- Home

- Brian Falkner

Clash of Empires Page 7

Clash of Empires Read online

Page 7

“I take no offense at your ignorance,” Monro says mildly. “I will advise you once again to leave.”

“Advice that I cannot in good conscience take,” Frost says.

“In which case I will send for the provost marshals, and you will all be arrested,” Monro says.

“They will have to drag me from this room,” Willem says. “I will not leave my friend to such barbarity.”

“Barbarity?” Now Monro’s careful calm threatens to break. “Barbarity? How dare you, sir?”

“Major Lux, we must leave,” Frost says. “But this afternoon we will have the ear of the Duke of Wellington. Perhaps he will be able to sway the doctor’s mind.”

“The Duke of Wellington.” Monro snorts. “A pompous fool. I will not be directed in medical matters by those with no medical knowledge.”

“You will be hearing from us again,” Frost says. “Jack, please guide me.”

Jack releases Adams, who gets slowly to his feet, staring up at Jack with cold eyes. Jack takes Frost’s arm and leads him from the room.

As Willem reluctantly follows he looks back. Adams has returned to the handle and is smiling at Willem as Héloïse once again starts to turn on that awful chair. Each time she turns her eyes meet Willem’s. He sees nothing but loathing.

* * *

Willem waits until they are outside the main gates and approaching the hackney carriage before he risks speaking; his pulse is racing and his voice does not seem his own.

“A madman is in charge of the madhouse,” he says.

“She must not stay in that place,” Jack says, wiping tears from his eyes.

Willem grasps Frost by the arm. “How could you leave her in that torture room?”

“I would not,” Frost says. “But if you and I are arrested, then there will be nothing more we can do for her. However, there are many ways to skin a gardensaur. The duke has great influence. Let us see if he can help.”

Willem looks back as the carriage takes them away from the asylum. The last wisps of morning fog swirl around the building and the low sun strikes up under the eaves, creating hollows out of the window spaces. The asylum seems to radiate an evil presence.

“And if the duke cannot help?” Willem eventually asks.

“Then you will have to magic her out of that place,” Frost says.

ROCKETEERS

The spinning, smoky tail of a rocket corkscrews straight into Lewis’s mouth and explodes in a fiery burst, setting the head on fire.

Willem watches in silence. He has been silent for most of the trip back from Bedlam, his mind filled with the horrors of what he has seen. Of the degradation and humiliation of his friend. They have arrived back at Woolwich barely in time for the display by Sir William Congreve’s rocketeers.

Lewis’s head falls from its wooden neck and lies burning on the grass of the field. Willem glances sideways at Jack, who stands motionless and emotionless. Willem thinks of the hours of painstaking work Jack put into carving Lewis, and he thinks of the friend that it represents, lost at Waterloo. He sets his jaw, knowing what Jack must be feeling.

Fortunately for Jack, but unfortunately for Congreve, it is the only rocket of the first barrage to get anywhere near the five wooden trojansaurs dragged out by Congreve’s horse crews to the wide-open training fields past the parade grounds.

The Duke of Wellington and Lord Wenzel-Halls, the Earl of Leicester, are seated on armchairs at the front of the viewing area. The chairs look out of place in the middle of a grassy field.

The duke is elegantly dressed in his red uniform tunic and his cockade hat. He wears a curved Mameluke sword and looks every inch the British nobleman, far different from how he looked in the plain gray coat he wore the last time Willem met him. The earl is a stout man, an old-fashioned one with a heavily powdered wig and stockings that would not have looked out of place in the previous century. He wears no military uniform. He dabs his bulbous nose regularly with a brown-stained handkerchief, a sign of a regular snuff user.

Next to the duke and the earl on simple wooden chairs are Lieutenant Colonel Sir George Adam Wood, the commander of the Royal Artillery, and Lieutenant Colonel Frazer, the commander of the Royal Horse Artillery, along with Congreve, the rocket master. Frost, Willem, Jack, and the other spectators stand in a roped-off area behind them.

The skies are clear and the whole event has the feeling of a gala. At least it did until the five trojansaurs were wheeled onto the field. It’s all of them except Harry, who is in the workshop for repairs to his face. Any warmth in the day immediately evaporated as Willem realized what was about to take place.

Lewis’s head still burns fiercely as the rocketeers reload their weapons. Gray smoke spirals into the clear sky.

“What is happening, Jack?” Frost asks. “You are to be my eyes, remember.”

“Sorry, sir, I was just a bit shocked, sir,” Jack says. “The rockets all missed, sir, except for one. That hit Lewis.”

“Any damage?” Frost asks.

“He’s on fire, sir,” Jack says matter-of-factly. “And his head fell off.”

As the rocketeers reload, Sir William Congreve stands and turns to face the audience. He has an object in his hands. A long, sleek rod with a barbed end. He gestures dramatically at the burning trojansaur with it.

“Welcome to the future,” he says. “Napoléon fights with ancient animals. We will defeat them with modern military technology.”

This earns light applause.

Congreve holds up the object. “If this is the first time you have seen our rockets in action, let me explain how they work,” he says. “Like case shot, our rockets contain an explosive charge. Gunpowder also gives us our propulsion, with a range of well over three thousand yards. But today we are firing at a much closer range. We have lowered the elevation to simulate what might happen against dinosaurs on the battlefield.” He points to the sharp barbed end. “We have developed a harpoon-like head to ensure that the rocket will penetrate and cling to a dinosaur’s skin until it explodes, killing the beast. Not all the rockets will find their targets, of course, but even those that miss will disorient and frighten the creatures. A maddened, panic-stricken dinosaur would be equally dangerous to friend or foe.”

He finishes to a loud round of applause.

“He has borrowed your words,” Frost murmurs.

Willem shrugs. “It is a fact; it does not matter who says it.”

Congreve retires to his seat and gives a signal to the rocketeers.

There is a series of small explosions from the field and smoke erupts from the ground, swathing everything in a light blanket of haze.

“They’ve let off some smoke bombs,” Jack says quietly in Frost’s ear.

“Yes, I can smell it,” Frost says. “To simulate battlefield conditions, no doubt. Congreve clearly likes his theatrics.”

From off to one side in the trees comes a low, reverberating growl. It has a flat, tinny sound to it.

“What the ’ell is that?” Jack asks.

“I imagine it is supposed to be the bellow of a battlesaurus,” Frost says. “Probably just a man in the trees with a large speaking horn.”

“I don’t think he has ever heard a dinosaur roar,” Willem says.

“Sounds more like a sick cat,” Jack says.

“Or a cow giving birth,” Frost says.

“Or a cat giving birth to a cow.” Willem laughs.

The rocket-launching contraptions look like ladders, propped up with wooden legs, creating a triangular shape pointed toward the targets. The legs of the ladders have metal troughs. A rocket is placed on each trough.

The firing mechanism is a metal shape not unlike the stock of a pistol, with a frizzen, a firing pin, and a long lanyard. When all the soldiers are ready, they stand well clear of the tails of the rockets. Bombardiers wait for the order to fire.

Congreve raises his hand, holds it there for a moment, and then brings it sharply down. The bombardiers pull on their lanyards a

nd there are puffs of smoke from the firing mechanisms, followed by sparks sputtering from the ends of the rockets. The rockets wriggle their tails for a second or so, then shoot forward with a loud hiss, leaving trails of smoke behind them.

“I do not hear the sounds of damage this time,” Frost says after a few seconds.

Jack has been too relieved to say anything. Now he does. “They’ve all missed,” he says, trying not to sound too cheerful. “Some has gone straight ahead, but not very near me wooden monsters. Others has gone all over the place, sir, up, down, off to the left or right. It’s a right queer mess, sir, if you ask me.”

“Just a little more quietly, if you please, Jack,” Frost says.

Willem is aware of faces turning to look.

“Sorry, sir,” Jack whispers. “Now the rocket men are reloading again, sir.”

The rocketeers repeat the process of loading and arming the rockets, but this time do not wait for a signal from Congreve.

In twos and threes another barrage of rockets spark, sputter, and hiss through the air.

Jack keeps up his quiet commentary. He describes the scene as one rocket spirals into the ground just in front of its launch ramp. The rocketeers all dive to the ground as it explodes with a huge thump, throwing dirt and grass into the air.

The rocketeers stand up as if nothing unusual has happened and start to reload.

“Don’t think I’d like to be a rocket man,” Jack says. “Looks a bit dangerous to me.”

“More dangerous to the troops than to the dinosaurs?” Frost asks.

“So far, sir,” Jack says, but the words have barely left his mouth when the barbed nose of one of the rockets embeds itself in the wooden framework of Dylan. It protrudes from the splintered wood, still smoking.

“They’ve hit one,” Jack says, trying to sound calm. “It ain’t done much damage though, sir, it—”

The rocket explodes, destroying the neck of the creature in a shower of splinters and wood chips.

“What just happened, Jack?” Frost asks.

Jack has shut his eyes tightly. He opens them as the carved wooden head of the creature cracks into two pieces and topples, on fire, to the ground.

“They got Dylan, sir,” Jack says.

Behind them somewhere McConnell calls out, “Good shot!” and there are cheers and applause from the rest of the audience. But the sounds quickly turn to cries of alarm, then horror, as one of the other rockets takes off almost vertically from its launcher, flying high into the air, then dropping in flames, a fiery falling star heading straight for the viewing gallery.

“Look out, sir,” Jack cries. “It’s coming right for us!”

“Don’t be so dramatic, Jack,” Frost says, not moving.

The rocket veers off at the last second and dives into the dirt just in front of the Duke of Wellington. The earl, seated next to him, cringes and raises his arms, but the duke does not move at all. There is an eruption of flame from the ground for a moment, but no explosion.

As the flame burns out there are more cheers and applause.

“We’re all right, sir,” Jack says. “The rocket didn’t blow up.”

“Well and good then,” Frost says.

Barrage after barrage of rockets is fired. Still the three remaining trojansaurs are unharmed. Some rockets head skyward on twisted trails of smoke, others bury themselves into the earth. Some hurtle off sideways into the trees that line both sides of the field and one loops high into the sky, over the tops of the trees and into the town beyond. A rider is sent to check on any damage or casualties.

After half an hour of the barrage, a constant roar of hisses and explosions, another of the targets is hit: Ben.

Jack seems unable to speak for a moment as the rocket flies straight into the chest and explodes, tearing the structure to pieces. Behind him, McConnell celebrates with a whistle and the applause from the gallery is long and loud.

“They killed Ben,” is all Jack can say.

Sam is next: a rocket lodges in the gun carriage and although it does not explode, it burns fiercely, setting fire to the framework, then the head. Thick smoke boils away upward. Douglas collapses when a rocket blows off one of its wheels.

There is applause and cheers when the demonstration finishes and the rocket troop gallops away. The trojansaurs—blackened, fragmented, or still burning—are left where they are.

“That’ll show Bony,” Jack hears Lieutenant Colonel Wood say. The duke nods and smiles but does not comment.

As they leave, they come face-to-face with McConnell, who smirks but says nothing.

“Thank you for your commentary today, Jack. You did a good job,” Frost says as they walk back to the barracks. “You were a great help. Would you consider a transfer onto my staff?”

“Sir, I’d love that, sir,” Jack says. “But what would I do, sir?”

“I’m sure we’ll find something to keep you busy,” Frost says.

THE DUKE

A late luncheon has been prepared in honor of the duke’s visit. Willem attends in the role he is playing as a major of artillery, and Frost as a representative of the Intelligence Service.

To Willem’s eye, the luncheon is a feast to more than rival even the best years of the spring festival in Gaillemarde. The table is loaded with soft, moist roast pork, golden potatoes, and fresh fruit. There are bowls of grapes, red, green, and yellow. Bread rolls are stacked in towers and jugs of sauce are full to overflowing.

The duke sits at the head of the table with the Earl of Leicester, along with the two commanders of the foot and horse artillery, Lieutenant Colonel Wood and Lieutenant Colonel Frazer. Congreve sits to the duke’s left.

Frost draws Willem aside before they take their seats.

“The duke is a difficult man,” he says. “He is fair and honest. But he does not suffer fools gladly.”

“So you think me a fool,” Willem says.

“Not in the least, and that was not my meaning. But you must take care what you say lest the duke forms that opinion.”

“So the duke thinks I am a fool?” Willem asks.

Frost sighs. “I am privy to many things. Things that I cannot discuss with you. Regardless of what agreement you had with the duke, the world has changed. He will not honor an agreement with a peasant boy if it means losing a war.”

“We will see,” Willem says stubbornly.

“You must present him with sound arguments,” Frost says. “Make him realize that what you suggest will help him, not hinder him. You—”

He seems to want to say more, but must stop as the duke sits, which is the signal for the other officers to take their seats. As the shuffle of boots and scraping of chairs dies away, Willem hears that the conversation at the head of the table has already turned to the rockets.

“A most able display,” the earl says. “Let Bony come. Let him bring his blasted dinosaurs. We will kill them and then throw his Grande Armée back into the sea.”

The duke does not seem to share his enthusiasm. “Frazer, you were in the thick of things at Waterloo,” he says. “What is your opinion of the rocket display?”

Frazer, a fine-featured man with piercing eyes, takes a long sip of wine before answering and the table goes quiet, waiting for his response.

“My lord, I must defer,” he says. “There was much smoke and confusion on the battlefield at Waterloo. It was all over in an instant and although I saw the creatures, I am not able to say how the rockets might fare against them.”

“A shame,” the duke says.

“Might I instead pass the question to the saur-slayer, the hero of Waterloo,” Frazer says. “Young Lieutenant Frost, who was in the midst of the action and managed to kill not one battlesaurus, but two.”

All eyes turn to Frost, who seems aware of it despite his blindness. He draws his handkerchief and coughs lightly into it before speaking.

“Your Grace, might I be permitted to speak plainly?” he asks.

“That is what we want,�

� the duke says.

“And my plain speaking should offer no offense to Sir William, whom I regard as a genius and a personal hero of mine,” Frost says.

“None will be taken,” Congreve says, smiling politely.

“I think it was a wonderful demonstration today,” Frost says. “Although I could not see it, I heard it well enough and Private Sullivan, who now acts as my eyes, described it vividly for me. I understand that all five of the available wooden dinosaurs were destroyed.”

“Indeed they were, Lieutenant,” Congreve says proudly.

“And the demonstration lasted what, an hour?” Frost asks.

“Less,” the earl says.

“Merely fifty-two minutes by my timepiece,” Frazer agrees.

“On the battlefield at Mont-Saint-Jean, it was all over in a fraction of that,” Frost says. “From when the battlesaurs charged out of the Sonian Forest to when my ammunition caisson exploded could not have been ten minutes. The creatures are quick and agile. It was great skill on behalf of my crew that we were able to turn our gun rapidly enough to kill one of the creatures as it attacked. The second was pure luck. We had no time to reload.”

“Then what happened to it?” the earl asks.

“It was killed by our exploding caisson, as nearly was I, and Sullivan, my spongeman, the only survivors from my team.”

“Then you regard today as a failure, lieutenant?” Congreve asks, his eyes hard.

“I do not, Sir William,” Frost says. “I regard it as neither a success nor a failure, but rather as a distraction. I fear that firing an hour’s worth of rockets at stationary targets is so far removed from the reality of the battlefield as to provide no useful evidence as to their effectiveness.”

“I am outraged, sir—” Congreve begins, but stops as the duke holds up a hand.

“You have no right to outrage,” the duke says. “The lieutenant asked for, and was given, permission to speak plainly. He has a firm opinion, and quite frankly, as he has firsthand experience of these animals, I feel his opinion should carry some weight. I also was disturbed at the time it took to destroy the targets today.”

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

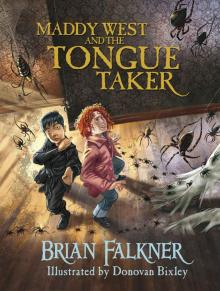

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker