- Home

- Brian Falkner

The Project Page 13

The Project Read online

Page 13

More tunnels led off in other directions as they reached a lower passageway, and doors were set into the sides of the main corridor.

It was an underground bunker.

The lair of the Werewolves.

27. THE DISCOVERY

“Do either of you have any idea what this is all about?” Ms. Sheck asked.

They were sitting on the hard concrete floor of a bunker cell, solid rusted metal bars preventing any thought of escape.

Tommy shook his head.

“I think I do. Bits of it anyway,” Luke said.

Jumbo’s bull-shaped head and thick neck appeared at the gate as he checked on them. Luke waited quietly for him to leave, looking around at the dank, dreary walls of the bunker.

So this was where Gerda had spent her childhood. Deep underground in a world made of concrete and brick, lit only by murky yellow electric globes, learning to hate the world that had trapped her here. Dreaming of a time when Nazi Germany would rise again and she would emerge into the sunshine, as one of the chosen ones. The golden children of the Third Reich.

Jumbo’s footsteps faded away down the corridor.

“I think Leonardo da Vinci made a really big discovery,” Luke said. “Something so incredibly powerful that he knew he needed to keep it supersecret.”

“Some new kind of weapon?” Tommy asked, but Luke shook his head.

“No, not a weapon. A …” He hesitated, trying to decide the right word. “A machine. I’ll get to that. I think Benfer somehow found out about Leonardo’s discovery. He must have found Leonardo’s drawings.”

“How is that possible?” Ms. Sheck asked.

“Beats me. Benfer grew up in Italy. Maybe he stumbled across another of Leonardo’s hidden laboratories,” Luke said.

“So what did he do with them?” Tommy raised an eyebrow.

“I think that when he realized what he had found, he knew, just like Leonardo, that this discovery would be really, really bad if it got out. It could never be made public. So he hid the drawings somewhere they would never be found. I think the book is some sort of treasure map. It tells you where to find Leonardo’s drawings.”

“Where?” Ms. Sheck asked.

“I have no idea,” Luke said. “I haven’t finished the book.” He shut his eyes for a moment. “There’s one clue that I think is important, but I haven’t been able to figure it out yet. A character in Benfer’s book: Johann Heidenberg. Benfer must have put him in the book for a reason. I was going to Google him or do some more research in the library, but we ended up here instead.”

“Did you say Johann Heidenberg?” Ms. Sheck asked.

“Yes,” Luke said, and spelled the name out.

A strange look came over her face. “I know that name,” she said. “He was a real person. We studied him in lit history at college. I remember him clearly; it was funny, because of his last name.”

“Funny ha-ha, or funny peculiar?” Tommy asked.

Ms. Sheck didn’t seem to hear him. “He lived in the late fifteenth century,” she said.

“Around the same time as Leonardo,” Luke said.

“Yes, probably,” Ms. Sheck said. “He changed his name to something else later, but I could only remember his original name, because of what he did.”

“What did he do?” Luke asked.

“He was German. He was an abbot who studied the occult—”

“Was Benfer into black magic?” Tommy interrupted, wide-eyed.

“Shut up and listen,” Luke said.

Ms. Sheck continued. “Heidenberg is most famous for a book called Steganographia, which is supposed to be about magic and dark spirits, but in reality it’s about secret codes and messages. All the secret code stuff is hidden inside the words of the book.”

“Are you sure about this?” Luke asked.

“Yes. Steganography means the art of hiding something in plain sight. Hiding information inside a message or a book. That’s why I always remembered his name. Johann Heidenberg. We called him Johann Hide-in-Book.”

“So that’s it,” Luke said. “That’s where Benfer hid the drawings. In the book! He must have destroyed Leonardo’s original plans but secretly put the information in Leonardo’s River.”

A door slammed somewhere in the depths of the bunker, a harsh metallic clang that reverberated off the hard rock walls of their prison. Luke jumped a little. The noise brought with it a cool fist of air. One of the lamps in the corridor flickered and dimmed for a moment with a sharp buzzing sound.

“Why?” Ms. Sheck asked. “Why keep the information at all if it was so dangerous?”

“I guess he couldn’t bring himself to destroy it,” Luke said. “I mean, this was the most amazing discovery in the history of science. Maybe he couldn’t bear to see it lost forever. But he made sure that the book was so boring, so mind-numbingly tedious, that nobody would ever read it.”

“Somehow the Nazis must have found out about Leonardo’s discovery,” Tommy said.

Ms. Sheck said, “The Nazis stole thousands of pieces of artwork, from many famous painters, including several of Leonardo’s pieces. They must have found their own copy of Leonardo’s drawings. Perhaps an incomplete copy, or an earlier copy.”

“Like a first draft,” Tommy said.

“Yeah.” Luke nodded. “They still needed Benfer’s book. That’s what Gerda said about ‘the last piece of the puzzle.’ They must have traced the other drawings somehow to Benfer and realized the truth about his book. But they were stuck. They couldn’t find the book, so they couldn’t complete their ‘great plan.’ ”

“Until now,” Ms. Sheck said.

“Until now,” Luke agreed.

“I still don’t get it,” Tommy said. “What was this fantastic discovery, this ‘machine,’ if it wasn’t some kind of super-weapon?”

Luke looked at them both, wondering if they would think he was nuts. Since he’d figured it out, even he thought he was going nuts. But it was the only thing that made sense, the only thing that connected all the dots.

“In the book there was this quotation,” Luke said. “I was just starting to read it when I fell asleep, and it didn’t really register at the time.”

“From Leonardo?” Tommy asked.

“Yeah,” Luke said. “He said, ‘In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes; so with present time.’ ”

Tommy nodded. “I remember that one from the book I read in the library.”

“But that’s not the whole quotation,” Luke said. “Benfer had the rest of it: ‘Were it possible to bend time upon itself, as a river twists and turns, then might not we journey across time as we now journey across a river?’ ”

Tommy looked confused, and Ms. Sheck looked horrified.

Luke said, “When Hitler talked about striking back at one minute past twelve, everyone thought he meant at the very last minute. But what I think he really meant was from another time!”

“Another time?” Ms. Sheck was incredulous.

“It’s something to do with the rare-earth magnets,” Luke said. “Some way of bending time. The drawings of the Vitruvian Man are a blueprint. A diagram of how to do it.”

“That nude dude in a circle is a blueprint?” Tommy said skeptically.

“It’s not just a circle,” Luke said. “There is a whole series of drawings, remember. When you put them all together, it’s a nude dude in a cube. And a sphere.”

“A diagram of a time machine,” Ms. Sheck said.

“But why does …” Tommy trailed off as he caught on to what Ms. Sheck and Luke had already realized.

Mueller didn’t have an atomic bomb. He didn’t need one. All he needed were the plans.

Mueller was not planning to destroy the world.

He was going to change the course of history.

“Oh, crap,” Luke said. “Do you remember when Mueller and Gerda said ‘in a few days none of this will matter at all’? I couldn’t understand what

they could do in just a few days. There’s only one explanation. It wasn’t a copy of Leonardo’s drawings that the Nazis discovered; they must have found his time machine itself.”

“In Italy?” Tommy asked.

“I guess. They probably packed it up and shipped it here to the bunkers, piece by piece.”

“You mean they’ve already got the time machine?” Tommy’s eyes were saucers.

“I think so,” Luke breathed. “But they didn’t know how to use it. It wasn’t a set of plans they needed. It was an instruction manual.”

“And now they’ve got one,” Ms. Sheck said.

28. PRINCESS

“You know how Leonardo invented all those crazy things, like submarines and helicopters and hang gliders?” Tommy said, and Luke looked over at him, guessing what he was going to say next. “I’ve just been thinking that maybe he didn’t invent them at all. Maybe he saw them.”

“You mean he traveled to the future?” Ms. Sheck said.

“Yeah.”

Luke nodded; he’d been thinking exactly the same thing. “He saw some of these things and went back and tried to design them, but using fifteenth-century technology.”

There were murmuring voices and footsteps in the corridor outside their cell. Luke glanced up to see Mueller and Mumbo walk past the barred gate.

Each of them wore the black uniform of a 1940s German SS officer.

“They’re getting ready to leave,” Luke said.

On a trip like no other, he thought. A journey back to World War II.

“We’ve got to stop them,” Ms. Sheck said.

“How?” Luke asked, looking at the thick bars of the gate.

“I don’t know how, but we have to. The Nazis came very close to inventing an atomic bomb in the 1940s,” Ms. Sheck said. “With Mueller’s plans, they will succeed, and they will win the war.”

“We’ll be Nazis,” Tommy said glumly.

“I don’t think so,” Luke said. “I don’t think we’ll exist.”

Tommy looked up sharply.

“Well,” Luke said, “if you change history that much, you’ll change everything. Your grandparents might never meet. Your parents won’t be born. So you will never be born. Same for everyone else we know. It’ll be a completely different world, with different people in it.”

Luke examined the gate again. Surely there had to be some way to get out. But it looked solid, if brown and rusted, and it still looked just as locked. It was secured with a heavy-duty modern brass padlock.

Maybe with Tommy’s lock pick they might have had a chance, but that was in his backpack. And the Werewolves had that.

“If we could get out of here,” Luke asked Ms. Sheck, “what would we do?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “But if they get back to the 1940s with those plans, then that’s the end of everything.”

As Luke was standing at the door, Jumbo limped past, also in the uniform of the SS. He scowled at them.

Luke scowled back. Mean faces weren’t going to scare him. Hitler with a nuclear bomb … that scared him.

He tried to shake the bars but they didn’t move. He scanned around the tiny cell for anything that they could use to lever them apart, but there was nothing.

When Luke turned back toward the front of the cell, Gerda was there, watching him, the pistol in her hand.

“What are you going to do?” Luke asked in an unsteady voice.

She glanced down absently at the pistol. “Oh, don’t be afraid,” she said. “I’m not going to hurt you. Erich and the boys are getting ready to go, and he wants me to keep an eye on you to make sure that you stay exactly where you are.”

They weren’t going anywhere, Luke thought, but he said nothing.

After a while, Mueller appeared with a wooden chair and placed it for her a few feet back from the cell.

“Thank you, Erich,” Gerda said, taking the seat and resting the pistol on her knee.

“We are about to depart,” Mueller said. “I will see you in the New World.”

A glow seemed to come over Gerda and her eyes glazed. Luke sensed her mind was elsewhere—daydreaming about a different life, perhaps. One of glittering riches and fancy parties with handsome young men. “Auf wiedersehen, Erich,” she said, almost in a trance.

“Heil Hitler!” He snapped out a Nazi salute.

She returned it with a tired lift of her arm and then stood. They embraced for a short moment.

Mueller turned, his heels clicking together, and marched back down the corridor.

Heading for the past. For his new future.

Luke watched him go.

“Gerda,” he said softly after a while, and she looked up. “Are you really going to let him do this?”

“We have been planning this all of our lives,” she said. “Since decades before you were born. We have waited a long time for this moment.”

She looked down, and the pain and the strain of those years of hiding, living underground, showed clearly on her face.

Ms. Sheck stood and moved beside Luke. She said, “You know what will happen if Hitler gets the atomic bomb, don’t you?”

Gerda said nothing.

“Millions will die,” Ms. Sheck said. “Hitler will use the bomb indiscriminately. On London, maybe. Or Washington. Moscow probably, the first one. The United States will retaliate with its own atomic bombs. Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich will cease to exist.”

Gerda said nothing, but somehow she looked older and frailer than before.

“Hitler will use the bombs without mercy,” Ms. Sheck said. “He murdered millions of innocent Jews in the concentration camps and—”

“That’s a lie,” Gerda snapped, her eyes burning at Ms. Sheck. “That is propaganda made up by the Allies after the war to try and make us out to be evil monsters.”

“It is no lie,” Ms. Sheck said. “There are thousands of photos of those camps, and evidence of what went on there.”

“All created by the Allies,” Gerda said.

“All of it true,” Ms. Sheck said. “I wish it wasn’t. My grandfather survived one of those camps. His mother and father, his brothers and sisters did not.”

Gerda looked away, no longer wanting to meet Ms. Sheck’s eyes.

“I will be a princess,” she whispered, her eyes faraway.

“You are condemning me to death,” Luke said. “Me and Tommy and billions of other kids all over the world.”

“You will never have existed,” Gerda said. “That’s not the same as being killed.”

“It is from where I stand,” Luke said.

“I will be a princess,” she said again, and rose a little unsteadily.

“In a nuclear wasteland!” Luke shouted in frustration as she tottered away down the long corridor.

He left the gate and sank back down against the wall of the cell, close to despair. He had the feeling that at any moment he would just vanish. Dissolve into nothing, as Mueller and his cohorts changed the past. Changed his past.

If by some miracle he did still exist, if his grandparents did still meet, and his father still met his mother, would he be the same person he was now?

Most likely I would be a Nazi, Luke thought. Everyone would be Nazis. He stood, walking around the cell one more time.

Tommy stared at the floor. Ms. Sheck smiled at him, but there was no trace of hope in it.

He looked at the bars again. Back on the farm, his dad had often told him there was no problem in the world that couldn’t be solved with a little hard work and common sense. But then, his dad had never been stuck in a Nazi prison cell waiting for the world to end.

He forced himself to focus. The cell’s left and back walls were rock, as were the floor and ceiling. Given the right tools and enough time, they might have been able to tunnel out, but they had neither tools nor time. The right wall was made of solid concrete blocks.

If he could take the pins out of the hinges, he could open the door that way. But the hinges were welded over top and bo

ttom to prevent exactly that.

All the bars were rusty, though, and the hinges had creaked when they had been forced into the cell. Rusty metal meant weakened metal, but nothing looked weak enough to help them.

He moved along the bars, shaking each one in turn, hoping for one that was loose, but they all held firm.

Okay. What was the weakest point? The bars connected to a long horizontal metal crosspiece at the top and another at the bottom. Two more such crosspieces ran through the middle of the bars, preventing any chance of bending them.

There was no room above or below the bars to squeeze through. Nor on the sides. He rattled the door in its frame and was rewarded by nothing more than a few flakes of rust falling.

Luke moved over to his right, examining the concrete blocks at the end of the wall. One of them didn’t look as straight as the others. He pushed on it, but it didn’t move. He grasped it by the end, putting his hands through the bars of the cell to do so, and yanked it toward him with all of his strength.

To his surprise, it moved, not even an inch, but it moved. It was loose.

He looked over at the others. “Give me a hand,” he said.

“What?” Tommy jumped up, filled with renewed hope that Luke thought was somewhat premature.

“Push on the other end of this block,” Luke said. “As hard as you can.”

Tommy flattened his hands on the block and shoved. Luke pulled again on the other end, and with a grinding noise, the block shifted. Crumbling sixty-year-old mortar fell out of the gaps between the blocks.

“Again,” Luke said.

They shoved again and the block moved more. Gradually, by pulling and shoving, they were able to maneuver the block out of position and slide it forward until it dropped to the ground outside the cell, leaving a small hole in the wall.

Luke froze. “Do you think they heard that?”

There were no sounds from the corridors, and after a moment he turned his attention back to the wall.

The block above the hole was now being held by just a thin strip of mortar.

Luke climbed up on the bars of the cell until he could touch the ceiling and kicked at the block. Two or three good kicks and it fell down onto the block below it, disappearing behind the wall.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

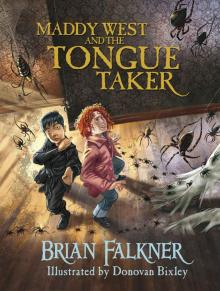

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker