- Home

- Brian Falkner

The Tomorrow Code Page 18

The Tomorrow Code Read online

Page 18

“She’s got character.” Rebecca smiled. “I’ll name her for you.” She thought for a moment. “Z-two, zeto…”

“Zeta,” supplied Tane.

Rebecca looked at him for a moment, before accepting it.

“Zeta,” she said. “Hi, Zeta!”

Zeta looked over at her and held out a hand as if she would like to jump onto Rebecca, but the Texan held the animal firmly.

Crowe did not find it funny. “They’re not pets,” he repeated.

“Makes it harder to stick electrodes in their brains and vivisect them, doesn’t it,” Rebecca said with a little-girl innocence completely at odds with her words. “How about the other one, Z-one?”

“Xena,” suggested Tane.

“Zeta and Xena,” Rebecca declared. “And what little test have we got lined up for you today, Zeta?” She held out a hand to Zeta, who patted it and looked up at her with big, sad clown eyes.

“We’re going to put her in the tank,” Crowe said flatly, to Rebecca’s look of horror.

The end of the tank was a separate box, sealed off from the rest of the tank by a glass door with thick rubber seals.

They let Zeta climb in the box, which she did willingly, trustingly, and then sealed the lid above her. In the main compartment of the tank, there were whistling, swishing noises as the jellyfish, agitated, swept around in circles in the mist.

Zeta jumped a little and turned around and around inside the small area, but otherwise didn’t seem too concerned about being shut in a glass box.

“You can’t!” Rebecca said, again and again. “You can’t put her in the tank with that thing!”

Southwell, looking quite uncomfortable, tried to explain. “She’ll give us very valuable data. Chimps are our closest cousins.”

Manderson contributed, “Genetically, they are ninety-nine percent the same as humans.”

“Don’t flatter yourself,” Rebecca muttered, but the insult went straight over Manderson’s curly head.

Crowe said, “We need to know what these pathogens can do to us.”

“And you need to sacrifice an innocent animal to find out?”

“It’s just one chimp,” Crowe said with a look of annoyance. “Fifty thousand human beings got ‘sacrificed’ in Whangarei. And there’ll be more if we can’t figure out what is going on.”

With a nod from Crowe, Manderson released the seals and Zeta’s compartment flooded with the fog.

“No!” shrieked Rebecca. She pressed her fingers against the glass by Zeta’s head. Zeta looked at her and gave her a big clown smile. The other USABRF men gathered around to watch.

Zeta seemed bemused by the fog at first, as it started to fill her chamber, then a little confused as it thickened around her. The jellyfish whistled around in the thick of the fog, avoiding the thin vapor at the other end.

“They can’t exist outside of the fog,” Crowe murmured, watching intently. “They can’t move, they can’t live. It’s their nutrition and their locomotion.”

One jellyfish flashed down the side of the tank near them. By now the fog had spread evenly between the two partitions. The jellyfish whirled around Zeta, then disappeared back into the fog.

That was all. Nothing else happened.

After a while, Zeta went for a walk. Tane held his breath and could hear from the sharp intake of air from Rebecca that she was doing the same.

Zeta wandered through the main tank, comically trying to wave the fog away from in front of her eyes. She found one of the jellyfish, drifting at about her eye level, and Tane winced as she stretched out a hand toward it.

The jellyfish remained motionless. She even batted at it with her hand, swatting it like a fly, but without effect.

“It’s not interested in her,” Southwell said with a puzzled look.

“Okay, that’s long enough,” Crowe said.

“Go, Zeta!” Rebecca yelled in a mixture of delight and relief, hopping from one leg to the other and punching the air. “You go, girl!”

Zeta screeched and danced happily inside the cage, a little two-legged, two-armed Irish jig. Tane and Fatboy laughed, but Crowe just shook his head.

They reversed the procedure with the small compartment at the end of the tank, sealing off the main section before pumping in air and extracting the fog.

“Are you going to let her out?” Rebecca asked.

“She may be contaminated,” Crowe replied, then, a little too quickly, said, “Dr. Southwell, would you show them the journals?”

Southwell led them to the far side of the room, where a series of notebooks were spread out on a table.

“Professor Green’s notes,” she said. “Do you know much about what they were researching?”

“Tell me,” Rebecca said. “Vicky told us it was rhinoviruses.”

“Actually, it was rhinoviruses they were researching. They did a small amount of work on NLVs, but only for a short time, to confirm some aspect of their main research. They were researching conserved antigens. That’s common structures within the viruses that can—”

“She told us about that too,” Rebecca interrupted. “How much do you know about the Chimera Project?”

Southwell said, “Conserved antigens proved to be elusive. Our immune systems just kept getting fooled by the changing shapes of the viruses. It was a dead end.”

“So?”

“Professor Green recently gained health department approval to experiment on the other side of the equation.”

“The human side of the equation?”

“Yes. They were playing around with bone marrow, where antibodies are produced, genetically engineering our immune systems to try to produce a generic antibody.”

“An antibody that would recognize any kind of virus.”

“Any kind of rhinovirus. That was the field they were concentrating on.”

“And how,” Rebecca asked, a little skeptically, “do you start to create a generic antibody?”

“The scope of the project approval was quite specific. They were genetically splicing together different kinds of antibodies, creating a…” She trailed off, seemingly unwilling to finish the sentence.

“A chimera.” Rebecca finished it for her. “Is that it? Is there anything else you can tell me?”

Southwell shook her head. “Nothing. Professor Green had not yet submitted a report on the results of the research. All we have is her notes.” She indicated the table again. “Would you mind having a look through? Tell us if anything sticks out.”

“Of course,” Rebecca said, and picked up the first journal.

Tane idly leafed through one. Rebecca was the only one with a hope of understanding them, but it was interesting to see the clearly handwritten notes, dates, and formulas that the late Professor Green had written. Vicky’s handwriting was small, neat and verbose, flowing on, page after page. Tane idly wondered why she hadn’t just typed up her notes on a computer.

Fatboy was the first to notice, glancing across at the other side of the room. “What are they doing?” he wondered.

Tane looked across, and Rebecca also. Two of the men had their hands in the gloves in the sides of the compartment. One was holding Zeta while the other ran a needle into her arm.

Zeta didn’t like it; she screeched and snarled at the men.

“They’ll be taking a blood sample,” Rebecca said. “To see if the fog had any effect on her.”

She looked back at the journal she was reading, only to look up again a second later to check on Zeta.

The man with the syringe had withdrawn it, but it was empty. With a frown, Rebecca walked across the room to the tank. Zeta looked sadly, imploringly, at her from inside the glass.

“What are you doing?” she asked. “You’re taking a blood sample, right?”

Crowe was there now. “Miss Richards, this is our work. I’d like you to let us get on with it.”

“That was a blood sample, right?”

Inside the tank, Zeta began to shiver. She sat d

own suddenly and looked up at Rebecca like a frightened child. The top lip of her clownish mouth drew up into a sneer.

Southwell put her arm around Rebecca’s shoulders and tried to steer her away. She shook the arm away violently.

“What have you done to her?”

Zeta slumped against the side of the tank, her eyes open. Her breathing was ragged, heavy. She looked up at Rebecca one last time; then her eyes just glazed over and remained open. Her chest was still.

Crowe took Rebecca’s arm this time, firmly, and drew her away from the tank.

Rebecca cried, “You killed her! What are you going to do, dissect her to see if the fog has affected her?”

Crowe said nothing.

“You are! You monsters!”

“Monsters?” Crowe hissed, the stony façade cracking for the first time. “Monsters!” He grabbed Rebecca by the back of the neck and pressed her face against the glass of the large tank. There was a whistle and a flash of white fog, and two of the jellyfish smashed into the glass, just a few thin fractions of an inch away from her eyes and mouth. She screamed. Tane jumped forward, and Fatboy was with him, but strong arms gripped their elbows, pinning them.

“There are your monsters! We don’t have time to wait and see how the animal is feeling in a month or so. We have just a few days before the fog hits Auckland. We need answers right now!”

“Murderer!” Rebecca whispered, sobbing, her lips crushed against the glass.

Manderson reached in with the rubber gloves and laid the body of the chimpanzee flat on the floor of the tank. In death, Zeta had found peace once again. The forced sneer was gone, and her face held its natural sad-clown expression.

Crowe looked at Rebecca with stony eyes. “I told you not to give it a name,” he said.

XENA

Rebecca could move pretty quickly when she wanted to. The soldiers should have known that already. But they were all gathered around the tank.

Rebecca was at the cage, unsnicking the lock, and Z1—Xena—was in her arms before anybody realized what she was doing.

“Put the animal down,” Crowe ordered, and he was clearly a man who was used to being obeyed.

Rebecca was a girl who was used to disobeying. “You’ve murdered one innocent creature today; you’re not getting this one too.”

Crowe moved toward her. Manderson and another soldier, Crawford, according to a badge on his helmet, moved slowly in behind her. She edged to her side. “Leave us alone!” she yelled.

“Leave her alone,” Southwell said. “Let her calm down.”

Crowe almost looked as if he were considering that for a moment, then he said, “No, we don’t have the time. I had hoped that they might be useful in understanding Professor Green’s work, but so far they’ve been just an obstruction.”

He spoke to Crawford, behind Rebecca. “Take the animal off her and get all three of them back to Auckland.” He turned to Southwell. “Get them charged with trespass or…something…so your police can keep them out of our hair.”

Crawford nodded and circled around Rebecca to grab Xena. Manderson gripped her shoulders from behind, despite her shaking and struggling. Crawford put his hands under Xena’s arms and began to pull. Rebecca held on tightly, and the chimpanzee, sensing the struggle, hugged her tightly back. Crawford was just trying to pry Rebecca’s hands from around the chimp’s back when Tane hit him broadside.

Fatboy had played rugby league in school and had a pretty tough reputation from years of tackling huge front-row forwards. Tane had never played rugby in his life. But he’d been to plenty of games to watch his brother play, and he hit Crawford in a textbook midriff tackle.

It cut him in half, knocking him to the floor and sliding both of them across the room toward the tables holding the tank. Crawford’s back hit one of the table legs and the whole structure shuddered.

“Look out!” Crowe yelled.

Manderson, with incredible reactions and speed for a big man, was at the side of the tank before there was any danger of it falling, steadying it with two hands.

Crawford leaped up and angrily hauled Tane to his feet, his arm swinging back in a fist. Tane, facing the side of the tank, brought his hands up to protect himself and had just enough time to wonder, Where are the jellyfish? when Southwell said, “Something’s happened in the fog tank, Stony.”

Crawford’s arm remained tense but his eyes were on the tank. Everybody’s eyes were on the tank.

The fog was swirling. Not just quivering a little from the knock to the table leg, but twirling and swirling in broad patterns inside the tank.

“Where are the jellyfish?” Manderson asked in his slow Texan drawl, echoing Tane’s thoughts. His hands were on the glass sides of the tank, but the jellyfish had not attacked.

A young-looking soldier, whose name badge read EVANS, said from the other side of the tank, “There’s something new forming over here.”

The chimpanzee was forgotten, Rebecca was forgotten, and Tane was forgotten. Crawford’s arm dropped as the men crowded around the tank.

Tane moved to where he could see. It was a larger object, not really a definable shape at all, just a mass of a white substance, more visceral than the jellyfish, with a moist, diaphanous surface, like that of a slug.

“The fog is thinning,” Crowe noted. “It is being formed out of the fog.”

Tane watched as the shape grew a fraction of an inch or two in diameter in front of his eyes.

“Why now?” Crowe asked, as if he had been expecting this to happen sooner or later.

“The knock to the tank?” Crawford asked.

“No. Look at the size of it. It’s been forming for quite a while,” Manderson pointed out.

They all watched in silence for a few moments, but the shape grew no farther.

“It’s run out of fog,” Crowe decided after a while. “It needs more fog to grow. But why suddenly now? What has happened to trigger that growth?”

He sounded concerned.

“Do you want to run the same tests?” Crawford asked, glancing at Rebecca and Xena. Rebecca recoiled, taking a few steps backward and twisting Xena around behind her as if to protect her.

“I don’t know,” Crowe murmured, not taking his eyes off the glutinous shape. “Start with the human cell tests.”

Rebecca was ignored and drew closer to the tank again, intrigued, as two of the soldiers put their hands in the thick rubber gloves on the side of the tank. The big white slug quivered, but did not move.

A small petri dish was introduced through an air lock at the end of the tank, and one of the soldiers opened it carefully inside.

The fog was a lot thinner now, and it was easier to see what was going on. Inside the petri dish were a few small objects that took Tane a moment or two to recognize. There were a few hairs, human he realized, and some nail clippings. Evans picked up a hair out of the dish and dropped it carefully onto the white shape.

It touched the surface of the blob and just disappeared. At first Tane thought it had sunk into the material, but then he realized that it hadn’t. It had just “melted” on the surface.

The fingernail clippings followed, with exactly the same effect.

“Test the pH,” Crowe said.

Evans tore open the plastic seal on a small cardboard strip already placed inside the tank and touched it to the surface of the object. After a moment he said, “Neutral. Just slightly alkaline.”

“So it’s not an acid,” Crowe said, deep in thought. “But it dissolves human cells.”

“Like butter on a hot griddle,” Manderson drawled.

Rebecca, Tane, and Fatboy might as well have been invisible, so little attention was paid to them.

The soldier-scientists spent the next hour running batteries of tests on the small white blob, but always, Tane thought, with inconclusive results. At least that was the impression he got from their expressions as they discussed, in highly scientific terms, the results of each test.

One thing was c

lear to Tane, though. This substance, whatever it was, was related to the disappearance of all those people on Motukiekie and Whangarei.

A fax machine set up on a table in a corner rang while the tests were going on, and Southwell went to check it. She came back with a concerned look on her face.

“Stony,” she said, “the fog is moving much faster than we thought.”

Crowe looked at the printout, a detailed weather satellite image of the area. His eyes opened wide. “Warkworth! We hadn’t expected it to get that far south for another couple of days. It’s accelerating! At this rate, it’ll be here by tomorrow.”

“Let’s hope it doesn’t get any faster,” Manderson said slowly.

Tane, Rebecca, and Fatboy looked at each other in alarm.

“Had they completed the evacuation?” Crowe asked.

Southwell said, “Yes. Orewa also, and they’re starting to evacuate Torbay, Albany, Greenhithe, and Helensville.”

Those three towns represented the northernmost tip of Auckland. The fog was getting close to the homes of a million people.

“When were these taken?” Crowe asked, scanning the image for a date and time.

“This morning at first light.”

“First light! Get back to the meteorological people. I need to know how far south it’s come since then.” He spun around to Manderson. “Where are the SAS and NZ Army units?”

“Base camp. Silverdale. Just down the road.”

“Pull them back to Albany. We’ll never have time to set up the defensive line at Waiwera before it gets there.”

He looked back at the tank. “Damn! I was hoping for much more time than this. Get the equipment packed up, and get the men ready to evac. That fog is just up the road and heading this way. I don’t want to still be standing around, running tests, when it gets here.”

There was a flurry of activity as the soldiers worked to pack up their equipment, disappearing, probably down to the big black trailer units that Tane had seen parked outside.

Only the main tank remained, and some odds and ends of equipment, lined up by the door, when Crowe looked across at Xena, still perched in Rebecca’s arms. Rebecca was sitting on a chair on the far side of the room having a long conversation with the chimp about the Möbius submarine. Xena seemed interested, interjecting occasionally with screeches and sudden gestures of her own. At one point, she started looking through Rebecca’s hair, apparently looking for nits, but (fortunately) didn’t find any.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

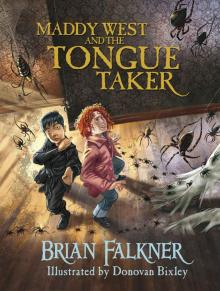

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker