- Home

- Brian Falkner

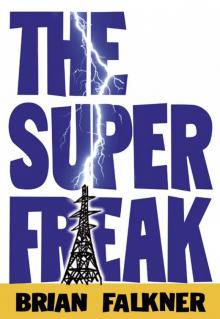

The Super Freak

The Super Freak Read online

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Logo

Forward: Mind Matters

Words of Wisdom

The First Clue

Detention

The Artificial Kid

GWF

My Dad

What I Did in the Holidays

The Lightning Tower

The Dream

First Crime

Super Freak

Crikey

The Student Council

Erica McGorgeous

The Election

The Old Stump

Assembly

The Navy Destroyer

Frosty the Snow-Girl

Second Crime

:-)

Dumbo Gumbo

Will Bender

Turning the Tables

My First Date

Dry Run

Detention Times Two

Catastrophe

Spring Fever

Crime Time

Ill-gotten Gains

The Getaway

Fingerprints

The Pylon

The Big Game

Epilogue

Appendix: Wise and Wonderful Words

Author Note

About The Author

Copyright

Dedication

Also by Brian Falkner

STRANGE THINGS ARE HAPPENING AT GLENFIELD HIGH AGAIN. THIS TIME IT’S JACOB JOHN SMITH’S TURN …

‘My name is Jacob John Smith, and this is the story of the crime of the century.’

Jacob John Smith is tired of getting into trouble. He’s fed up with being pushed around and hassled by Blocker – the school bully.

But then he discovers he has a power. Will he use his power to be a superhero? Or perhaps a supervillian? Either way, life for Jacob is never going to be the same again.

A mind-bending adventure.

ONE

FORWARD - MIND MATTERS

Where do thoughts come from?

You know, like you’re sitting in Maths and the teacher is droning on about isosceles triangles, and suddenly into your mind pops the thought that you’d really like a big date scone with jam and whipped cream. Which has nothing to do with isosceles triangles.

Or you’re sitting on the bus on the way home from school and all at once you imagine that the bus is going to lift off the ground like a UFO and fly out into orbit.

Where do thoughts like that come from? I don’t know. I’m not a scientist, or a psychologist or anything like that. I’m just a kid. But I do know where some thoughts come from. Like the time that Frau Blüchner in French class wrote ‘knickers’ on the board instead of ‘naître’. I know where that thought came from. It came from me.

Perhaps I should explain. Let’s start with this: my name is Jacob John Smith, and this is the story of the crime of the century.

TWO

WORDS OF WISDOM

The English language, I decided, was full of long, wise and wonderful words, which were rarely used, even by teachers. As a full-time native speaker of the language I felt it was my duty to use most of these words as often as possible, and all of them at least once in my life.

So, after four schools in four years, the library and the dictionary were my best friends.

It isn’t easy shifting schools. I had started school with a couple of mates from kindy, and was happily ensconced in primary school through the ages of five, six, and part of my third year, when, just after my birthday, my dad’s company shifted him from Oamaru to Ashburton.

‘He’ll make friends easily,’ they said; they being everyone from my mum and dad, to my new teachers, grandparents and assorted aunts and uncles. Only it wasn’t easy. Kevin and Mike, my absolute best mates in Oamaru, came to see me off when we left for Ashburton one Saturday morning in July. They waved, and I waved back and thought about how much I was going to miss them, but I waited until they were well out of sight until I cried. And I kept crying the whole way to Ashburton, despite my big sister April threatening to thump me, and Mum eventually saying that if I didn’t stop it I would miss out on McDonalds for lunch, and Dad saying that if I didn’t shut up he was going to leave me on the side of the road.

Even Gumbo, the family dog, lay on the back seat in between April and me and put his front paws over his ears.

April thumped me. I missed out on McDonalds (we had a dry, papery sandwich from a roadside café instead), but I didn’t get left on the side of the road. Things might have been different if I had.

They gave me a school-buddy at Allenton Primary in Ashburton. That’s a kid who is assigned by the teacher to show you around. I think the idea is to help you get to know people and make friends.

The only problem was my school-buddy was a creep named Alex Kerkoff, and you could have found a worse school-buddy, but it would have taken a lot of trying. I don’t know why he was assigned to me. Maybe it was a punishment, or maybe it was just his turn.

The first lunchtime, Alex showed me where the toilets, library, and sick room were, then disappeared to play some stupid trading card game with his friends. I sat around on a wooden bench for a while, looking at the wintery drizzle and, after a while, I found my way to the library.

At the end of lunch break, Alex was waiting for me outside the classroom door, and we walked in as though we had spent the whole lunchtime together. As if we were buddies. Only we weren’t.

I did make friends, though, eventually, Sam and Niwa. Andy too, I suppose, and Christian Jobson, although he was in another class. Not quite close friends, like Kevin and Mike had been, but good mates all the same.

So, you can’t imagine how devastated I was when my mum and dad announced to me, not much more than a year after we’d arrived in Ashburton, that he’d been promoted and we were moving to Wellington.

My name is Jacob John Smith, and that’s an unfortunate name in some ways. John was my father’s name, and Jacob was just a name my parents liked. But there’s a kids’ song called John Jacob Jingleheimer Smith, and my name was just a little too close to that for comfort.

In my third primary school they used to walk past the library singing it but changing the lyrics to something much ruder.

John Jacob Jingleheimer Smith, his name is your name too.

And you’re such a smarty pants,

You’re a real farty pants.

Go home John Jacob Jingleheimer Smith.

I said it was rude. I never said it was clever.

The library, which had been my retreat from boredom, became my refuge from their taunts, from their derision. It became my castle.

I didn’t make any real friends in Wellington, but I was only there for eighteen months. Dad worked for a nationwide network of radio stations and, when they were bought out by some overseas company, half the staff – including Dad – lost their jobs. So, we shifted again, this time to Auckland. I’m sure I would have made some friends if I had stayed in Wellington a bit longer. I’m quite sure of that. Quite sure.

We shifted over Christmas and I think that helped because, when I started at Glenfield Intermediate, I wasn’t the only stranger. The kids were from lots of different primary schools and, because I started at the beginning of the year, I didn’t have to break into a class mid-year.

I made friends almost immediately with a red-haired firecracker of a boy named Tommy Semper. We got along great. We had the same sense of humour, liked (or didn’t like) the same sports, and generally had a good time whenever we were around each other.

Only thing was, he didn’t return to school after the first term holidays. This time it wasn’t me that was transferred away, it was him. Tommy’s father was a representative of a big Italian firm, and he got recalled to Italy. The first I kne

w was when Mrs Abernethy, our teacher, called out the roll at the start of class on the first day back. I wanted to skip class that day, I felt sick. But I wasn’t really sick, and no amount of pleading would convince Mrs Abernethy otherwise. It occurred to me, possibly for the first time, how my life was completely out of my control. People told me what to do. Things happened to me. I had no say in anything. I was just a leaf swept up in a storm.

Andrew Allen transferred into our class during that term, his family had moved up from New Plymouth. For the first couple of weeks he looked as lost and lonely as I was. I didn’t try to make friends with him, though. Friends moved away. They hurt you, and it wasn’t even their fault. Two long years at Intermediate School and I managed to get though them without making a single friend.

The only thing you could rely on, the one thing that was always there, was the library. And the library was full of books, and the books were full of words. Long, wise and wonderful words.

THREE

THE FIRST CLUE

The first time I got a clue was in PE.

Physical Education it stands for, although, personally, I thought Persecution and Excruciation were more appropriate. High School was a big change from Intermediate, in many ways, some for the better and some for the worse. One of the worse was PE. Old Mr Saltham, who had been in the navy, was in charge of the Persecution & Excruciation department, and he took our class for PE.

Mr Saltham, ‘Old Sea Salt’ we called him, because of his time in the navy, barked orders as though you were deck hands. If you didn’t succeed at something he’d make you do it again, and if you simply couldn’t succeed at something he’d make you keep trying until you’d humiliated yourself in front of the whole class, and then he’d give you detention.

I’m going to be fair here and admit that this approach actually worked on some kids. Some kids who were lacking in confidence would end up succeeding at something they didn’t think they could do, and that gave them the confidence to try other things they didn’t think they could do and before long they were into everything; so Old Sea Salt did have some success.

However, that was some kids. Not all kids. For many of us, and you’ll notice that I said us, Saltham’s tactics were terrifying and made us even more convinced that we were useless at anything physically demanding.

Old Sea Salt was short and wiry and what little hair he had was cropped close to his scalp. He may not have been all that tall, but he seemed twice the size when he started shouting. I suppose he was used to dealing with a tough bunch of sailors, so kids like us were easy meat.

One of Saltham’s favourite exercises was a version of bullrush. It was a bit simpler, though, and much more violent. He’d line up half the class on one side of the gym, and the other half on the other side. In the dead centre of the floor was a big circle which was something to do with netball. When he blew his whistle, everybody had to run to the other side of the hall. But they had to run through the circle. It was like rush hour on one of those Japanese commuter trains where they pack people in like sardines, only half the people were running in one direction, and the rest were going in the other. If you were on the outside you risked getting bumped out of the circle and having to do push-ups. If you were on the inside it was like being crushed in a lemon squeezer.

The last time we had done the exercise I had been on the inside. That was tough, because I was one of the smaller kids in the class and behind me I’d had a couple of the biggest, while in front of me, going the other way, had been the captain of the rugby league team, Phil Domane, and his huge mate (and star league player) Blocker Blüchner. I’d been squeezed between the two sides until I thought I was going to pop up into the air like an orange pip you squeeze between your fingers. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t even get enough air into my lungs to scream, which was probably just as well as they would have thought I was a wuss, and I would have got detention as well.

Just when I’d thought I was dead, the pressure from behind had squeezed me through a small gap between Phil and Blocker and, after taking an anonymous elbow in the side of the head that made my eyes water, and bouncing off a few other guys, I was finally through and over to the other wall.

That had been a week earlier. Now it was PE again, and I was scared out of my wits that we were going to have to go through the same thing. Only this time I might not be so lucky. This time I might not survive.

The lesson was just all the usual tortures until the last few minutes. We had finished a long arduous exercise that involved throwing around medicine balls, and had packed the gear away. Then we just milled around for a moment wondering what Old Sea Salt would set us to do for the last few minutes of the period.

He walked to the centre of the hall, in the middle of the netball circle and looked at us. There were just four minutes left in the period. Saltham never let you go early; it would be undisciplined. I could see him considering, and I knew he was going to make us do the bullrush exercise.

Don’t do the bullrush exercise, I thought at him desperately, trying to will him not to. Let them all go early. I thought it over and over, staring at him, as if somehow I could make up his mind for him.

‘That’s enough for today,’ he said at last, glancing up at the clock on the wall. ‘Off you go, get changed, see you on Thursday.’

Everybody rushed for the changing rooms, surprised beyond belief. But as Old Sea Salt walked past me, staring straight ahead, I thought he looked a little surprised as well.

I didn’t think much of it, though. Just lucky, I thought.

Until the next time.

FOUR

DETENTION

It was Thursday. The next time was still a couple of days away. It was sunny and warm, after a long wet spell, and some kids were spinning around on the school fields like puppies chasing their tails, having too much fun to head off home, even though school had finished.

Not me though. I was in detention. Again.

Now, I don’t want you to get the wrong idea here. I don’t want you to start thinking that I was a bad kid. I mean, sure, I seemed to spend a lot of time in detention, and I’d been called into the Principal’s office for a stern talking-to on more than one occasion, and I was ever-grateful that they’d outlawed the cane many years ago, but it was almost never my fault.

You know how some kids just seem to attract trouble? Well, I was one of those kids. And I don’t care if you believe me or not.

OK, maybe I did do a few bad things at the beginning, like the joke with the water balloon, the roll of toilet paper, and Mrs Rossler’s handbag, but she’d deserved it anyway for making fun of me in history. And if I’d been sensible, I’d never have done what I did with the school’s prize-winning totem pole, but it was really funny and I hadn’t thought I’d get caught. And, yes, there were a few unauthorised chemistry experiments involving some talcum powder and the school cat.

But it was all just fun stuff. I was not a bad kid.

I’m not saying I was perfect. I wasn’t a genius like Amy Spring, who’d won the national Mathex competition, or a school hero like Blocker Blüchner, the try-scoring front row forward of the under fifteens school rugby league team.

But I certainly didn’t deserve all the crap that seemed to come my way.

So, there I was, sitting in detention, pen in hand, paper in front of me, looking out of the window watching Phil, Emilio and Blocker kick a football around on the top field. I lowered my eyes and flashed evil thoughts at Blocker, and he dropped an easy catch, which made the others laugh. Good, I thought. I wouldn’t even be in detention if it wasn’t for Blocker.

He had chucked a flask of potassium permanganate solution (that purpley stuff) halfway across the science lab to me when the teacher wasn’t looking, but I had fumbled and dropped it. It had smashed and gone all over Tom Prebble’s schoolbag and, somehow, I had ended up taking the rap.

Of course I had protested my innocence, but he was the star of the league team, and I was a known troublemaker. So, wh

o were they going to believe?

I turned back to my detention assignment. I had to write an essay on capital punishment in New Zealand, the pros and cons. Capital punishment, if you don’t know, is the death penalty for serious crimes like murder.

I wasn’t quite sure why they’d chosen that subject for the detention essay. Maybe it was a kind of threat. Maybe they were thinking of introducing it at Glenfield. I decided that I’d better write an essay strongly opposed to capital punishment, just in case.

I looked around the room. There was only one other kid in detention today, Toby Watson. He was staring at his blank refill pad with a panicky expression on his face. I don’t know why writing essays terrifies most kids. All you have to do is decide what your opinion is, then express it clearly in nice simple words that even teachers can understand.

I also can’t understand why they use essays as a punishment. I really enjoyed writing essays, but it seemed as if the teachers were saying writing was a bad thing, a thing so horrible that you’d only do it as a punishment.

Then they go and complain that it’s hard to get kids to write stories and stuff nowadays. Go figure!

Four o’clock came and I had long finished my two page essay. I walked out past Toby, who had only done half a page, and put it on the teacher’s desk as I left.

The next day my life changed for ever.

FIVE

THE ARTIFICIAL KID

What if there was this giant American corporation that made robots? A really secret corporation which made top secret test models for the US Army or the CIA; robots that looked just like human beings. And what if this corporation made a robot like a kid? An artificial schoolkid. And maybe they wanted to see how well the robot would do if it was put in a class of regular kids. To see if the other kids noticed.

I know it sounds a bit far-fetched, but what if it were true?

Ben Holly was thirteen years old, he was in my class for French and Science, and I was sure he was a robot.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

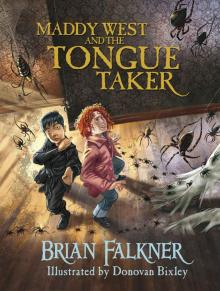

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker