- Home

- Brian Falkner

The Flea Thing Page 7

The Flea Thing Read online

Page 7

The fastest Warrior of all time, they called me, a title that used to belong to Ricky Albany.

Henry missed the first game but was fully fit for the second, against the Broncos, and we played like demons, eventually taking the mighty Broncos down 34 to 28 and knocking them out of the tournament.

The other team that was knocking teams aside with a flyswatter was the Machetes. They hadn’t been expected to do very well this season but when it came down to the wire it was them and us. The Machetes versus the Warriors for the season Grand Final.

We flew to Australia a week before the Final and the Sydney Roosters lent us their fields and facilities for the lead-up training. Nice of them really.

The week was full of activities. We were treated like movie stars and the official Grand Final Breakfast was something else again.

On the morning of the big day I woke up extra early. I just couldn’t sleep. I sort of dreamed my way all through the team’s carefully calibrated, nutritionally balanced breakfast and the rest of the day passed in a bit of a blur. Right up until just before game time.

Frank called me up into the Coaches’ box as preparations for the Grand Final swirled all around us. He motioned for the others to leave and asked me to sit down. I sat, feeling like the same brave twelve-year-old with the messy black hair and freckles who had sat in front of Frank all those months ago.

‘You’re a Warrior, kid,’ he said, ‘and one of the best I’ve got. And you’re only thirteen years old. What are you going to be like when you’re twenty?’

I just smiled and shook my head. Frank was heading somewhere but, unusually for him, he was taking a roundabout way of getting there. He said, ‘I strongly believe that if it wasn’t for you, we wouldn’t be in this Grand Final this year.’

‘The first day I met you, I promised you that if you put me in the team, you’d win the premiership.’

Frank nodded, then shook his head as well. ‘I remember, but we haven’t won the premiership yet, we’ve still got to beat the Machetes one more time. And that’s what I wanted to talk to you about.’

I was getting a strangely uncomfortable feeling, but I let him continue.

‘You’ve seen the style of league the Machetes have been playing. If I put you on the field in the Grand Final I might as well paint a target on your forehead.’

This was not sounding good. ‘Do you want to win the premiership?’ I asked, a bit nervously.

‘Yes, I do, kid. Yes I do. I want to win the premiership very much. But ask me another question. Ask me if I want to win it, if it means you get seriously injured … or worse. Then the answer is no. No, I’d give it away in a millisecond.’

‘I won’t get hurt. I can look after myself.’

‘Flea, Daniel, you could win the game for us today. You know that, I know that, and you can bet your rugby boots that the Machetes know that. They’ll target you and they’ll hurt you to take you out of the game. Do you understand that? You saw what they did to that monster Henry. What is going to happen to a scrawny insect like you?’

‘Scrawny!’

Frank held up a hand so I’d know not to get angry. ‘You get injured today, and you might not be playing when you’re twenty. You might not be walking.’

‘I can handle it.’

‘I don’t want you to.’

‘Frank …’

‘Flea, listen to me. If it was entirely up to me I wouldn’t even have you on the reserves’ bench today. I’m not going to put you on the field, so really you’re just taking up a space that I could have used for someone else. But you know what?’

‘What?’

‘I couldn’t do that. You’ve become a bit of a star. If I had named the team for the Grand Final and hadn’t named you in it somewhere, I’d be lynched by the fans. So you’ll be on the bench. And that’s where you’ll stay. And don’t go complaining to me, or anyone else, about it. The decision is mine and the decision is final.’

I was blinking back tears as we were waiting in the dressing room for the pre-match entertainment to finish.

Henry saw at once that something was wrong but he couldn’t work out what.

‘You OK, Flea?’

‘Yeah, I guess.’

‘What did Frank want?’

‘Just a chat.’

‘You are playing today, aren’t you?’

I looked down the tunnel, away from my friend, and told him. ‘I’ll be on the bench, in my usual place.’

‘That’s good.’ Henry looked relieved. ‘I was afraid he wasn’t going to play you. Have Jason or any of your friends come over for the game?’

He must have seen something in my face because he asked, ‘What’s going on, Flea?’

And so I told him.

I told him about Jason and Jenny, and Phil and Lost Parks and Smart Farts and everything except the voodoo doll. I was a bit embarrassed about that.

Henry just looked at me. For a very long time. He didn’t say anything. Neither did I because I knew Henry well enough to know what that silence meant, and we both felt comfortable with it. Finally he said, ‘I know what it’s like to be thirteen.’

There was a huge cheer from the stadium for some part of the pre-match.

‘When you’re thirteen, you just want to be fourteen. When you’re fourteen you can’t wait until you’re fifteen. Fifteen wants to be sixteen, and on it goes. And then you get to thirty.’

‘And you want to be thirty-one?’

‘No.’ There was a trace of regret in Henry’s voice. ‘You’d give anything to be thirteen again.’

He spoke with a smile that softened the words he had to say but did not change the meaning. ‘Flea, if you live to be a hundred and thirteen, you will never again have friends like those you have when you are thirteen. We’re buddies. And I like being your buddy. But Jason’s your mate.’

I said sullenly, ‘If he was my mate he wouldn’t have called me a smart fart. And he certainly wouldn’t have told Phil about the Lost Park!’

‘OK. Jason did a bad thing.’ Henry looked me straight in the eye, the way he did when he was giving me advice about playing league. ‘He did a bad thing. It doesn’t make him a bad person.’

I blinked twice and Henry froze. My breath caught in my throat. I didn’t often, well almost never, use the Thing when I was just talking to people, but I needed time to think.

Jason did a bad thing. It doesn’t make him a bad person.

Henry wasn’t very smart. He was big, strong and athletic, but he was a simple kind of guy and he was the first to admit it. Yet somehow he had a simple way of looking at things that cut through all the rubbish that the rest of us had to think about. He was right. As much as I hated to admit it, he was right.

Henry, in slow motion, was opening his mouth to speak and I flicked back into normal time. ‘How many good things has Jason done?’

‘Well …’ I could think of hundreds, not the least of which was that time at my try-out when just his belief in me had got me into the Warriors’ team. ‘Lots, I guess.’

‘The way I see it, when you do something good, that’s like making a deposit in your bank account.’

‘I don’t have a bank account,’ I interrupted, but continued quickly, ‘but I see your point.’

Henry continued as if I hadn’t spoken. ‘Doing good builds up credit in the account. Doing something bad is like making a withdrawal. If you do too many bad things, well … you end up in overdraft and I guess at that stage you gotta wonder if the person is really your friend.’

I said quietly, ‘I understand.’

‘So is Jason in credit or overdraft at the moment?’

‘He’s in credit. A lot of credit.’

‘So …’ Henry smiled that big, simple smile of his. ‘That’s that then.’

We got our call and stood up to move out into the tunnel. I said, ‘Thanks, Henry.’

‘That’s what buddies are for. Have a blinder today.’

‘You too, mate. You too.’

<

br /> Looking back now, that’s the moment I can pick when I started to ‘grow down’. I’d been trying so hard to grow up quickly that I had missed out on a lot of what being a kid was all about. So I grew down. I just sort of settled into being a kid again.

FIFTEEN

THE GRAND FINAL

The Grand Final started well. In fact the first half was another tight, tense game of rugby league between two evenly matched sides. Which was all very well, but the second half was a nightmare.

The Grand Final was at the massive Stadium Australia that had been built for the Sydney Olympics. The atmosphere at a Final is like no other game, from the pre-game entertainment on.

The Machetes ran out first but we had a surprise in store for the crowd. Rather than run out from the tunnel in the traditional way, we waited for our music. It had all been arranged in advance. It was Whiney Whiney by Willi One Blood; the song Henry had played to me in the car. It was my idea, but the whole team had got behind it, and even Frank thought it was great.

We didn’t run out, instead we all formed a single file and slow-marched out in this kind of Egyptian style. The crowd roared. They loved it! The Machetes just stood around on the pitch shaking their heads. They had been totally upstaged, and they knew it.

You can play all the club rugby league you like, you can play sell-out games at your home stadium and sit in front of TV cameras broadcasting your picture to millions of people around the world, but until you’ve stood on the pitch in front of the solid wall of sound of eighty thousand roaring rugby league fans at an NRL Grand Final you can’t imagine what it feels like. Everything that had gone before suddenly seemed dull and grey compared to the colour and spectacle of the Grand Final.

They played the national anthems of New Zealand and Australia before the match. I don’t know why because it wasn’t actually an international, but it was still stirring.

I sat back on my seat on the reserves’ bench after the anthem and prayed that Frank would let me play. He didn’t, of course, and I caught Ricky Albany, the second-fastest Warrior of all time, smirking at me just before kick-off, which soured things a bit.

The first half was a thrilling tug of war. It took twenty minutes for a single point to go on the board, and that was a penalty to the Machetes. Five minutes later, though, Ricky touched down in the corner and Fuller converted the try to make the score six: two.

The Machetes hit back just before half-time and missed the conversion, so the score came to six all. All that effort and both teams were in exactly the same position as when they had started the match.

The second half was just embarrassing. Ainsley, who has the safest hands in the competition, fumbled the ball on the kick-off and the Machetes scored from the scrum that followed. We looked like we might hit back a few moments later, but Streakson, their flying winger, intercepted Bazza’s pass to Brownie and ran eighty metres to score another try. By the time Rumble Bean had barged over for a third unanswered try in the seventy-sixth minute it was looking like a rout. Rene Philips converted the try and from that moment on the game was lost.

We were sixteen points down with just over three minutes to go. To win we would have to score three tries, and convert them. It just wasn’t possible. The commentators were already talking about a great Machetes’ victory and how it had capped off a stellar first year for the club, whatever that means.

Frank had gone quiet. Terrifyingly quiet. The walkie-talkies in the trainers’ hands were empty of his normal crackly chatter. I guess on his mind must have been the missed tackles, the bungled try and the ref’s decisions, which had gone against us all night. This time I think he had really thought we could win it. A first for the club. A first in the history of the competition. Now just a might-have-been.

A Mexican wave was running around the ground, congratulating the Machetes. It passed behind me with a roar and a couple of empty paper cups and bits of paper floated down to the ground in front of me.

I turned to old Andy, sitting beside me on the reserves’ bench, resting his legs. ‘Give me your radio.’ He passed it over with an expression that said, ‘Too late, why bother?’

‘Frank,’ I said urgently, ‘it’s Flea.’

Nearly ten seconds of the game ticked over while I waited for him to reply, and there just weren’t that many seconds left in the game.

‘Yes, Flea?’

‘Put me on. Please, boss.’

‘It’s over, Flea. The game is over.’ His voice sounded tired.

‘I know, boss. So do the Machetes. So they’re not likely to have a go at me, are they? There’re three minutes left. Put me on, just so I can tell my kids one day that I ran on to the field in a Grand Final.’ Another vital five seconds went by.

‘All right. It can’t do any harm. Get yourself ready. And don’t get yourself hurt.’

Twenty seconds later I was on the field. In the Grand Final. In front of eighty thousand people.

Fuller was getting ready to kick-off, but he noticed me and took his time, tipping me a wink as I ran into position. I tapped my chest and pointed to the far corner of the field. He shook his head. I gave him my best Crazy Jason glare and tapped my chest again twice. He glanced at Henry, who had seen me and was nodding his head at Fuller. Fuller shrugged and lined up for the kick.

I gave him the eagle sign, meaning ‘give it wings’. Kick it as far as you can.

He launched himself at the ball and gave it a whack it’ll never forget. The moment he started to run, I blinked into the Thing and was over the line in the same second that his boot hit the leather. The ball really did soar and, for a brief moment, I was afraid it was going to go dead on the fall, but it started to drop, just a couple of metres in from the Machetes’ goal line. Floridiana lined himself up to catch it. Like a true league professional his eyes never left the ball. Nor did he have any reason to take his eyes off it. There was no way any of the Warriors were going to get from the halfway mark down to the Machetes’ goal line in time to contest the ball.

Except for me of course.

The ball floated gently down into his arms, but, just before it got there, I leaped into the air, caught the ball, trotted the couple of remaining metres to the goal line and cruised around the back behind the posts to make it easier for the conversion.

Floridiana was still waiting there for the ball long after I had scored the try! Ainsley converted with ease and we were only ten points behind. With one minute and fifty seconds left on the clock.

The second try was even easier. Longer, easier, and a lot more dangerous. Brownie came up to me while the Machetes were setting up for kick-off.

‘Flea,’ he said with a voice full of concern. ‘Watch yourself. I overheard a couple of the Machetes. They’re talking about a Flea sandwich.’ Brownie trotted back into position, leaving me nervous and a little bit shocked.

The commentators called it a gang-tackle. Henry called it a sandwich. It wasn’t quite illegal, as long as it wasn’t late, or high, but it was definitely nasty. Two or three of the opposition try to hit you at the same time from different directions. They don’t care about making the tackle, just about hitting you as hard as they can. If you’re the unlucky player, you become the meat in a very hard sandwich. If you’re lucky, you’ll just get winded. If you’re lucky!

The Machetes kicked off, another good, long kick, although they did have the wind behind them to make it easier. The ball actually crossed our goal line and Fuller took it in the in-goal area. He skipped forward a couple of paces and passed it out to Henry, expecting Henry to start one of his long bullocking runs.

Except Henry didn’t. He looked at me and I nodded. So Henry gave me the ball. I darted forward at the Machetes’ line. If it hadn’t been for the Thing I probably would never have seen the sandwich coming, and even so it was lucky that Brownie had warned me.

Nick and Alistair, two of the biggest, ugliest Machetes forwards were closing in. One from the left, one from the right. Their hands were down, a sure sign of a s

houlder charge. And the two of them meant that Brownie was right. It was a shoulder sandwich.

When you’re thirteen, running in the Grand Final, with the Thing to help you, you are full of confidence. At least I was. And, although I saw the sandwich coming, I was sure I could deal with it. So I didn’t change my course at all. I just ran straight into the looming trap.

Nick and Alistair were big and strong, but they were also fast. Nick was flying in from the left and Alistair was hurtling in from the right. They were zeroing in on to a target and that target was me. Five metres away, then four, three, two, one and I stopped dead in my tracks. It was one of my favourite tricks.

I stopped dead and Nick and Alistair crashed into where I would rightly have been if I had kept going. Except I wasn’t there, so they just crashed into each other. It was like a train wreck with arms and legs flailing everywhere, and the thud of the bodies colliding was so loud that I felt it like a thud on my chest. Then they bounced off each other leaving a lovely little hole in the defensive line, which I skipped through with a wonderful feeling of joy and adrenalin.

That left just Rumble Bean to beat, and he was easy. I ran to the left then stepped off my left foot and changed direction abruptly to the right. Bean was expecting that, though, and stepped off his own foot, changing direction with me. But I had been expecting that too, and my left foot step was only a feint. I kept going to the left, and Bean was totally wrong-footed. He had one leg going one way and the other leg going the other way and his hand went down on the ground behind him. He looked exactly like he was playing a game of twister with himself!

Give him credit though. He was up in a flash and chasing hard. I didn’t run too fast. I wanted to keep it interesting for the punters, and I suppose a part of me wanted to show off and annoy Bean a little. So I kept just ahead of him, just out of range of his arms, or a diving ankle-tap. And like that the two of us ran down to the Machetes’ goal line.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

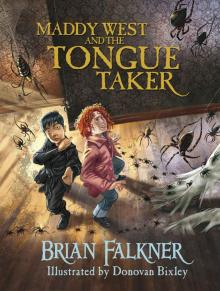

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker