- Home

- Brian Falkner

The Tomorrow Code Page 3

The Tomorrow Code Read online

Page 3

“Okay, try and stay with me on this,” she said, adding a line of code to the computer program she was working on. Tane concentrated furiously on her face, in the hope that by doing so, he might somehow “stay with her on this.”

“I did some reading about quantum foam, and I found out that scientists think it may be possible to detect the stuff, if it exists, by looking for fluctuations in these gamma-ray bursts.”

She stopped, staring at her code for a moment, then added a pair of brackets around part of an equation.

“Go back a bit,” Tane said. “What are gamma-ray bursts, and where do they come from?

“Okay. They are explosions of a type of radiation called gamma rays, which are a bit like X-rays or radio waves but with an extremely short wavelength.”

That didn’t help Tane a bit, but he nodded as if it did.

Rebecca continued, “Nobody knows what causes them, but they seem to come from all over the galaxy. In 1991, NASA sent up a satellite called the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. It has an instrument on it called the Burst and Transient Source Experiment.”

“BATSE!” Tane exclaimed.

“Right, BATSE. It’s the most sensitive detector of gamma rays in the world. What we have on this disk is data from a burst of gamma rays that was received by BATSE this morning. It’s probably just random data from random gamma waves. But if the quantum foam scientists are correct, then the gamma rays could be affected by the quantum foam, and therefore, theoretically, and don’t ask me how, it could be possible for someone in the future to transmit a message using these fluctuations in the gamma rays.”

“Nope,” Tane said. “You lost me at BATSE.”

“Doesn’t matter. We’ll analyze the data and look for patterns. That’s what this program is for. If we find them, great. If not, well, it was a wild idea to start with.”

She pressed a couple of keys on the keyboard and said, “Hold your breath.”

Tane looked at the screen and waited, but apart from a single, flashing cursor, nothing was happening.

“What’s it doing?” he asked.

“My program looks for patterns. It could take a while, though; there is a lot of data to look through, and the patterns could be quite complex. But if it finds a series of numbers that form a definable pattern, it will stop and we’ll be able to look at it.”

“Okay, cool,” Tane said, although he had really been hoping that it would have been flashing colors and weird patterns on the screen as it worked, a bit like the ambience patterns you got on Windows Media Player.

They watched the flashing cursor for a bit, but it got very boring very quickly.

“Why wouldn’t NASA have found these patterns?” he asked after a while.

“They’re not looking for them,” she said. “They’re trying to find out what causes the bursts. They think it might be two neutron stars colliding, or maybe a neutron star being swallowed by a black hole.”

“Really,” Tane said, nodding his head and wondering what on earth she was talking about.

“There are some scientists from Texas who are looking for fluctuations, but they’re trying to prove the existence of quantum foam, and they’re still trying to work out what a quantum gravity signature would look like. Nobody is looking for messages in the rays.”

“Just us.”

“As far as I know.”

Tane watched the cursor for a while longer, then turned and looked at his friend, looking at the cursor. Her eyes never left the computer screen.

He had known Rebecca all of his life. A lot of people said things like that, but in their case it was true. They shared the same birthday, and their mothers had shared a maternity ward at the hospital. They had even lived close to each other in those very early years, before Tane’s father’s career had taken off and he and Tane’s mum had built the big house amongst the trees up in the mountains. Tane and Rebecca had played together in kindergarten and now went to the same high school. For nearly fifteen years, there had never been a time when he had not known the spiky-haired girl sitting next to him.

“I’m going to miss you when you go to Masterton,” he said.

Rebecca said quickly, “Don’t forget the march tomorrow. We need to get down to the station before nine to catch the bus into the city.”

“I’ll set my alarm clock,” Tane promised.

SAVE THE WHALES

On the day of the big march, Rebecca got arrested. The Japanese prime minister was visiting Auckland. What he was doing there, Tane wasn’t sure. Some trade summit or international congress of some kind; he didn’t really know or care.

The protest march was set to start at the same time as the prime minister’s flight arrived at the airport, which was mid-morning on Saturday. It would wend its way up through the central city, arriving at the prime minister’s hotel just about the same time he would be.

Tane gripped his placard with both hands and held it high. Just to show his support for the cause. The cause was something to do with whales and saving them from Japanese whaling boats, but it was actually more complicated than that and had something to do with fishing quotas and scientific whaling and all sorts of other things that he was sure were worth fighting for, or against. Whichever it was.

Rebecca certainly believed so, and Tane couldn’t let her march by herself. He hadn’t let her march by herself on the anti-nuclear march or the anti-GE (genetic engineering) march, although he’d had the flu on the day of the climate-change march, so she had done that one by herself.

There had probably been a time when Rebecca didn’t feel strongly enough about some issue to want to march in protest about it, but that was probably when she was in preschool, and Tane couldn’t remember it.

He thought most people in the difficult situation that Rebecca now found herself in would have lost interest in protest marches. It was she who needed saving at the moment, not the whales. It could have been another excuse to take her mind off her problems, but Tane thought it was rather more than that. He’d known Rebecca a long time, and he knew that when she committed to something, she always saw it through.

Which was why they were both there at the very front of the marchers. On the front line of the battle, as it were.

A long swelling chant began at the back of the line of marchers: “Ichi, ni, san, shi…don’t kill whales, leave them be. Ichi, ni, san, shi…”

“What’s this itchy knee business?” he asked Rebecca in a quiet moment between chants.

She rolled her eyes. “It’s ‘one, two, three, four’ in Japanese. It’s because the—”

“Yeah, yeah, I get it now,” Tane said as the chant began again.

“Ichi, ni, san, shi…don’t kill whales, leave them be!”

“Thanks for coming, Tane,” Rebecca said after a while.

“Gotta save those whales!” Tane said enthusiastically, waving the banner around and accidentally clouting a large man with a shaved head who was wearing a leather jacket and marching next to them.

“Sorry,” Tane said.

The man grinned and nodded to show that no harm was done.

It was an officially sanctioned, organized march, which meant that the road was blocked off by police cars with flashing lights at each intersection along the route.

Another police car preceded them, rolling slowly forward just a few yards in front of Tane and Rebecca.

Along the way, early morning shoppers either raised their arms in the air and shouted in solidarity or just stared curiously at the throng, which was wide enough to completely cover the roadway and stretched away behind them. There had to be a thousand marchers, Tane thought, although he wasn’t much good at estimating the size of crowds.

The march started down on the Auckland waterfront and proceeded straight up Albert Street to the huge Sky City casino complex, with its massive three-hundred-sixty-yard-high Skytower.

They turned right just before the casino onto Victoria Street, then stopped at the entrance to Federal Street, where t

he Japanese delegation’s hotel was.

Wooden barricades prevented the marchers from entering the street, so they had to wait, milling and chanting, completely blocking the road.

It didn’t take long for the prime minister’s motorcade to arrive. First came a police car, then a large black van that had to be filled with security guards. Then a long black Mercedes limousine.

The chanting rose to a crescendo as a line of police officers formed a human barricade behind the wooden one. Behind the blue line of police, Tane could see the slender figure of the Japanese prime minister emerge as a large man in a dark suit opened the door of the limousine and stood to attention.

Several New Zealand dignitaries that Tane didn’t recognize stood in front of the hotel, waiting to greet the man.

And that might have been the relatively peaceful end of it, if it hadn’t been for the prime minister stopping as he got out of the car, turning to the protestors, and waving cheerily.

Maybe he was just being friendly. Maybe he was waving to someone he knew. But it was the worst thing to do to a crowd that had been winding itself up, chanting and shouting over the past twenty minutes while marching. It was like pouring gasoline onto a barbecue.

There was an angry roar from the crowd, like that of a wounded animal; then suddenly the wooden barricades were down, toppling under an onrush of protestors. The police linked arms and stepped forward to meet the onslaught. Behind them, more police officers drew batons and waited.

The Japanese prime minister and the other dignitaries scurried toward the hotel, all thoughts of ceremony vanishing in the face of the wild beast that lunged toward them.

Tane tried to push himself backward, but it was impossible with the press of the crowd behind him, and he found himself crushed up against a huge policeman with a beard and bad breath. The air squeezed out of his lungs with the pressure from behind, and an overwhelming feeling of claustrophobia enveloped him.

The thin blue line held, though, the storm of protestors safely contained on the outside. All except one, Tane saw through a thin gap in the blue uniforms. A small, quick shape, a blur of movement, and Rebecca was halfway toward the Japanese delegation, dodging around the larger, slower policemen like a rugby player evading tacklers.

She almost made it, shouting and screaming something about whales and murder, when one of the large, dark-suited men grabbed her by the arms, pinning her and forcing her to the ground.

At that point, the line fractured and split apart in a dozen places, the fury of the crowd intensifying as one of their own was attacked. Suddenly there were protestors running everywhere, some battling police batons with their makeshift placards.

The bearded policeman whirled away from Tane, and he managed to fight his way sideways, unable to see Rebecca, unable to do anything but try to claw breath back into his lungs and get out of the running, crushing crowd.

He found a small oasis amongst the huge concrete pillars at the base of the Skytower and slumped to the ground, exhausted.

In the end, they had to call in the riot police to clear Federal Street. Over a hundred people were arrested, but most were released without charge after being processed at the Auckland Central police station, just a few blocks away.

Tane waited outside for four hours until Rebecca finally emerged, bruised and disheveled but defiant.

“That was awful,” she said. “They photographed us, took our fingerprints, and jammed us all into these tiny cells while someone decided what to do with us.”

“I tried to get to you,” Tane said, which wasn’t really true but seemed like the right thing to say.

“You couldn’t have done anything,” Rebecca said. “They had me into the police van in three seconds flat. In handcuffs!”

She rubbed her wrists, and Tane could see red marks where the cuffs had been.

“It’s so unfair,” she raged quietly. “They’re the criminals, killing whales and calling it research, but we’re the ones who end up with a criminal record!”

“Don’t worry about it,” Tane said. “You’re still a kid. They have to erase all record of the arrest the day you turn eighteen. I read that somewhere.”

She was silent.

“Really,” he insisted, trying to make her feel better. “It’s nothing. It won’t matter at all.”

He was wrong, though—as it turned out, Rebecca getting arrested mattered quite a lot.

111000111

Tane’s computer was very new and very powerful. It had a shiny silver case and a flat nineteen-inch screen, with a cordless mouse and keyboard. It was very expensive. He’d gotten it for his fourteenth birthday, so it was pretty much the latest processor, and it had a lot of memory, a fast hard drive, and a high-powered graphics processor, and it was generally really quick at anything, especially games.

So it was a little bit hard for Tane to understand why it was taking so long for it to run Rebecca’s program. She started to explain it to him once or twice, but her explanation about the program code made no more sense to him than the code itself.

The only good thing was that once it was running, it kept running all by itself, without needing assistance from anyone. Not that Tane felt he would be able to give it any kind of assistance anyway.

They had started it running on Friday night, the day before the protest march, and it was still running the next Sunday. And Monday.

More days passed. A week. Then another. Sometimes Tane would wake up during the night and would feel that the insistent flashing of the cursor was reaching out to him. But mostly he just wondered if it was really doing anything at all, or if it was just stuck in some mindless loop because of some bug in Rebecca’s program.

A third week went by. That week, Rebecca had another date with Fatboy, although she said she didn’t feel very much like dating, with all that was happening. But she went anyway. That night, the flashing cursor seemed like a warning light.

The day of the auction, November 14, was the day that the program finally paused and displayed some data on the screen, but Tane wasn’t there to see it. Neither was Rebecca. Painful as it was, they were both at the auction.

It was a bright, chirpy day and for that reason the auctioneer, who looked just like a dapper little English gentleman but who spoke with an Australian accent, held the auction outside in the small backyard. Tane had mown the lawn, and they had both spent an entire weekend weeding to make the place presentable. He thought it looked as good as it could look, as the potential buyers, the tire-kickers, and the nosy neighbors gathered around.

The auction turned out to be a disaster. It was over in less than ten minutes, and the house, Rebecca’s family home, sold at a bargain-basement price to some flamboyantly dressed young entrepreneur.

Rebecca shuddered once or twice as the hammer fell, and Tane put his arm around her shoulders.

At that price, Rebecca and her mother wouldn’t even be able to fully repay the bank. They’d have to keep making mortgage payments, plus pay the creditors, and they’d have no money for the move to Masterton. It was an all-around disaster.

Rebecca was crying silently as Tane led her inside. He offered to make her a cup of cocoa, but she shook her head and said she wanted to go to bed for a while.

He rang his mum and told her he’d be home a bit later than expected. She didn’t mind and asked if there was anything she could do to help, but there wasn’t really.

When dinnertime came, he found a few bits and pieces in the cupboards and the freezer and made some savory pancakes, but neither Rebecca nor her mother would eat them.

He ate them himself at the dining table, which was still covered in mounds of paper, and a bit later, he went to check that Rebecca was okay.

He pushed the door open noiselessly. The light from the hallway spilled inside. It was not a little girl’s room, and it was certainly not a typical teenage girl’s room. In place of the posters of boy bands, there were posters for Greenpeace and Amnesty International. The books on her bookshelf wer

e by Stephen Hawking and Salman Rushdie, rather than Meg Cabot or Jacqueline Wilson.

She was lying on top of the bedcovers, still fully clothed but sound asleep. In sleep, the heaviness and the tiredness lifted from her face, and there was a stillness and a calm about her that wrenched Tane’s heart.

He pulled a blanket over her and gently brushed his hand against her cheek by way of a goodbye.

It was still light, but only just, when he stowed his cycle in the garage and wound his way up through the many levels of his parents’ house to his room, and there, waiting for him on the screen, was a long line of ones and zeros.

Rebecca’s software had found a pattern.

“Thanks, Tane, thanks for everything.” Rebecca smiled at him tiredly over the Sunday-morning cup of cocoa he’d made her. He’d quietly let himself back into the house at about eight, using Rebecca’s key, which he had borrowed on his way home the night before. “You’re a good friend. We’ll keep in touch, after I move down to Masterton, won’t we?”

“Of course we will,” Tane said. “We’ll probably be on the phone every night, and I can come and visit you on long weekends, stuff like that.”

She smiled and nodded her agreement, although they both knew that it would probably never happen.

She said, “Yesterday was such a nightmare. I don’t even want to think about what we’re going to do now.”

“When do you think you’ll leave?” Tane asked.

“I dunno. I think the settlement date is in about three weeks, and we’ll probably have to be out before then. I expect I’m going to have to organize it. Mum doesn’t seem to want to have anything to do with it. I don’t know how we’re going to pay for it, though.”

Tane had a thought and said, “Maybe my mum and dad can help out. A loan of some kind.”

Rebecca looked down at her mug. “I’d say no and tell you that we’re too proud and all that. But I guess we’re not. We’re just desperate.” She laughed. “I just hope my BATSE analyzer finishes running before we leave.”

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

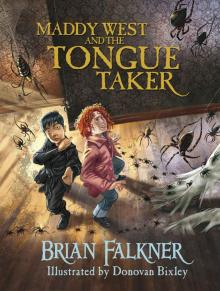

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker