Kymberlee’s house on Saturday. She would not make it to that party, but she didn’t know that yet.

Cecilia was reading a new book that her father had bought her, all about King Arthur and the beautiful Queen Guinevere, when she heard the noise.

She closed the book for a moment, listening carefully with both her ears.

There it was again. A distinct but distant bark. A distressed bark.

To really understand what dogs were barking about, Cecilia had to see the animal, because the sound of the bark was only part of the language.

Still she knew, from the tone of the bark, that something was terribly wrong.

Cecilia walked over to the transparent wall of the attic and looked out.

Just at that moment, the dog barked again.

She saw it immediately.

It was Mr. Proctor’s dog, a beautiful Samoyed — the long-haired, white, Siberian sled dogs that are often mistaken for huskies. It was standing with its front paws up against the window on the top floor of Mr. Proctor’s house.

The Samoyed barked again, and this time Cecilia understood it perfectly. The lowering of the ears, the widening of the eyes, the way its head moved, plus the sound of the bark. She understood it as well as if it had spoken in English.

“Help me!” the Samoyed said.

3

ROCKY

YOU ALREADY KNOW that on one side of Cecilia’s house was a restaurant. What you don’t know is that on the other side was a little old house, in which lived a little old lady who wore too many hats and her bloomers on the outside of her pants. And behind Cecilia’s house was an enormous mansion, three stories high, which was still only half as high as the Undergarment balloon house, but was still pretty big.

In that house lived Mr. Proctor, the grocer. He wasn’t really a grocer, although he used to be. Three years before, Mr. Proctor had turned his little corner grocery store into a superstore. It was called ProctorMart and it was one of those everything shops.

Along with fresh produce and groceries, it sold clothes and shoes, medicine and books, pots and pans, computers and TVs and cell phones, and just about everything you would ever want to buy.

When Mr. Proctor was a grocer, he was a ruddy-cheeked, big-bellied, teddy bear of a man, with a brown beard and a huge smile. He was always offering little samples of bread or cheese to the children who came into the shop.

And if ever anyone didn’t have enough money to pay for their groceries, he would just laugh and say, “Pay me next week.” And sometimes, if he knew they were really poor, he wouldn’t worry about it at all.

But when he opened his superstore, he changed. And as the superstore grew larger, Mr. Proctor changed some more.

He shaved off his beard to look more professional. He bought seven different exercise machines, which did a lot of exercise for him, and he lost one hundred pounds. He went from being a jovial, bearded, fat grocer to a thin, greedy businessman in the span of just twelve months.

The smaller stores in Brookfield began to close down. They couldn’t compete with ProctorMart’s cheap prices. As they closed down, all their customers were forced to shop at ProctorMart, whether they wanted to or not.

And no longer did anyone get anything for free from Mr. Proctor, even though he could afford it much more than before.

Mr. Proctor had a wife, Adelia, and a daughter, Jasmine. Adelia had been a tall, happy, rather messy woman — big and wobbly, but in just the right places. She was often seen striding down the main street with a huge smile on her face, greeting everyone she met like a long-lost friend.

But when the grocery market changed into a superstore, and the big, bearded grocer changed into a thin, selfish businessman, Adelia’s life changed too.

She was no longer seen happily marching down the main street; she seemed to shuffle, and the greetings she received were no longer very pleasant. Some of them were angry and some of them were sad.

Then one day, she and Jasmine left and did not return.

After that, Mr. Proctor began to act in ways that were more than just selfish . . . more than just greedy. He began to torment the people (and animals) around him.

And he lived right behind Cecilia’s house.

***

Cecilia pressed her nose right up against the transparent wall of the attic and looked down at the dog. The wall pushed back against her face, squashing her nose, which probably made her look quite funny — like a squashed melon or an alien octopus.

But the only living thing that could see her funny-looking face was the beautiful Samoyed on the top floor of Mr. Proctor’s house, and he (or she) clearly had more important things to worry about than whether Cecilia’s nose was squashed like a pancake that hadn’t been flipped properly.

“What’s wrong?” Cecilia shouted down at the dog. It looked up at her quizzically. She pressed her hands around her mouth, right up against the wall, and called out to it again at the top of her voice.

Still th

e dog could not hear her, so she went out to the balcony.

The balcony encircled the attic and offered the most spectacular views across the countryside — even better than from inside the attic itself. When Cecilia pretended to be a princess, like in her books, it was always here that she would come to stare out at the kingdom and to bestow blessings on her subjects.

It was a little windy, but the balcony had a high safety railing, so she was not concerned.

“What’s wrong?” she called down to the dog.

“I’m hungry,” the dog called back up. “Starving.”

“Are you sure?” Cecilia asked. She didn’t want to be rude, but she knew that dogs were prone to exaggeration, especially about food.

“I’m starving to death!” the dog replied. There was something about the look in the animal’s eyes that told Cecilia it was indeed true.

“What’s your name?” Cecilia asked, while she thought about what the dog had said.

“Rocky,” the Samoyed said.

“Are you a boy dog?” Cecilia asked and Rocky woofed a quick yes.

“Well,” Cecilia started, careful not to sound rude, “why don’t you just ask your owner for some food? He owns a big store, and I know they sell dog food. I am sure he will feed you if you ask.”

Rocky gave her a look that would have made Cecilia feel a little silly, if not for the terribly sad look in his eyes.

“I have asked and asked and asked. When Mrs. Proctor was around, she always fed me, because I was her dog. But since she left, no one feeds me. I am only alive now because of the little scraps of food that old Aunt Beatrice drops from the table by accident. And because I lick food off the plates in the dishwasher when they’re not looking. Plus I find some in the garbage can.”

“Oh my word,” said Cecilia. It wasn’t the sort of thing she’d usually say, but it sounded quite appropriate for the circumstances. “Oh my word, that’s truly horrible! How could someone treat such a beautiful dog that way? How could he treat any dog that way?”

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

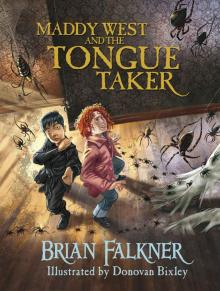

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker