- Home

- Brian Falkner

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Page 10

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Read online

Page 10

The Chinkana was on the outskirts of the city, about a fifteen minute moa-cart ride away.

I had not realised at first that Raki was not composed of a single level, but many, interconnected by shafts or kindril, which were climbed using a ladder. Not a ladder as I had ever seen one, but rather a central, strong pole, with cross-pieces regularly spaced down its length. The spacing, and the angle of the pole were such that people climbed up and down the ladders without using their hands, simply resting their knees against the next cross piece for balance, even if carrying quite heavy loads.

There were also long, angled ramps between levels and we rolled easily up one of these, marvelling at the power of the great bird beast that pulled our cart.

There were no doors in Raki (or anywhere in Ukhu Pacha as we later discovered) and we passed people eating, sleeping, bathing, children playing. In a training tunnel, which I recognised by the ragged walls and the dusty floor, I caught a brief glimpse of some young warrior-trainees practising the amazing wall-climbing skill we had seen during the battle in the tunnel. Not quite as adept at it as those we had seen, a couple of them made it nearly half way around the tunnel wall before falling, landing lithely on their feet.

Tukuyrikuq caught my expression.

‘Pana-Lloque, the ultimate quest for any young warrior. The ‘left-side/right-side of the path’. ‘There is a much deeper meaning here than you might think. To become a wall-walker a young warrior must master Pana-Lloque. Pana the right hand side of the mystical path. The cold, rational, objective and structured side of the path. Lloque, the left hand side: the spiritual, magical side. Only when a warrior has completed the inner circle of Pana-Lloque can he complete the outer circle of the tunnel. Then he is revered as a wall-walker.’

‘Why?’ Phil asked, who had not seen the terrifying wall-walkers in action.

Tukuyrikuq explained briefly. ‘Battles are most often fought in tunnels, but tunnels are often narrow and only the first few warriors can bring their knives to bear. Wall-walkers run not just around the circumference of the tunnel, but forwards, so that they land on the other side of the enemy, and we are able to attack from two directions at once.’ He nodded sagely, ‘The greatest of all wall-walkers are able to fight even as they run.’

How that must terrify the Maeroero, I thought, seemingly weightless warriors, attacking from the roof of the cave.

‘Do the Maeroero have wall-walkers?’ Jason asked.

‘No. We say it is because they cannot complete the inner circle. They cannot master Pana-Lloque. However there are a few among the Runa-Huri.’

‘Runa-Huri?’

‘Outcasts, Runa who have become filled with hoocha, or heavy-energy. They follow a leader who fights alongside the Maeroero.’ Tukuyrikuq’s voice shook as he forced the name out through spittled lips, ‘Bahdkina.’ He was silent after that for a while, as if the sheer effort of saying the name had exhausted him. There was more to be said here, I was certain, but it was not forthcoming.

As we left the centre of the city we passed through, first a farming region, passing great caverns filled with rows and rows of hydroponic channels, growing all manner of plants for food and fibre. Beyond the hydroponic farms was an industrial area. The Runa seemed quite structured in their town planning.

One of the first factories we passed had rows and rows of small silver blades laid out on reed mats, workers at the rear were sharpening more on spinning discs like grinding wheels. I remembered the strange weapon the warriors had carried on their backs.

As we passed through the main nan of the industrial area we saw a curious machine being repaired in a large, well-lit cave. There was an obvious seat of some kind for a driver, and at the front were two curiously circular plates, mounted on long, sturdy spindles, inset with literally thousands of diamonds.

Phil asked incuriously what the machine was.

‘Huinock Rumi Mikhuy, the Rock Eater. Machines such as this made the great Nans, and the Chinkana as well.

My ears perked up at the sound of a Rock Eater, clearly some kind of tunnelling machine. But the answer had raised all sorts of questions and Tukuyrikuq dealt with them as rapidly as he could.

‘When the spinning discs are at speed the Mikhuy will eat all rock, even the Jiwaya, the hard rock. I don’t know the word in English.’

‘Probably hematite,’ Jenny murmured, and I wondered how she knew.

‘It will eat the length of a man in about ten minutes, depending on the kind of rock. It digests the rock and excretes it as dust, which the Runa spread along the outer tunnels.’

We had seen far too much of that dust in the last few days.

‘To dispose of it?’ Phil asked.

Tukuyrikuq shook his head, but it was Jason who answered, with a look of understanding.

‘No, to track the movements of the Maeroero.’

‘To track all travellers,’ said Tukuyrikuq. ‘The Runa are expert at reading the dust. It is said that if a bat flies over the tunnel dust a Runa warrior will be able to tell when it flew, what kind of bat it was, and what it last ate.’

He smiled, ‘The Maeroero try to cover their tracks as they pass. But they are clumsy, oafish creatures and a well-trained warrior will look at the marks of their passage and tell you how many Maeroero there were and what speed they were travelling.’

‘Can the Huinock Rumi Mikhuy tunnel upwards?’ Jenny asked intelligently, making a good fist of the Runa Simi words.

‘Technically yes, and often necessary, but it is forbidden by a few of the gods, including Pachamama herself. When building a city it cannot be helped, but it is strictly controlled. To tunnel upwards, remember, is to journey closer to Kay-Pacha. Closer to Hell.’

Tukuyrikuq was going to elaborate on that a little more, and I would have liked to hear what he had to say, but he was interrupted by Phil, doing his best sixty-minutes interview style,

‘What is its power source?’

‘Steam, heated by burning gas.’

The conversation stopped then, interrupted by our arrival at the Chinkana platform. Another cart pulled up behind us and Turiz stepped off, followed by five more warriors, dressed in the ceremonial uniform of the Kuimata, the elite Guard.

The platform was a wide cave, with an unusually high roof. Not so high that I could not reach up and touch it if I had wanted, however.

Merchants lined the walls of the cave, waving their wares at us from small alcoves. We were offered everything from food (eels, moa eggs, cave wetas) to clothes, and a variety of kinds of reed, for what purpose I did not know, and many kinds of crystal.

Crystals seemed to be a primary industry in Raki and the price varied according to colour, rarity and function.

There were the common shili crystals that gave off light when warmed. The personal shili were warmed by body heat, and the long stretches of roof-shili by small gas-fired heaters in the centre. Light, itself, was a commodity in Ukhu Pacha, and I marvelled at how freely abundant it was on the surface, and how little thought we gave the miracle that really was.

There were crystals for health, along with tuning rods that made the crystals resonate. The point of this escaped me, but they were a popular item. Fire crystals were amazing, a translucent crystal, the depths of which seemed to quiver with an inner fire. I didn’t know what they were for.

But most precious of all were the rare black crystals, which seemed to have a value beyond that of gold or diamonds.

The platform was crowded but Turiz and the other guards cleared a way for us and escorted us to the front of the queues. There was a deep respect for the Kuimata from the populace, bordering on reverence. I hoped I hadn’t misread it, I hoped it wasn’t fear.

The travellers, and there were many, had a haunted, desperate look that I had seen before. They clutched reed bags overstuffed with belongings, even the small children.

A few months earlier I had been to a photographic exhibition highlighting the plight and the flight south of Vietnamese refugees in 1

962. It struck me that the expressions, the haunted eyes, were the same. These people were refugees. It was a deeply affecting moment and Jenny must have felt it too, the fear, the pathos, for she gripped my arm tightly with both hands.

I was self-centred, and churlish enough to feel a small smug glow of satisfaction that it was my arm she instinctively grasped, not Phil’s, although he was on the other side of her.

Tukuyrikuq must have read both our minds and said, ‘They seek haven in the Walled City. They seek …’ his last word was drowned out by a terrific whoosh as the Chinkana arrived, but I think he said ‘sanctuary’.

The entrance to the Chinkana was a long sliding door, curved vertically, less than a metre high, and I hoped that wasn’t an indication of the height of the Chinkana itself.

It was. The train was just over a metre and a half in diameter. I was about to question Tukuyrikuq about the small size but realised that drilling a small hole through hundreds of miles of solid rock is much easier than drilling a large hole! If I remembered my basic math right, doubling the size of the hole would quadruple the amount of rock dust to be removed. When the arriving passengers had disembarked Tukuyrikuq led the way onto the carriage. We ducked under the doorway, and crawled onto the Chinkana. There were no seats, just padded backrests, arranged in facing pairs, two on one side of an aisle and one on the other. The arrangement meant we could sit as a group, which was a pleasant surprise. It also meant that Tukuyrikuq and the guards had to sit in the area behind us, and that gave us our first chance for a private chat since we had been captured by the warriors in the tunnel.

Historians now regard the conversation that took place that day on the Chinkana as a ‘significant event’. The first of our great ‘Councils of War’ as they came to be known. But to us, it seemed nothing more than a group of friends chatting on a train, albeit under quite bizarre circumstances.

‘The first question,’ said Jason, ‘Is how do we get out of here?’

I nodded, ‘Before the war.’

‘Before the Amatuas,’ Fizzer said chillingly.

Jenny said ‘I think a better question would be, where the hell are we?’

We all pondered that for a moment.

‘We started at Mangapu,’ Jason said, ‘We travelled a long way, but mostly down. We can’t be far from there.’

‘But in which direction,’ asked Jenny.

I shook my head. With all the twists and turns I had no idea.

‘East,’ said Fizzer. ‘We went mainly East.’

‘How you could know that?’ Phil’s question carried a sneer.

Fizzer shrugged, and as nobody had a different opinion, and as Fizzer was often right about odd things, we decided we had gone East.

‘Towards Rotorua,’ I said, which might explain some of the thermal activity.

Phil said, ‘So we know where we are, or we think we do. Now, how do we get out of here?’

There were no immediate answers.

‘Old Tuku doesn’t know, and he’s been looking for 80 years,’ Phil expostulated.

‘How does air get in and out?’ Jenny Brainy Jenny asked thoughtfully.

That raised a few eyebrows.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, unhelpfully.

‘We should ask Tukuyrikuq,’ Jason said. ‘He must have given that some thought.’

‘Maybe we’re not meant to escape,’ Fizzer said. ‘Maybe we’ve been brought here for a reason.’

‘We weren’t “brought here” at all,’ Phil snarled. ‘We ran away from an earthquake.’

The way he said it was like a criticism of Jason, as if anyone with any guts would have stayed and slugged it out with hundreds of tonnes of falling rock. Phil could be a real jerk, I thought.

‘We can’t stay,’ I said. ‘We don’t want to be caught in the middle of a war.’

‘We won’t be,’ Jenny said brightly, ‘If the Amatuas kill us all first.’

‘So we need to get out of here.’ Jason said. It seemed like we were talking in circles. ‘What do we know about this place?’

Jenny answered, as if she had been considering this question, ‘Some of their technology is highly advanced, like the Chinkana and the Rock Eaters, and yet in some areas it is quite primitive.’

‘No electricity,’ I said. ‘They have no electricity, so no electronics. No computers, radio communications …’

‘TV, Playstation,’ Fizzer contributed with a grin.

‘No lightning,’ Jenny said.

We all looked at her.

‘No weather, no thunderstorms, no lightning,’ she said. ‘That’s how electricity was discovered, Ben Franklin flew a kite in a thunderstorm.’

Fizzer whistled softly. ‘For want of a kite …’

Phil asked, ‘What else have they missed?’

‘There’ll be lots of medicines,’ Jenny considered, the med-student-to-be. ‘Drugs made from plants that can’t be grown underground.’

‘Gunpowder,’ Fizzer said quietly, and we all nodded, never realising the significance, the prescience of what he had said.

‘Without gunpowder and electricity they are effectively living in a medieval society,’ Jason said.

‘Does anyone have any idea what this war is all about?’ I asked. ‘I mean, is it a territorial thing?’

‘Maybe a religious thing?’ Fizzer postulated. ‘More people have died, above ground I mean, in the name of one god or another than for any other reason except natural causes.’

‘At least we’re on the right side,’ I smiled.

‘How do you know?’ It was Phil. ‘No, seriously guys. I am not just trying to be negative. How do you know that the Maeroero aren’t the good guys here?’

It was a good question. Phil carried on.

‘Just because the Runa found us first, doesn’t necessarily make them all saints.’

‘They’ve treated us well,’ Jason started.

‘Sure. They challenged you to a fight to the death, and might well finish the job when we meet the Amatuas.’

It went against my feelings about these people, but he had a point. I had to admit it. How did we know?

‘Who, or what, are the Maeroero anyway?’ There was a deeper point to Jenny’s question than it appeared, but it escaped me what it was.

‘I have a theory about that,’ said Fizzer, and stopped, marshalling his thoughts. We waited.

‘Underground people,’ he said at last.

Phil scoffed, ‘That’s your theory?’

‘No wait. I wonder if the Runa people are surface dwellers, like ourselves, who for one reason or another have chosen to live underground. I mean so far in the distant past that they have long forgotten that they ever came from the surface.’

‘It’s possible,’ mused Jenny. Phil shook his head.

Fizzer said slowly, ‘But what if the Maeroero are a different race altogether. Primates like ourselves, but branch that actually evolved underground.’

Jason said, ‘Throughout Northern Europe they have myths and legends about trolls: hairy creatures that live in caves. Legends often have a factual basis.’

Jenny said, ‘In North American the legends are of the Sasquatch, or Bigfoot. In the Himalayas it’s the Yeti, or the Abominable Snowman.’

I said, ‘The Sasquatch is supposed to be nine feet tall. The Maeroero weren’t that big.’

‘Legends have a way of getting exaggerated,’ Fizzer said simply.

Phil laughed suddenly. ‘In 1960, Sir Edmund Hillary led an expedition to the Himalayas to search for evidence of the Yeti. Maybe he should have tried digging!’

We all laughed at that.

The seat backs were covered with the foamy mattress material and there was a square mat of the same to sit on. It was quite comfortable and the ride was silky smooth, yet I was suddenly feeling decidedly uncomfortable. The Chinkana began a sweeping left-hand turn, although I wasn’t quite sure how I knew that. The Chinkana tunnel, being a perfect circle, was also a perfect camber, and the centrifugal forc

e of the turn simply drew the vehicle higher and higher up the tunnel wall. Our centre of gravity was unchanged.

One thought kept returning to me. How did we know?

What if the Maeroero were some normally peace-loving race trying to reclaim their ancient homelands from foreign invaders. Pure conjecture, I know, but my point was that we didn’t know. We had dropped into this world through a hole in the roof. We were not part of it. We could not hope to understand the history and tribal rivalries. Nor did we have any right to interfere, not that we had any ability to interfere.

Somehow my mouth and my mind got muddled then, and I spoke my next thought out loud.

‘We’ve been blown around like a leaf in a windstorm up till now,’ I said without intending to. ‘It’s time we took control of our own fate.’

I was aware of the eyes of the others all directed at me. Phil was looking at me like I was retarded, and even Jason said gently, ‘That’s kind of what we are talking about.’

Only Fizzer understood, I saw from the small pursing of his lips and the surreptitious nod. Only Fizzer truly understood what my mind had just blurted out.

‘Tomorrow we’ll meet the Amatuas,’ Jason said presently. ‘We’ll fudge our way though that as best as we can, and try to find a way to escape before the war. Maybe we can hide out in the cave of mirrors for a while. No-one would look for us there.’

‘And eat what exactly?’ Phil snapped.

‘Calm down Phil,’ Jenny said softly, but he wasn’t finished.

‘No offence,’ Phil said, ‘But who made you the leader anyway?’

I could see all the old doubts and insecurities bubble back to the surface. Jason, the school dropout. Jason, the builder’s labourer. Jason the Uncoordinated. Jason the Dyslexic. Jason the Loser. A chill went through me as I saw the spark of a new human being extinguished in my friend, yet I said nothing. For once this was not the time for me to leap to his defence and I instinctively knew it. I would just be ‘sticking up for my friend’ and it wouldn’t satisfy Phil, nor help Jason.

So I sat there and watched the light go out in his eyes.

‘I was just trying to contribute; I didn’t mean to take over. You guys can sort out who is in charge,’ he didn’t look at any of us as he said it.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

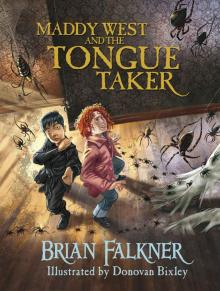

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker