- Home

- Brian Falkner

Task Force Page 9

Task Force Read online

Page 9

And while she was trying to contact SONRAD, a call had come in from a restaurant owner. Nanzi, one of her staff, had put it through.

It had been alarming, to say the least. The restaurateur had been heading home when he had noticed something odd in the river. Whatever it was, it had worried him enough to call the Coastal Defense Command.

Her office was only a five-minute walk from one of the bridges that spanned the river, and Kriz had arranged to meet him there. There were too many strange things going on. She was sure that something was seriously wrong, if only she could put her finger on what it was.

Asking Nanzi to cover for her for a few minutes, she checked that her phone was working, worried that the power outage might have affected the phone network. She dialed Nanzi’s phone and was relieved to hear the sound of ringing. The cellular system they had inherited from the humans operated on its own backup power supply.

She drew a sidearm and a set of night-vision goggles from the armory and set off for the bridge.

The T-board hummed under Chisnall’s feet, his speed steady at twenty miles per hour, according to the GPS on his wrist computer. His coil-gun was holstered on his back, and his Puke spray was ready on his utility belt. He scanned the buildings on both sides of the river, watching for any sign of life, for any interest in the river.

A vehicle turned a corner, spotlighting the team for a moment—like escaping prisoners against the wall of a jail—before sweeping on. Traffic was otherwise light, pedestrians were few, and the buildings around them were silent and still. Even so, Chisnall had the sense that a thousand eyes, in a thousand darkened windows, were staring at the river.

“This is really creepy,” Wilton said in an eerie echo of Chisnall’s thoughts.

“You got that right,” Price said.

“Meh, this is nothing,” the Tsar said.

“Here we go,” Price said.

“In Japan we had to recon through dense forest,” the Tsar said. “There could have been an ambush behind every tree, a booby trap under every step.”

“Gosh, that sounds dangerous. Did you survive?” Barnard asked, wide-eyed.

The Tsar ignored her. “What I did then, and what I’m doing now, is to focus every sense. I’m listening, noticing even the tiniest sound. I’m smelling things. My eyes are scanning every object in my vicinity, evaluating it as a possible threat.”

“And I guess the scope helps,” Price said.

“I can smell something right now,” Barnard said. “Bull.”

Again, the Tsar didn’t rise to the bait. “Try it,” he said.

“Oh, I’m trying,” Price said. “I’m listening as hard as I can, but all I can hear is you yapping.”

The Tsar was silent at that, and for all their scorn, Chisnall found the Tsar was right. Once you were aware of it, the air was full of sound. The sound of truck engines reverberating off city blocks. The dull burr of the task force beneath the waters of the river. Overhead, the harsh caws of parakeets and crows and the screech of fruit bats. There were smells too. More than he had realized. This close to the river there was an odor of muddy water, tinged with decay.

The Tsar didn’t stay silent for long. “There was one time—”

“Shut up, Tsar,” the others said in unison.

The concrete path they were following took a sharp turn away from the river. Ahead of them was a grassy park, dotted with shrubs. Chisnall led the way into the park, wanting to stay by the river’s edge.

Bzadians didn’t celebrate the human New Year, but the two Bzadian teenagers here were locked in a celebration all of their own.

Chisnall’s rifle leaped into his arms at the sight of two figures appearing from a dip in the ground, seemingly from nowhere, but he relaxed and reholstered it as the two, awkward and embarrassed, tried to rearrange their clothing and act as though they were just out for an evening stroll.

Chisnall sent them on their way with a short admonition, reflecting that a lot of human kids in the Free Territories were probably up to much the same thing that night. The young Bzadian female giggled as they disappeared into the nearby streets, hand in hand, and for a moment Chisnall felt even more keenly the weight that was pressing on his shoulders.

“How sweet,” the Tsar said.

“Not when they’re Pukes,” Wilton said.

“Even when they’re Pukes,” the Tsar said.

Barnard snorted.

“Never been in love, huh, Barnard?” the Tsar said.

“Love?” Barnard said. “No such thing. It’s merely a convenience for society.”

“You’d make a good Bzadian,” Price said. “That’s how they think.”

“Don’t worry, Barnard, there’s still time for you,” the Tsar said. “There’s still hope.”

“Not with you there’s not,” Barnard said.

“We’ve got a tail,” Wilton said as they emerged from the park back onto pavement.

Chisnall looked around to see a dog running along behind them in the middle of the roadway.

“Well, it’s got a tail,” Wilton said. He slowed and extended a hand back to it. “Nice, doggie.”

The dog growled, a deep, feral sound.

“Or not,” Wilton said, increasing his speed.

The dog could have been a Labrador but had longish fur. Maybe a mixed breed, Chisnall thought. It had gentle eyes, completely at odds with the harsh growl it had given Wilton. It ran beside them, tongue hanging out of its mouth as they rolled along the roadway, but disappeared as they veered onto a bike path that followed the riverbank.

Chisnall stared down at the river. The task force was a dark mass, shrouded by the man-made mist, which persisted, despite the indecisive breeze tearing short-lived holes in it. Only the turrets of the vehicles protruded out of the water, black against the black of the river, and with its blanket of mist, the fleet was very difficult to detect unless you knew it was there.

“See how clean the streets are?” Price said.

Chisnall hadn’t noticed until Price pointed it out. “No litter,” he said.

“No chewing gum,” Price said.

“Yeah, and I bet they always signal their turns and wash their hands after they sneeze,” the Tsar said. “They’d be real nice folk if they hadn’t started a war.”

“Did they?” Barnard asked.

“Did they what?” the Tsar asked.

“Start the war,” Barnard said.

“What do you mean?” Wilton asked. “Everybody knows what happened in 2020.”

“Don’t believe everything you read in books,” Barnard said.

“Dog’s back,” Wilton said.

This time it was in front of them, having taken some secret shortcut that maybe only dogs knew. It sat in the middle of the bike path and didn’t move as they approached.

They slowed.

The dog growled, that same low vicious sound from the back of its throat.

“Everybody hold up,” Chisnall said. There was little choice. The dog stood, blocking the path, its ears back, its teeth bared.

Wilton hopped off his T-board and advanced slowly toward the animal. “Good boy,” he said in English. “Good boy.”

“Don’t use English,” Chisnall said.

The dog let him get within about five feet before lunging forward, snarling, only backing off as Wilton’s coil-gun swung over his shoulder into his hands.

Chisnall found his own weapon in his hands. He hadn’t realized he had hit the release. The action had become instinctive.

Wilton backed away. “I don’t think it likes me,” he said.

Strings of drool hung from the dog’s jowls as it bared its teeth even more, refusing to give ground.

“I don’t think it likes any of us,” the Tsar said.

“It’s probably never smelled a human before,” Barnard said.

“Shoot it,” Price said.

“With a puffer?” Wilton asked.

“Is just a dog,” Monster said. “Leave him alone.”

<

br /> “It’s not a him,” Barnard said. “It’s a girl.”

“Gotta do something,” Chisnall said. “It’s going to draw attention to us.”

He glanced up at the apartment windows that overlooked the path.

“Is just being dog,” Monster said. He walked past Wilton, unhooking his coil-gun as he went. He held the gun out with both hands, barrel first.

The dog snarled and barked as he approached.

“I got a couple of vehicles on the scope, coming this way,” the Tsar said. “Could be a security patrol.”

“Shut the bloody thing up,” Price said. “Or I’ll do it.” She drew her knife.

“Don’t touch the dog,” Monster said. “Is beautiful animal.”

“And it’s in our way,” Price said.

“Don’t touch the dog!” Monster raised his voice.

It was the first time Chisnall had ever seen him angry. Price hesitated but sheathed her knife. “Then hurry the puke up,” she said.

Monster advanced on the dog. It half lunged at him a couple of times but pulled back as he kept the barrel of the weapon in between them.

Slowly, he moved forward, forcing the dog off to the side of the bike path. “Now go,” he said to Chisnall with a jerk of his head. He kept the dog trapped against the railing until the others were past, then backed away.

The dog followed, snarling and growling but not attacking.

“What’s the story with that patrol?” Chisnall asked.

“Heading away from us for now,” the Tsar said. “They’re following the highway east along the river.”

“Okay, keep moving. Maybe that mutt will give up and go find something else to do.”

Glancing at the river, he saw that the mist that blanketed the Task Force had not yet reached this point. “Everybody hold here for two mikes,” he said. “Give the Task Force a chance to catch up.”

The dog stopped when they stopped, maintaining a careful distance.

Without warning, Barnard, just in front of Chisnall, dropped to one knee and released her weapon. She scanned a high balcony through the telescopic sight. Chisnall trained his own sight on the balcony but could see no movement.

Barnard stood and reholstered her weapon. All without a word.

“See something?” Chisnall asked.

“It was nothing. Just some clothes,” she said.

“You’re sure?”

“Yeah.”

“What did you mean before about thinking like Pukes?” he asked.

“It doesn’t matter,” Barnard said.

“It might,” Chisnall said.

His last sergeant, Holly Brogan, had understood how Bzadians thought. A little too well.

Barnard shrugged. “They don’t think like us. We can’t beat them if we don’t understand them.”

Chisnall said, “We can’t beat them if we don’t have the right strategy.”

“That’s what I’m saying,” Barnard said. “Strategy is psychology.”

“And you’ve studied strategy?” the Tsar asked.

“No, but I’ve studied psychology,” Barnard said. “We keep using strategies and tactics that have worked against humans. If we thought like Pukes, this war would already be over.”

“I suppose you understand the way they think,” Price said.

“Better than most,” Barnard said.

“How do you mean?” Wilton asked. “How is strategy like psychology?”

“Strategy is the art of outthinking the enemy by understanding how they will react,” Barnard said.

“Like how?” Wilton asked.

“Like the Second World War …” Barnard paused and looked back at Wilton. “You have heard of the Second World War?”

Wilton flipped her the bird.

“Just checking,” Barnard said. “In 1940, Britain was on the verge of defeat. Hitler wanted to invade but couldn’t because of the RAF, the Royal Air Force. So he told the Luftwaffe to bomb the RAF out of existence. It almost worked. A few more weeks and Britain would have had no effective air force.”

“So why didn’t Hitler finish them off?” Price asked.

“Psychology,” Barnard said. “Churchill, Britain’s leader at the time, ordered bombing raids on Berlin. Hitler was enraged. He ordered the Luftwaffe to attack British cities in retaliation. The airfields were left alone. The RAF was able to recover. The invasion of Britain was delayed and eventually canceled.”

“But because of Churchill’s decision,” Chisnall said, “hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed.”

“Strategies have consequences,” Barnard said. “Churchill did what he had to do.”

He did what he had to do, Chisnall thought. Or was that just a phrase for avoiding the blame for something terrible? Like Uluru?

“What if you had to make a decision like that, and it meant that all of us would get killed?” Price asked. “Would you do it?”

“Of course. I wouldn’t even have to think about it,” Barnard said.

“You’re no fun,” Wilton said.

“What about you, LT?” Barnard said.

She was watching him. Evaluating him. Her eyes were focused like laser beams, cutting through any defenses, seeing right inside him.

“I’d do whatever it took to get the job done,” he said, and wondered if it was true.

A round of furious barking from the dog brought movement in a second-story window. Chisnall’s hand strayed to his gun release.

“Anybody got eyes on the gray building at two o’clock?” he asked. “Second floor, window to the right.”

“Female with a baby,” Wilton replied immediately. “I’ve been watching them since we stopped.”

“Okay, take it easy,” he said. “Only take her down if you absolutely have to. We don’t want her dropping the baby.”

“I don’t think she’s noticed us,” Wilton said. “The baby seems upset. I think she’s just trying to calm it down.”

Even so, they remained a moment until the Bzadian female disappeared from the window.

“Whatever it takes, huh, Chisnall?” Barnard said.

Chisnall said nothing.

“That patrol has turned around,” the Tsar said. “Now heading west, coming this way.”

“Okay. We need to get out of sight,” Chisnall said.

“There’s a patch of trees up here on the right,” Wilton said. “Just past the bridge.”

“How long have we got, Tsar?” Chisnall asked.

“A couple of minutes,” the Tsar said.

The trees were on the bank of the river, below the bike path. To get to them they had to climb the low fence of the bike path and jump down to the ground. The trees were thick and leafy, providing ample protection from view.

The dog, however, stopped, right alongside their position, and began to bark at them through the railings of the fence.

“Somebody shut that dog up,” Chisnall said.

The dog was barking madly now, lunging against the railings.

“I’ll do it,” Price said.

“No, I do it,” Monster said. “She will listen to me.”

“Sixty seconds,” the Tsar said.

A low growling came from Monster’s throat and the dog stopped barking as it pondered this new development.

“Just as well he speaks its language,” Wilton said.

“They’re probably related,” Price said.

Monster reached up to the fence and hauled himself back up onto the bike path. The dog backed away as he approached, then started barking again, louder and louder.

“Thirty seconds,” the Tsar said.

“Shut that mutt up,” Chisnall said.

“Shhh,” Monster said. He advanced, and the dog retreated, jumping and growling. They moved out of sight.

“Shhh.” They heard Monster’s voice gently now on the comm. “Shhh.”

The dog barked again, then stopped.

“Shhh,” Monster said.

After that there was silence.

/>

“How’d he do that?” Barnard asked.

Chisnall smiled. “He loves animals. He has a real way with them.”

“Patrol’s right on us,” the Tsar said, and they all heard the engine of the Land Rover as it passed along the highway on the other side of the trees. Almost as quickly, it was gone, the sound fading into the distance.

They waited for Monster, who appeared a moment later, not up on the bike path, but through the trees, from the bank of the river.

“Where’s the dog?” Chisnall asked.

“Gone,” Monster said. “Gone home. I think.”

There was something hard in his eyes.

“What did you do?” Chisnall asked quietly.

Barnard snorted. “What do you think he did?”

“Monster?” Chisnall asked.

Monster was silent, unmoving.

“He wouldn’t have hurt the dog,” Chisnall said. “Would you, Monster?”

“Of course not,” Monster said.

“Of course not,” Chisnall said. “Now let’s get out of here before the task force gets too far ahead of us.”

11. MAN DOWN

[0135 hours local time]

[Bzadian Coastal Defense Command, Brisbane, New Bzadia]

ON THE ROAD TO THE BRIDGE, KRIZ STOPPED AND STARED at the river. Her NV goggles revealed a low, dense mist. Something seemed odd about the river. The restaurateur had mentioned boats on the phone, but she couldn’t see any, unless they were very low in the water.

Then it clicked. The mist was what was odd. There was often a mist on the surface of the river, but that was in winter, when cold air reacted with warmer water. In summer, a mist was unusual, if not impossible, she thought.

A slight movement of the mist revealed a flicker of a dark shadow. Or was that just her imagination, coloring in the outline that the restaurateur had given her?

Intrigued, and more than a little alarmed, she continued to walk toward the bridge. Despite the recent odd occurrences, she could not bring herself to believe this was some kind of enemy activity. The radar and sonar feeds from the SONRAD station were still fully operational. They would have picked up any enemy forces the moment they entered the bay, well before they got anywhere near the river. The power blackout, however, was a worrying coincidence. She checked the time as she took her first step onto the bridge so she could log it later. It was 01:40 hours.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

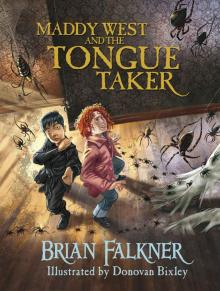

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker