- Home

- Brian Falkner

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Page 11

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Read online

Page 11

Jenny was silent too. I felt sorry for her, caught between her friends and her boyfriend, and I hated, as much as I admired, her loyalty to her man.

‘Actually, Phil, I think he’s doing a great job.’ The first time Tupai had spoken on the trip, and as usual, simple, direct, and to the point.

Phil argued, ‘We need a strong leader,’ obviously seeing himself as the prime contender.

Fizzer cut him off. ‘No offence Phil, but we need a leader who can make decisions, not just talk about them.’ He put his hand on Jason’s shoulder. ‘Jason, I’d follow you to the centre of the Earth.’

I couldn’t help noticing the small, secret smile that crossed Jenny’s face, and Jason’s back visibly straightened. He looked at me and I nodded. The light began to return.

‘You already have,’ Jason said with a quiet smile.

10. The Walled City

By Jason Kirk

The first thing we saw when we emerged from the Chinkana was a construction site, and that gave me an idea.

Flea had muttered something on the train about leaves blowing in the wind and he hadn’t thought anybody had got it, but I think I’d understood it more than he had realised. We needed to be proactive, not reactive. We needed to make things happen, not just respond to things that happened to us.

And I, as the newly, if not unanimously, elected leader, was the one who had to make it happen. I still wasn’t very comfortable with the leadership mantle, but at least I felt I now had a mandate from the team.

A few hundred yards from the Chinkana platform along a gently sloping tunnel, we passed an opening into a large cave. Two Rock-eaters sat idle and a cart, half-laden with rock dust sat nearby. The signs of work were all around, but there were no workmen, just two guards in battledress, carrying taiaqha.

‘Urin Bat Farm,’ Tukuyrikuq explained with more than a little pride as we passed. I suspected he had something to do with the planning of it. ‘It will be the greatest bat farm in all Ukhu Pacha when completed. For now construction has stopped, because of the raids. Soon the transporters will come to remove the mikhuy to a place of safety.’

He looked gravely at us, ‘Can you imagine the catastrophe should the Maeroero ever get their hands onto one of these? Cave-dogs!’ he spat on the ground, using a derogatory warrior’s term for the Maeroero. ‘With a Rock-Eater they could breach the great rock walls of Contisuyo and thereafter there would be no peace. Contisuyo is the gateway to all of Ukhu Pacha. They would attack and attack until all that was left of the Runa would be their blood, staining the wall and the floor of the Cave-dogs’ new home.’

‘Just two guards?’ I asked.

Tukuyrikuq nodded. ‘We can’t station a garrison at each site. Their job is to alert the local defence force should any Maeroero penetrate this deeply into Ukhu Pacha, and if all else fails, to destroy the mikhuy.

‘How,’ it was Fizzer that asked.

‘By jamming the release valve,’ Tukuyrikuq said grimly.

I shook my head. Flea also looked blank, but Jenny said, ‘Oh my god.’

It was annoying and yet wonderful the way she understood things so much faster than the rest of us sometimes.

‘They’d be killed,’ she said.

Tukuyrikuq nodded, ‘Along with any surrounding Maeroero, but the mikhuy would be destroyed. That is the important thing.’

Then I understood. Their job was to commit suicide by firing the boilers and jamming shut the steam release valve. Without possibility of escape, the pressure inside the great engine would be immense, and the resulting explosion catastrophic.

‘Have the Maeroero ever captured one?’ Daniel wanted to know.

‘Once. A troop of warrior-trainees got it back before they could do any damage. The troop had been exercising in the tunnels and were the closest warriors to the raiders.’ He smiled, ‘They were led by a young illoquy (the rank is roughly equivalent to lieutenant) who walked the wall and got between the cave-dogs and the rock-eater while his troop attacked from the rear.’

‘A bona-fide hero,’ Jason said. ‘Did he get a medal?’

‘No such thing in Ukhu Pacha. But he was promoted. He ended up as the head of Taytacha Raki’s guard unit.

‘Turiz!’ Flea and I said it together.

‘You were right not to take his life in Tupaq,’ the old man continued. ‘He is a valuable fighter.’

‘And a devoted believer,’ Jenny said.

‘Not quite as devoted as you might think.’

I looked up, so did Jenny, ‘But the way he prostrated himself after the Tupaq!’

Tukuyrikuq said, ‘We are not quite the simple people you might imagine. Turiz had been defeated by, as he put it, a child. The only was he could save face, retain his honour as a warrior, would be if Jason was in fact Pachacuteq.

‘But it wasn’t even Jason he was fighting!,’ Phil exclaimed. ‘When it came to the crunch it was Flea who stepped forward. How could they possibly believe Jason is this great Pachacuteq when he gets someone else to do his fighting for him.’

Phil was right, I thought, and I had not asked for the title. Phil had been increasingly truculent and I had seen more than a few sarcastic glances at me. I could only guess at the reason. Perhaps Phil saw himself as the natural leader of the group. Maybe he wanted to be the great Pachacuteq.

Tukuyrikuq shook his head though and he was emphatic. ‘No. You misunderstand the culture of my people, and you couldn’t be more wrong.’

Interesting, I thought, the way he had said my people.

Tukuyrikuq continued. ‘A champion is an accepted part of life for a ruler. This is a warrior culture. Survival of the fittest. Even a Taytacha can be challenged, but to prevent a great leader from spending his or her time and energy on wasteful Tupaq, all Taytacha choose their strongest warrior to be their champion. It does not diminish the ruler, far from it. It is always assumed that whatever skill and power the champion possesses, the ruler possesses more.’

He rubbed my head, quite affectionately, ‘If Pachacuteq’s child can defeat a warrior of the Kuimata, then what kind of fighter must Pachacuteq be!’

There was only one way into Contisuyo, the Walled City, and that was through a hole in the roof. Actually a series of holes in the roof, nine of them.

We arrived, with a throng of people, at a large cave with a ceiling at least ten metres high, even higher in places. It was an unexpected pleasure, accustomed as we had become to ducking and stooping under low roofs. It seemed somehow as if a weight had been lifted from our shoulders and I saw by the expressions on my friends’ faces that they, like myself, revelled in the feeling of release, of oppression lifted, that it gave us.

In the roof of the cave, spaced at irregular intervals in no particular pattern were nine holes, each large enough for, not one, but two of the pole ladders we had grown used to in the kindril, the vertical shafts, of Raki. One ladder, it appeared, was an up ladder, and the other down.

Tukuyrikuq pointed out the last two, more circular holes, as being man-made, to cope with the increased traffic over the years. The original seven holes were more ragged, although a couple had smoother areas where they looked to have been enlarged a little.

The flow through these holes was steady at the best of times but with the constant arrival of refugees, it was like rush hour. The refugees on the Chinkana were just the tip of the ice-berg I realised, and many more had journeyed here using the nans and natural cave passages. Several of the down ladders were acting as defacto up ladders to help cope with the flow.

Once again we were accorded VIP treatment and a path was cleared for us.

I found the single-poled ladder much harder to use than I had anticipated, watching the ease with which the Runa gliding up and down them. I couldn’t quite get my balance on the right points, and had to use my hands. For once, the others fared little better, only Fizzer was able to climb in the Runa hands-free style.

We emerged onto the floor of another high cave and the first thing I saw

were the giant Kepa stones. The next thing I noticed was the strong reed-rope that curled around the end of the ladder and up through a pulley system on the roof.

By each of the nine holes stood a small, flat-topped pyramid, a Kepa. Each about two metres high and inscribed, on each of its four faces, with hieroglyphics like those we had seen on the Gates of Hell.

From under each Kepa two stone railings emerged, embracing the hole by which the Kepa stood. Two guards stood by each stone, in a uniformed robe of a type we had not seen before.

Tukuyrikuq tried to explain a little as we made our way, with our guards, through the bustle leading to an opening in the wall of the cave.

‘They call this the “Walled” city, but the wall they refer to is the one you are standing on,’ I must have looked confused because he continued, ‘The Runa have no word for ceiling. Just one for a rock wall, Rumi. It can refer to the floor, roof, left, right, front or back wall. It is all the same to the Runa, they live in a three dimensional world.

The great Kepa stones, hewn by the ancients, some say by Pachacuteq himself, are the guardians of Contisuyo. Should the Maeroero attack the city itself the ladders are withdrawn …’ that explained the ropes and pulleys, ‘… and the Kepa stones are moved to cover the nine holes. Contisuyo becomes an impregnable fortress, a sanctuary, while the garrisons at Raki and Q’eros are mobilised to attack the invaders.’

‘What possible way do they have of moving those stones,’ Phil said sceptically. ‘They must weigh a ton!’

Many tonnes I thought.

Tukuyrikuq smiled. ‘The stones are weighted, and the rails are oiled, for easy movement. Each stone has its sacred guardians, two spiritual warriors whose only function is to close the Kepa stones in time of danger. They have not been closed for thirty years, by my best estimation, but I fear they will close again soon.’

I looked closely at the Kepa hole we had emerged from. The pyramid shaped stone was on the uphill side of the hole and there was a slight downward cant to the railings. Two warriors could move the great stone I decided, with a little help from gravity. How they opened them again was a matter for conjecture.

Two flat walls of the large cave, by the entrance, were carved with massive snakes heads. I had noticed the symbol before, in places in Raki, and painted on the side of the Rock-Eaters. I asked Tukuyrikuq what it meant.

‘It means Ukhu Pacha,’ he replied. ‘The world we live in. There are three worlds. Ukhu Pacha, the material world – what you would call the subterranean world – symbolised by the great serpent. Hanak Pacha, the spiritual world, and Kay-Pacha, Hell, symbolised by the Panther.’

Jenny was on that like a flash. ‘The panther! They have panthers here.’

Tukuyrikuq shook his head but did not say any more.

‘And this serpent,’ Jenny asked. ‘Do they have snakes here?’ It was a possibility that made all of us uncomfortable, coming from a country where there were no snakes. I thought I could see the point of Jenny’s question. There were no snakes above ground. If there were snakes below ground that would imply that the two worlds were shut off from each other so thoroughly that not even a snake could find a passage to the surface.

But Tukuyrikuq said, ‘Not a snake, a great serpent.’

‘Like an anaconda?’ Phil suggested, ‘A boa-constrictor?’

Tukuyrikuq smiled at that and shook his head, saying ‘Patience, my friends, you will meet the great serpent soon enough.’

And with that we passed through the opening in the great wall of the cave, and into Contisuyo itself.

In many ways Contisuyo was similar to Raki, but there were important differences. The first, most noticeable were the people. While Raki had been a predominantly Amori city, the ratio between the two races here was reversed. The majority of the people were mixes, a little of one, a little of another, but of the pure-blooded Amori there were few, while the Runa were everywhere.

The second clear difference was in the walls; I suppose you would say the architecture. In Raki the walls had been bare rock, sometimes painted. In Contisuyo the prevailing fashion seemed to be plaster. Most of the walls had a smooth look and texture that came from a coating of a substance that there was no English word for, but which Jenny eventually translated as “Plastirock”.

The third difference was size. Even from our short foray into its bustling nans it was clear that Raki was a mere bubble in comparison. Great long straight nans stretched into the distance, filled with people, moa-carts, merchants and more. When you reached the end of one of these huge nans and turned a corner, there was another, stretching for kilometres ahead of you.

Our cart stopped by a massive kindril, over thirty ladders climbing up a massive shaft. At the top, another level to the city, as big as the one below. Another kindril, another climb, and another level.

I lost count of the climbs on our journey to meet the king, but I am convinced it was at least thirty, plus on a number of other occasions we rolled up a huge, sloping, spiralling ramp without having to leave the moa-cart.

Jason said, after one of the climbs, ‘For a people that refuse to tunnel upwards, they’re not doing too badly.’

Jenny said thoughtfully, ‘The amount we have climbed in the last hour, we must be dangerously close to the surface by now.’

And we continued to climb.

It was Fizzer that worked it out, his intuition beating Jenny’s cognition by just a few seconds.

‘We’re inside a mountain,’ he said. ‘Ruapehu or Ngauruhoe at a guess.’

‘We can’t be!’ I was dumb-founded. ‘They are active volcanoes.’

‘He’s right,’ Jenny said. We’re inside a mountain. Not in the centre when the huge volcanic vent is, but on the outskirts of the mountain. The huge broad base of the mountain. We are inside a living volcano!’

The last few levels of the city grew smaller, as far as we could see, which made sense with the mountain theory. It was ironic, I thought, we so badly wanted to get back to the surface, and here we were above ground level, but no closer to home than before.

That was the thought that kept looping over and over in my brain as we were taken up a great flight of marble stairs into the royal palace to meet the king.

Tukuyrikuq spoke quietly to us as we entered the palace, ‘Do not expect to meet a buffoon like Taytacha-Raki. They are as different as rock is from water. The one thing they do have in common was the love and respect of their people.’

He explained that Taytacha-Raki was a local ruler, a governor, but Taytacha-Contisuyo is the Sapa, the king, of all Ukhu Pacha. King is probably the wrong word, as the Taytacha governed with a kind of benign benevolence. He guided his people; he didn’t command them. He made requests, not proclamations, and people responded to those requests with a fervour bordering on fanaticism. Taytacha has the connotation of father, and the Sapa-Taytacha, the supreme Taytacha, was the wisest father of all.

‘Runan society is infallibly polite to guests, it is one of the sacred laws,’ Tukuyrikuq said.

I thought of the Tupaq and wasn’t so sure.

‘When the Sapa speaks to you, you must seek out the meaning behind his polite words. What he does not say is far more important that what he does say.’

On that confusing and slightly disturbing note he fell silent as twelve physically imposing members of the King’s Kuimata flanked us and escorted to the King’s meeting room. Subtle body language passed between the Kuimata who had escorted us from Raki, and the Kuimata of the King, and I realised that an entire conversation had taken place between the two groups without a word being spoken. These soldiers, I was reminded once again, were trained to operate in the tunnels and caves of this world, where the slightest noise could bring death raining down on your troop.

Our Kuimata stayed by the entrance of the palace, as the others escorted us inside. Clearly the only warriors allowed within the palace were the King’s private and trusted guard. Once inside an atrium-like area, before we were allowed into the palace

itself, we were thoroughly searched for weapons. Even Tukuyrikuq.

Other soldiers keep guard from shadowy alcoves built into the walls, and in many places, high in the walls, were narrow slits. At first I took them for viewing slits, but then realised that they would offer a great vantage point from which to aim a blade-slinger, the weapon we had seen carried on the backs of the warriors.

The entire palace, as far as I could see, was made of marble, except for the high ceiling. The height of the ceiling – itself a sign of great wealth in this society where many called home a metre high cave – was made of the living fire crystals, great blocks of them, dancing and breathing their inner flame. Whatever the light source was, it was above the fire crystals, shining through them, broadcasting their beauty throughout the palace.

If the Sapa was trying to impress visitors, he was doing a good job.

There were no doors in Ukhu Pacha, not even on the meeting/planning room of the great King, Taytacha-Contisuyo, the Sapa Taytacha. But to protect the secrecy of the meetings that took place in the room we passed through no less than three walls, the openings of which were draped with heavy cloth that the Kuimata drew aside for us.

Inside we met, for the first historic time, the great ruler of all Ukhu Pacha.

Tukuyrikuq was right about the difference, I thought, they were like night and day, although that was a concept that I wouldn’t have liked to try to explain to them. The Sapa was a slim, powerfully built man with a face that radiated wisdom and power. He had a presence that filled the room despite the twelve or so other people standing there.

Yet there were laugh lines at the corners of his eyes and the smile that came to his lips as he greeted us was a ready, and a genuine one I thought.

The front half of his head was shaven like that of his warriors, and I thought that he had probably been a warrior himself. A warrior-king. That was a man whose people would respect and trust him.

The four men closest to the King were the Apu’s, we learned later. The heads of the four branches of the military. Felipillo, the closest, was responsible for the Kuimata, a boyhood companion of the king, and his most trusted friend. Under his jurisdiction fell the protection of the Sapa, the other Taytachi, and certain nobles who warranted the protection of the elite guard.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

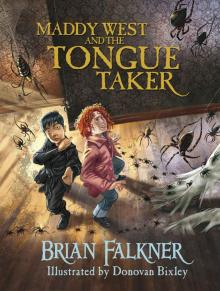

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker