- Home

- Brian Falkner

Clash of Empires Page 10

Clash of Empires Read online

Page 10

“With a daring and wily captain,” Thibault says. “And a plan that nearly worked.”

“Not nearly enough,” Cochrane says. “I confess I did not see your trap before you sprang it, and I am still confounded as to how you maneuvered those two warships onto my stern.”

“The Canard and the Mouette are not men-o’-war,” Thibault says. “Merely cargo ships, lightly laden. They carry no cannon.”

“But…” The realization sinks in. Cochrane closes his eyes and lowers his head for a moment. “I could have escaped at any time, if only I had known.”

“If only you had looked a little more closely,” Thibault agrees.

“At risk of seeming discourteous, we must to business,” Cochrane says. “I have many wounded. Our surgeon was killed. I trust you will allow your surgeons to treat my men.”

“Alas, our surgeons are busy with our own wounded,” Thibault says.

“Of course. Then I ask that they treat my men as soon as they are able,” Cochrane says. “In the meantime, if you will release my ship’s carpenters, I will have them start to repair the damage. I am afraid we will have to lose the mainmast, but she will sail well enough with the two remaining.”

“She is badly damaged,” Lavigne observes.

“Yet repairable,” Cochrane says. “And as I said, a good prize.”

“We have no need of prizes,” Thibault says. “Not even a proud and lucky ship such as the Antelope. Had you struck your colors earlier and left your ship undamaged we might have joined her to our fleet. But we have no time to stop for repairs.”

“You will scuttle her?” The captain looks sadly over the railing at the ship. “I will miss her.” He sighs. “And you have my word as a gentleman that my crew will give you no problems when you bring them aboard.”

“Indeed they will not,” Thibault agrees.

Cochrane frowns as he watches two French seamen on the frigate emerge from belowdecks carrying gunpowder barrels. Other sailors are lashing shut the hatches to the lower decks. It is so unthinkable that it takes a few seconds for him to comprehend what he is seeing.

Finally the awful truth dawns and his face turns ashen. “You pirate!” he cries. “You blackguard! This is—”

He says no more as he has no air with which to do so. He looks down at the hole in his chest as the sound of Thibault’s pistol echoes off the masts. Cochrane’s eyes fix on Thibault’s and remain there even as his body collapses to the deck.

Captain Lavigne turns away with a look of disgust.

“Captain Lavigne,” Thibault says.

The captain turns back with gritted teeth. “Over the side with him?” he asks. “Or shall we let the captain burn with his ship?”

“Neither,” Thibault says. “Send for the butcher. Let us see if the girls like the taste of British nobleman.”

* * *

The rain has stopped and the sun strikes the sails of the French fleet, full and rigid with good wind, as the ships leave the wreck of the frigate behind. A fuse on board reaches its end and the gunpowder poured liberally over the decks ignites. Within seconds the wooden hull of the once proud and lucky ship is ablaze, the roar of the flames almost, but not quite, drowning out the screams from belowdecks.

SMALL JOYS

The sun is warm on her skin as Cosette takes the path to the spring, the source of the stream that runs past the abbey. The only other washing facilities are the troughs used by the soldiers, and neither Cosette nor Marie Verheyen will use those if they can help it.

It is a short walk through the forest to the jut of stone that forms a small rock pool. The water wells up on one side and escapes over a low lip at the other.

It would be so easy to run away, Cosette thinks whenever she is outside the old stone walls of the abbey. But if they caught her they would beat her and never let her outside the walls again. And if they didn’t catch her, they would execute Madame Verheyen.

She is almost at the pool when she stops and turns, convinced that someone is on the path behind her. But no one is there. She examines the trees on either side of the path, but there is no sound, no movement. After a moment she continues on, not quite able to shake the feeling that someone is watching her.

At the pool she wets her cleaning cloth and washes her face and hands, glancing around one more time before undressing to take her bath.

She removes her dress and launders it in the pool, then lays it on a rock in the sun to dry. She does the same with her smalls, then steps up to her knees in the water, as deep as she dares. The spring water, from far underground, is icy.

This is a small joy. The fresh cold water, the heat of the sun on her skin. Such simple things, amid the terror and horror that surround her.

She washes the muck and mud from her skin and hair, and has almost finished her bath when she hears a cough behind her. Instinctively she plunges into the deepest part of the pool, crouching, immersed up to her neck. The cold burns like fire on her skin.

It is Belette. He has picked up her dress from the rock and is studying it with his one eye.

“My apologies, mademoiselle,” he says. “I did not expect to find anyone here.”

“But I am here, monsieur,” she says. “And as you can see, I am not respectably dressed. I would ask you to leave.”

Belette shakes his head. “That would be unwise,” he says.

“Unwise?” It is freezing in the water. After just a few seconds Cosette is already shivering badly. Her teeth chatter so strongly she fears they will chip or break.

“Mademoiselle, you should have someone here to protect you,” Belette says. “There could be wild animals or saurs roaming through the forest.”

“This close to the abbey? I do not think so,” Cosette says. “It is patrolled by your men.”

“Who is to know what lurks in the forest?” Belette says. “It is not safe for you here alone. And our soldiers have not seen a woman for many months. What might they do if they found you alone and unclothed?”

“It is kind of you then, to have such concern for me,” Cosette says. “Please turn around so I can come out. I have finished my bathing and am getting cold.”

That is less than the truth. Her body is now shaking violently, as people do when they have been too cold, too long.

“Of course, mademoiselle,” Belette says. He places the dress on the rock and turns to face the forest.

“You will not turn to look,” she says.

“I give you my promise,” he says.

Cosette remains in the water despite a growing numbness throughout her body.

“Mademoiselle?” Belette asks, without looking. “You will freeze if you stay much longer. Why do you remain in the water?”

“Because, monsieur, I fear that as soon as I stand up, you will break your promise.”

“Mademoiselle!” Belette seems offended. “Have I ever given you reason to suspect I would go back on my word?”

“You have been watching me since I arrived at the spring,” Cosette says. “I sensed you in the bushes.”

“I swear I have not,” Belette says. “I left the abbey only a moment ago. Perhaps it was someone else you sensed in the forest. Or some wild animal. But fortunately I am here now to protect you.”

His hand drops to the hilt of his sword and he loosens it in the scabbard, still facing the forest.

Cosette is silent. She eases herself up out of the water as quietly as possible. She takes two quick strides toward the dress but he snatches it up before she can reach it, then turns to face her.

“You scoundrel,” Cosette says, covering herself as best as she can with her hands. She is shivering violently and, although she wants to dive back into the concealing water, she knows she cannot; she is dangerously cold now. Besides, what is the use? He has already seen her unclothed. Her honor is already lost. Instead she crushes an arm across her breasts and a hand over her privates and spits at him, “You are a man of no morals. Give me my dress.”

“There are man

y things that a young lady must learn in life,” Belette says. “For example, that it is easier for a liar to pretend to be a truth-teller, than a truth-teller to be a liar. You should be grateful for this lesson. And of course I will let you have your dress back. If you earn it.”

“I will do nothing,” Cosette says, although Marie Verheyen’s words now echo in her head: This ordeal will end. Do whatever you have to do to survive.

“But you will, if you want your dress back,” Belette says. “Perhaps a kiss. Just a simple kiss. Would that be so bad? I have always been kind to you. Given you things. Protected you from the other soldiers.”

“I will not,” Cosette says.

This ordeal will end.

“That is all I ask,” Belette says. “A kiss. After that you can have your dress.”

“I cannot believe a man who confesses to being a liar,” Cosette says. “I will scream, and other soldiers will come. You will be arrested.”

“The walls of the abbey are thick stone,” Belette says. “No one will hear.”

“Give me my dress,” Cosette says. “General Thibault will hear of this.”

“General Thibault is probably in London by now,” Belette says. “Dining at the royal palace. He cannot help you.”

“Captain Horloge then,” Cosette says.

“He is not here either,” Belette says with a snort that shows exactly what he thinks of Horloge.

“He will hear of it on my return to the abbey,” she says.

“So we have no agreement,” Belette says. “A shame.” He looks at the garment. “A poor dress for such a lovely girl. Just a rag really. And it will make a nice cloth for polishing my boots.”

He finds the seam at the hem of the dress and bunches the dress in both hands. He pulls and the seam gives way a few centimeters with a tearing sound.

“One last chance,” he says. “Or will I keep this rag and leave you to find your way back to the abbey clothed only in your own hands. A fine sight for the garrison, I would think.”

Do whatever you have to do.

“I will not,” Cosette says. Her eye falls on a large stone at the edge of the pool. She spins around and grabs it, turning back to see that Belette has moved even more quickly than she. His sword is drawn and pointed at her throat. She drops the stone and quickly regains what little modesty she can.

“Enough games,” Belette says. “You will now do exactly what I say. Firstly I want you to place both hands on top of your head.”

“I will not,” she says.

“If you do not move your hands, then I will remove them from your arms,” he says, laying the edge of the sword across her wrist.

“You are an evil man,” she says.

Survive.

He smiles. She spits at him. The smile drops and he raises the sword.

There is a swish followed by a dull thud. Belette looks down to see a metal bolt protruding diagonally from his chest.

Cosette screams and clamps both hands over her mouth to stifle the sound.

“That’s not right,” Belette says. He sounds dazed. His hand releases the sword, which clatters to the ground. “Mademoiselle, I would have done you no harm,” he says, but those are his last words. His eyes roll back in his head and he falls forward. Cosette has to jump out of the way. He lands at the edge of the pool, facedown in the water, his head slowly moving with the current.

Cosette screams again and snatches her torn dress out of his lifeless hand, holding it in front of her as she scans the forest.

A voice calls from the trees, “Please cover yourself, Cosette, so that I might come out.”

She knows this voice, although in her terror and horror she cannot place the owner of it.

“Stand where I can see you,” she calls back, still trying to arrange the dress in front of herself.

There is movement in the undergrowth.

François Lejeune emerges from the forest, fitting a bolt to a crossbow as he walks. He does not look in her direction, but only at what he is doing.

“François!” Cosette cries.

“Please cover yourself, Cosette,” François says.

Cosette takes her still-damp smalls from the rock and puts them on before donning the dress, also damp. It is hard to clothe herself with hands that shake like leaves, not only from the cold. The tear in her dress is unseemly but not immodest.

She says, “You killed him!”

“I killed a sinner,” François says. “An evil man who now descends to the place where he belongs.”

He moves to the body while still averting his eyes from Cosette. He pulls on the bolt. It is stuck and it takes an effort. As it comes free, a gush of blood runs from beneath the body, down into the pool, mixing with the water and fading from red to pink as it washes away down the stream. He cleans the bolt in the stream, then returns it to a clip at the front of the crossbow.

“I would say I am happy he is dead,” Cosette says. “But that would make me a sinner also, to rejoice in the death of another.”

“The only sins were his,” François says. “What he did, and what he planned to do.”

“Thank you, François, for saving me,” Cosette says. “I thought you were dead. I thought everybody from the village had been killed.”

“Most, not all,” François says. “Murdered by that devil Thibault. But I escaped. And so did many of the young children. I hid them in the church until the French soldiers left, then sent them to the church at La Hulpe.”

“You saved the children,” Cosette says slowly.

“As many as I could,” François says. “I wish I could have saved them all.”

“It is a miracle,” Cosette says. “It is a miracle that you are alive, and what you have done!” She hesitates. “What about Willem? His mother believes that he escaped also, and the French have questioned us about him, which gives us hope. Do you know anything of him?”

François smiles. “On that subject I can give you good news. There are tunnels beneath the forest, caves. Like a maze. The French do not know their way through. Not even I, who has spent my life in these woods, knows these tunnels, but Willem and Héloïse were able to use them to escape.”

“Where is he?” Cosette asks.

“I do not know that,” François says. “He vanished as only a magician can, right under the nose of the emperor.”

The shadows of the forest change as a cloud crosses the sun and a ravensaur calls high overhead. A breeze brings a deeper chill to her cold, damp skin, and she begins to shake again.

“You are certain that he is alive?” she asks.

“The French search everywhere for him,” François says. “Does that answer your question?”

Manners and reason desert her and she steps toward him, throwing her arms around his neck, pressing her face to his chest, relief escaping in gasping bursts. Immediately reason returns, and she pushes away.

He does not let go, and his arms wrap around her. They are large and strong from years of swinging the ax, and they are warm like hearthstones.

“You are as though made from ice,” he says. “Let me share my warmth with you for a moment. For the sake of your health.”

Cosette stops her resistance and melts into his body, happy that there is no one to see the impropriety except Belette, and his unmoving eyes see only the rocky floor of the pool.

No words are spoken, but they stay like that as the heat of his lifeblood seeps into her and gradually the shivering stops.

François endures the embrace for a moment longer, then gently pushes her away.

“Come with me,” he says. “I will take you away from here.”

“They will track us and find us,” Cosette says, wiping away tears.

“Pah! I know this forest better than a thousand French soldiers,” François says. “I roam as I please.”

She shakes her head. “Willem’s mother, Madame Verheyen, is imprisoned with me. I must return. If I escape, they will kill her.” She turns abruptly to look at the de

ad man by the spring. “But when Belette does not return…”

“I will dispose of the sinner’s body,” François says. “They will think he has fallen victim to a bear or a saur.”

“Still, I must go back,” Cosette says. “I will not endanger her life for mine.”

“Then I must rescue you both,” François says.

“This is not possible,” she says. “They will not allow both of us out of the abbey at the same time. And even if they did, they still hold Monsieur Verheyen. She will never leave without her husband.”

“I will find a way to rescue all three of you,” François says. “How often do you come here?”

“Every few days. As often as I can,” Cosette says.

“Look for me next time you come,” François says. “I will be here.”

“You are truly a miracle, sent by God,” Cosette says.

“I do God’s bidding, it is true,” François says. “Now go, before anyone else comes.”

Cosette touches his arm briefly, a more proper display of thanks and affection, before hurrying down the path back to the abbey.

Her heart and mind are conflicted. The relief of her rescue from Belette is tempered by her horror at the manner of his death.

But there are reasons for happiness also. François has survived, and thanks to him, so have many children from the village. She does not know who, but she sees faces. Pierre, the tailor’s son; Sylvie, the orphan girl; bubbly little Veronique.

These are small joys amid great sorrow, like diamonds sparkling on a black cloth.

There is one thing that bothers her. How had François just happened to arrive at exactly the right moment? She remembers the feeling of being watched as she walked to the spring. Was it François, not Belette? Surely that cannot be true. François is pious and proper. He averted his eyes when she was unclothed. It is unthinkable that he would have spied on her bathing. His fortuitous arrival must have been just a coincidence.

Later, when it is too late, something else will bother her, but it does not occur to her now. When she mentioned Willem’s father, François showed no surprise.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

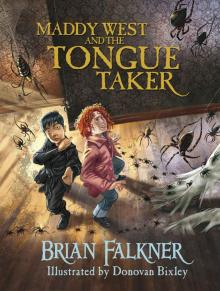

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker