- Home

- Brian Falkner

The Flea Thing Page 2

The Flea Thing Read online

Page 2

Frank was putting the squad through some rigorous exercises when we arrived. There were jumps and press-ups and lots and lots and lots of wind sprints. To be honest, I didn’t actually know they were called wind sprints until later. It was something that Frank had picked up from a season he had spent in the United States with a Grid Iron coach.

It all looked very difficult, and the tackling exercises looked really gruesome.

‘He gobbled the dirt like a bobcat,’ Jason said, after one player ended up face down on the field after a particularly hard tackle. Jason was like that. He had his own language. He would never say something was ‘funny’. He’d say it was ‘funny as a monkey in a three-piece suit’. As far as I knew he just made the stuff up, but he always seemed to have a phrase ready at hand.

We noticed that Ricky ‘Road Runner’ Albany avoided a lot of the tackling exercises. He seemed to see himself as being above all that and, I suppose, in a way he was. He was a flying winger, not a front row forward. It didn’t please Frank very much, that was obvious, and a couple of times he had to bawl Ricky out to get involved.

‘He’s lazy,’ said Jason, watching with me from the sidelines.

‘He’s a winger,’ I said. ‘He can’t afford to get injured in training.’

‘I couldn’t give the liver of a two-ton goose,’ said Jason. ‘He’s lazy and a scaredy-chicken.’

Henry Knight ran over near the fence we were leaning against. He started doing some stretching exercises. He was the biggest player on the team. Up close he looked three times as large as he did on the TV. If his skin had been green he would have looked like the Incredible Hulk. Henry smiled at us.

‘Hi, guys. You here to watch the training?’

Jason said, ‘No, we’re …’ but I cut him off.

‘Sort of,’ I said, not wanting to give too much away.

‘Well, enjoy yourselves,’ Henry said. ‘We’ve got a new player coming in today to try out.’

Jason blurted out before I could stop him, ‘That’s him. Daniel.’

Henry stopped stretching for a moment and looked down at me from a towering height. He seemed to grow bigger as he looked, or was I suddenly shrinking? I felt about as big as a flea. Which was kind of a funny thought, ’cos nobody actually called me that till much later.

Henry said, ‘No, I mean for the first graders.’

‘Yeah, ya snot-gropper, it’s Daniel.’ Jason insisted. I kicked him, which must have hurt with the boots on, but he didn’t show it. Henry laughed, a huge eruption that rumbled out from somewhere deep in the mountain that he was.

‘Good on you, kid, good one.’

‘It’s true,’ I said quietly, a little bit peeved, although I knew I shouldn’t be.

There was a ‘hoy’ from behind him. Henry stopped laughing and looked around at Frank, who was waving his arm. ‘Hoy, Daniel.’

Jason told me later that the look on Henry’s face when I swung my legs over the fence and trotted over towards Frank was like he’d just been smacked in the face with a raw albatross.

‘Team, I’d like you to meet Daniel,’ Frank said in a big grizzly bear voice that stopped talking right across the field. Even Ricky, who was complaining to one of the trainers about something, shut up immediately. ‘Daniel is twelve. He’s here to try out for the first grade squad.’

There was laughter from everybody, except for Henry, who knew a little more than the rest. Frank spoke again and the laughter stopped immediately.

‘I’m not kidding. This week Daniel earned the right to try out for the team. Don’t ask me how. It’s highly unusual, but he’s here, he means business, and I think we need to give Daniel the respect that he deserves.’

Ricky had been wandering over towards me while the coach had been talking. He stepped up to me and put out his hand. I shook it, a little bit nervously.

‘Welcome, Daniel,’ Ricky said with a sincere smile. ‘I hope you do well.’

‘Thanks.’ It was hard not to be overawed in the presence of all the players I had watched so often on the television. Henry tousled my hair from behind. From anyone else, I would have been annoyed. It was the sort of thing you do to a child, not a twelve-year-old. But Henry seemed to treat everyone that way. In a way, I supposed, when you are that big, everyone else would seem like a kid.

Frank said, ‘Daniel, this is a first for me. It’s a first for all of us. We’ve never had a twelve-year-old try out before. I’m not sure what to do.’

I was quite sure what to do, but I didn’t want to say so. Not just yet. So I said, ‘I’ll be thirteen before the season starts.’

‘Yeah, coach,’ said Ainsley, the little five-eighth. ‘Get it right.’

There was laughter from around the field, but that was exactly what I had wanted.

‘I’ll make a bet with you, Mr Rickman,’ I announced loudly, using the coach’s surname deliberately.

Frank groaned. ‘Not again!’

‘Give me the ball. I’ll go down that end. You put your best tacklers on the field. If I can make it to the other end and score a try, I get a place in the squad. That’s all.’

There were claps and cheers from the players, but Frank looked serious. ‘That’s a big call,’ he said, no doubt thinking about the pencil sharpener and the coin. ‘You have surprised me before.’

I snapped shut the trap I had been preparing with an almost audible clang.

‘Are you saying that the best tacklers, in the best rugby league team in the country, can’t stop a twelve-year-old boy from scoring a try?’

The claps and cheers were louder this time. ‘Yeah, Mr Rickman,’ someone called out from the back.

‘My best tacklers,’ Frank said at last.

‘That’s right,’ I said, more confidently than I felt. ‘Your best defence.’

‘All right, you’ve got a deal, unless anyone objects?’ Nobody did. Frank reached down and shook my hand. ‘That’s what we call a Gentleman’s Agreement. Sealed with a handshake. But I’ve got to be honest with you, Daniel. They’re all my best tacklers! Get out there chaps. All of you.’

Frank tossed me a ball. The players, thirty or so in number, began to move around on the field. I, however, stood my ground.

‘That’s not fair. There are only thirteen players in a side. You can’t put the whole squad out there, reserves and all. That’s more than you’d ask of anyone trying out.’

‘You’re right, kid,’ Frank said, and I noted that it was the first time he had called me ‘kid’. It wasn’t to be the last. ‘But you’re not just anyone. You’re twelve, nearly thirteen, and if you were somehow to succeed in this, my neck would be on the block. These are not kids’ games here. This is serious, professional rugby league and there’s a lot of money at stake.’

He called out to the other players, spreading themselves out into a defensive pattern on the field.

‘Understand this, chaps. We can only have so many players in the squad. If Daniel scores his try, then one of you will have to be dropped to make room for him. I know he’s just a kid, but he’s fast. Faster than you are going to believe. So take this try-out seriously. Standard sliding defence. Reserves form a second defensive line behind the run-on players. Anybody not understand me?’ A chorus of grunts showed that the jovial attitude was now subdued, just a bit.

‘Daniel, do your best. But remember these are top, professional players. They tackle fast and they tackle hard. They will try not to hurt you, but they will stop you. Believe me. They will stop you.’

And that was the end of the speech. But, like a lot of endings, it was really the beginning of something else. Something else indeed.

FOUR

THE THING

From the far end of the football field the opposition goal line looked a long way away. Further than it looked when we played junior grade games at Glenfield Park. Still, I reminded myself, it was the same game. True they were bigger, a lot bigger. True, they were faster, and more skilled. But, I told myself over and over again, the

y were about to get the shock of their lives.

The grass was greener than at most of the grounds I played on. Better looked after, no doubt. The goalposts were higher too. We were on the second grade field, adjacent to the main stadium, but it still seemed a world away from Glenfield Park.

The top players in the squad formed an impenetrable wall that looked as high as a tree and as solid as concrete. Behind them, should I make it that far, was another wall, just as big, just as hard.

I tucked the ball under my arm and began to run. I weaved a little, angling back and forth as I approached ‘the wall’, probing for weaknesses: a lazy player; half a gap. There were none. I ran up almost within arm’s reach of the wall, and as they moved forward to tackle me, I circled away from them, back towards my own goal line. They didn’t follow me, preferring to keep their line intact.

I darted towards the left side of the field, away from the wing of the speedster, Ricky. The sliding defence slid across with me, a solid wall of jerseys. I circled away again.

Then I did the Thing. I blinked. Twice.

It was the Thing I had done in Frank’s office. The Thing I did when my side was losing and needed to score. The Thing that I had been able to do ever since I could remember. In fact it had taken me quite a few years to realise that other people could not do the Thing. So I kept it quiet. Jason knew about it. My parents sort of knew about it, but didn’t understand it and preferred not to talk about it. Jenny, my girlfriend, thought she knew about it, but she only knew half of it and that was all she was ever going to know. And she wasn’t even my girlfriend, really.

Blinking twice wasn’t the Thing. I don’t even know why I blinked. I couldn’t help it, it just happened when I did the Thing. I blinked twice as I did the Thing and the world turned into slow motion. Slooowwww mooottttiiionnnn. Like on the action replays on the television when the video ref is trying to work out if a player actually grounded the ball. Everything went into slow motion, except for me. I was still on normal play.

That was how I had got the pencil sharpener and the coin. If I did the Thing and then moved as fast as I could, it was so fast in the ‘real world’ that I was just a blur.

I ran towards Ricky’s wing. I ran, but not too fast, a sort of leisurely run. If I ran as fast as I could it would look strange, like I had almost disappeared, and I didn’t want to give the game away. Give my Thing away.

The Warriors’ heads turned in slow motion to watch me as I streaked (in their eyes) towards the wing. Ricky was already moving to intercept me and the other players were trying to close up gaps as quickly as they could. A couple of metres from the line I stepped off my right boot and changed direction suddenly towards the left. The team were still sliding to the right as I tucked through half a gap that had appeared beside Henry, who hadn’t managed to slide across as quickly as the rest.

It was as easy as that. ‘I’m in the team!’ I thought to myself, although I knew I wasn’t there yet. I still had the second line of defence to beat. And, as so often happens, that one, quick thought, that one tiny lapse of concentration, turned out to be a big, bad mistake.

I ran a few paces towards the second line then changed course again. I changed course right into Brad Smith, who, to be honest, was doing little more than standing there wondering what the heck was going on. Brad had rushed up out of the second line, hoping to strengthen the first line. It wasn’t the smartest thing to do, in fact it went against everything they trained for. But Brad wasn’t the smartest, or the best player on the team, and that’s what he did.

He shouldn’t have been there, but he was. I should have been looking, but my eyes were in the other direction and my mind, for just a second, was on my wonderful victory-to-be. And so I ran straight into Brad. I bounced off – naturally – and ended up flat on my backside on the ground.

The ball popped up out of my arms in the collision. Brad snatched at it, missed, and knocked it straight into the arms of the fastest Warrior of all time, Ricky ‘Road Runner’ Albany. Ricky did what any highly trained, professional rugby league player would do. He did it instinctively. He grabbed the ball in both hands and headed for the try line. My try line!

‘Score!’ shouted out from half a dozen places in the team, and Ricky was well on his way to doing just that. Henry wasn’t looking at Ricky. He was looking at me and his eyes were soft and sad.

Brad was looking at Ricky, and he would swear afterwards that he could not understand what happened next. Neither could Ricky, but that’s a different story.

Ricky had started from nearly halfway, and he was only a couple of metres or so from the try line when I recovered enough from the bump to work out what was going on. At first I wanted to cry, but at twelve, nearly thirteen, you are far too old to cry. Then I caught a glimpse of Jason’s face on the sideline.

It was funny. There I was, sitting in the middle of the paddock with the fastest Warrior alive about to score a try against me. I had missed out on the Warriors’ squad, and Jason was smiling. He wasn’t smiling because it was funny, or because he was laughing at me. Jason wasn’t like that. He was smiling because he still believed that I could do it.

That’s what got me back to my feet. That’s what got me running, sprinting. That’s how I reached Ricky even as he was diving over the line for the try.

I punched the ball out of Ricky’s hands. It wasn’t easy, he was holding it tightly, but I had the strength of desperation, and Jason’s smile. The ball came loose. It bounced, and as rugby balls often do, bounced on one end, straight back into my arms.

I spun around and streaked for the defensive line. I was halfway up the field before Ricky tried to mow the lawn with his molars (Jason’s description) in the in-goal area. The line was still solid. No matter what happened they kept their defensive line intact. I headed straight for the hardest, heaviest part of the line. Henry Knight.

Henry was massive. He was one of the league’s best tacklers. He was as strong as a gorilla and had over a hundred first grade games under his belt. And he was standing with his legs apart. That, to me, was like an open doorway.

I ran straight at Henry, ducked beneath his clutching arms, slid along the grass between his legs and jumped back to my feet on the other side. I dashed towards the sideline as the sliding defence slid across again. Brad and Bazza White were now guarding the wing, as Ricky was still spitting out grass in the in-goal area.

I ran straight towards them and skirted the sideline even as they reached out to grab me and ‘bundle me into touch’ as the TV commentators put it. Then I put the brakes on. I just stopped.

In slow motion Brad and Bazza bundled themselves into touch in front of me and suddenly there was nobody between me and the goal line.

I almost ambled down to the line, checking carefully behind me so there would be no surprises. I blinked out of the Thing and placed the ball on the black dot between the posts. I looked up, for some reason expecting a roar from the crowd, but there was just a shocked silence. It seemed to last forever.

In the distance, Jason was jumping up and down by the fence; I’d never seen him so excited. Frank was striding on to the field. He looked at me and his voice was calm, although his eyes did not seem happy.

‘I could get fired for this,’ he said evenly, ‘and I don’t know how you’re going to fit it in with your schoolwork, but I don’t reneg on a deal. You’re on the team.’

The other players looked around at each other in amazement, except for Ricky, who stalked past me without a word.

‘Brad,’ Frank said carefully, motioning with his arm. ‘Come for a walk with me. I need to talk to you.’

FIVE

THE LOST PARK

At the end of Manuka Park, not far from the new playground, is the Lost Park. Nobody knows it’s there, except for me, and Jason, Fizzer and Tupai. And this old guy who wears faded, grey track pants and a white sunhat pulled down over his eyes, and jogs, more of a totter really, back and forth, back and forth, hour after hour, every Sunday af

ternoon.

We were on our way to the Lost Park. It was a Friday. Friday the 13th, Black Friday. That didn’t worry us, in fact we thought it was kind of cool. If we’d seen a black cat we would have chased it under a ladder. It was Friday, and that meant that I’d been a Warrior for six days now. Of course, nobody knew outside of the team and my close mates, and I hadn’t actually trained with the team, let alone played a game for them, so I wasn’t really a Warrior yet. But I felt like one.

I had kept it quiet partly because I don’t like to make a big noise about these things, and partly because Frank had asked me to. Something about ‘handling the media’, which I think meant he was worried about how the newspapers and the public were going to take the news.

So I hadn’t told anyone, and I especially hadn’t told Phil Domane, the boy without a brain. Although I nearly let the cat out of the bag when we ran into him on our way to the Lost Park that Black Friday.

We were going down for a kick around. Tupai and Fizzer were tossing the ball back and forth between their bikes, which is quite hard to do really, but they were good at it. Jason and I chatted as we cycled along behind.

Fizzer’s real name is Fraser, but everyone called him Fizzer because he had this really extraordinary talent. Some kids were good at sports, and other kids were good at music, and other kids could balance spoons on their noses or make farting sounds with their armpits. Fizzer could taste the difference between different kinds of soft drink.

He could tell Coca-Cola from Pepsi (although everyone could do that). But Fizzer could tell diet coke from normal coke. He could tell coke out of a can from coke out of a bottle. He could even tell the difference between coke from a two-litre bottle and coke from a 1.25 litre bottle, as long as it was fresh.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

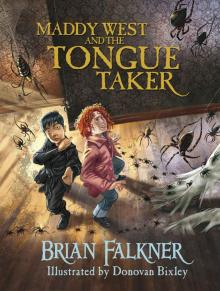

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker