- Home

- Brian Falkner

Clash of Empires Page 22

Clash of Empires Read online

Page 22

Frost finishes and Blücher lowers his head, glowering at them from beneath bushy eyebrows.

“You think me foolish enough to take on battlesaurs?”

“With luck they will be dead,” Frost says.

Blücher nods. “My spies have heard stories that your men have indeed escaped. So perhaps, with luck, cunning, and courage, they will be able to complete their mission. But what about the rest of the French dinosaurs? In the cave beneath the Sonian? Or do you expect me to attack the abbey also? If so, I must teach you a lesson about fighting a battle in a forest, where artillery is useless, especially in a forest protected by creatures that are most at home among the trees.”

“This matter was also of grave concern to the Duke of Wellington,” Frost says. “So much so that he tasked Willem and myself with the job of sealing the entrance to the cave, to ensure that no other battlesaurs are brought into the battle.”

Blücher laughs again. “Now I see why you are not afraid of Napoléon. How you held your nerve on the battlefield and brought down a battlesaur. You have an old heart for a young man.”

“Thank you, Excellency,” Frost says.

“But my answer is no,” Blücher says. “Even without battlesaurs Napoléon is a formidable enemy. His Grande Armée is bolstered by the Dutch, the Bavarians, and the Italians. It is a battle I fear I could not win.”

“You would not have to win it,” Frost says. “You may not even have to fight it. Just the presence of your army on the outskirts of Calais would be enough to force Napoléon to delay the invasion. He knows your reputation.”

“That is true,” Blücher says. “But Napoléon is no fool. He would call my bluff and bring the battle to me. I would have to withdraw and the repercussions against Prussia for breaking the alliance would be savage.”

“Your Excellency,” Frost begins, but he is stopped by a raised hand from Blücher.

“I must decline your offer and my answer is final,” he says.

“And what if Napoléon was dead?” A familiar voice comes from the doorway and Willem looks up to see Arbuckle, his hands bound, escorted into the room by two Jägers, swords at the ready. He is almost unrecognizable. His face is a mask of dried blood and his clothes are bloodied and torn. He is limping.

“Captain Arbuckle,” Blücher says, rising. “I might have detected your hand behind all this.” He motions for Arbuckle’s hands to be untied. “A glass of brandy for this man.”

Willem is greatly surprised to learn that Arbuckle is alive, and somewhat less surprised to find that he knows Blücher personally.

As soon as his hands are free, Arbuckle salutes, and Blücher returns the salute, then takes Arbuckle’s hand and shakes it warmly.

“It is good to see you, you young rapscallion,” Blücher says.

“And you, you old scoundrel,” Arbuckle says. He turns to the others. “I apologize for my delay. I was held up somewhat after we were attacked at Antwerp.”

Willem looks again at the blood and the torn clothing. He thinks that Arbuckle’s “delay” has been a costly affair.

“What of the others?” Willem asks. “Jack and the saur-killers?”

“I know no more than you,” Arbuckle says. “I can only hope that they got away and are on their way to Calais.”

Brandy is duly poured and Arbuckle drains the glass in a single gulp.

“If Napoléon was dead, that would change everything,” Blücher says. “But the gods would not smile on us so brightly.”

“Perhaps the gods favor you more than you think,” Arbuckle says. “The emperor is indeed dead. Such is the word and it is spreading like flame in dry powder. I am surprised it has not yet reached your ears.”

Blücher looks startled and motions to an aide, who hurries out of the room.

“Is this one of your tricks?” Blücher asks.

“If I am wrong or right, you will find out soon enough,” Arbuckle says. “I am sure you have eyes of your own in Calais. But the man who told me believed it to be true.”

“Napoléon dead!” Blücher rises from behind his desk, crossing excitedly to a map pinned to the wall of the kitchen, if a big man of advanced years could be said to move excitedly. “If this is true, his army will be in turmoil. Forget the invasion. Bring your ships to Calais. The French Grande Armée would be a firebird without a head.”

“The army still has its battlesaurs,” Nostitz says. “And Thibault, who commands them.”

“And I will not send my men up against battlesaurs,” Blücher says. “But on the other hand, if your saur-slayers have succeeded, then there will be no better time to smash the Grande Armée.”

“You will know when you see the yellow rockets,” Arbuckle says.

Blücher ponders this a moment longer. “If the rumors are true, and Napoléon is dead, then I will move my army to Calais. If we see the yellow flares, then we will launch an attack.”

“And if not?” Frost asks.

“Then I will have no choice but to swear my loyalty to whoever now leads the French Army,” Blücher says. He turns to Nostitz. “Give the order. We move at first light.”

To Frost he says, “Wellington wanted you to seal the entrance to the cave. I am interested to know how you intend to do that.”

“It will not be easy,” Frost admits. “There are secret ways into the cave system. Willem and I have used them once before, but then we had a guide. A girl who had lived in the forest for a number of years. She came with us, but was separated from us when we were attacked.”

Blücher frowns. “A small, feisty girl? With very short hair? Looks like a boy?”

“Yes!” Willem cries. “That is Héloïse! What do you know of her?”

“I know that my guards will be very pleased if you take her off their hands,” Blücher says.

BREAK OUT

The brute, Private Deloque, comes to the door of the little church, blocking the meager sunlight that folds its way in through the thick trees of the forest and over the high stone walls of the abbey.

Cosette and Marie are mending uniforms for their captors. It is a choice, not a duty forced on them. Marie suggested it a few weeks earlier and Cosette agreed. It does not hurt to be on good terms with our captors, Marie had said.

And it passes the time.

They have been given needle and thread to do this, along with an old blunt pair of dressmaker’s scissors that Cosette has sharpened by unscrewing the blades and scraping them on the stone walls of the church. She has paid particular attention to the points of the scissors.

Marie and Cosette both look up when Deloque arrives at the doorway. Cosette shudders a little. Deloque always makes Cosette uncomfortable. His eyes linger on parts of her body where a gentleman’s eyes should never linger.

Today Deloque has a big dumb smile on his face. He grins stupidly at them for a moment, then turns to leave.

“Something is going on,” Marie comments quietly to Cosette.

“Private Deloque,” Cosette calls out.

Deloque looks back, but just grunts.

“Do you have something to tell us?” Marie asks.

“Nothing you will not find out soon enough,” Deloque says.

It is the most words Cosette has heard him string together in a single sentence.

Deloque turns again to leave.

“Don’t be silly,” Cosette says loudly. “If there was anything worth telling, they would not entrust it to someone as stupid as Deloque.”

Deloque turns back again and scowls. “I know things that nobody knows. They thinks I don’t listen but I do.”

Cosette turns to Marie. “I am not interested in what he has to say. Even if he did overhear something, I doubt he would have understood what he heard.”

“Laugh all you like,” Deloque says. “You won’t be laughing soon.”

“He knows nothing,” Cosette says.

Deloque sneers. “They found that boy,” he says. “They killed him.”

“What boy do you mean

?” Marie asks carefully.

“The one who killed the saur,” Deloque says, and he gives a short laugh.

Cosette is unable to breathe. Her heart seems to have jammed in her chest. Her feelings must show on her face and it makes Deloque grin.

“The one they all been looking for,” Deloque says. His words seem to be coming from far away. “He came back from England on a boat and they caught him and killed him. Put his body on a cart and paraded it through Paris.”

Now he is grinning broadly. Cosette forces a smile to mask the horror that she is feeling. “We don’t even know who that is,” she says.

Deloque laughs. “So you say,” he says. “I say different.”

His shape leaves the doorway, but Cosette can still see him outside, tending the plants in the central garden.

“Pray God that it not be true,” she says.

“Come,” Marie says. She seems distant. “We will talk as we walk.”

She gathers up the dressmaking tools and Cosette follows her out of the church.

“There are things to do,” she says.

“Madame, if the news is true, then your son is dead,” Cosette says, dumbfounded. “Do you not wish to mourn him?”

“Do I wish to mourn him?” Marie asks, without stopping or looking at Cosette. “Of course. But we have no time to mourn him.”

“What do you mean?” Cosette asks.

“If Willem is dead then so are we,” Marie says. “He was the only reason they kept us alive.”

“We are no danger to them,” Cosette says. “If Willem is dead they will have no reason to keep us here.”

“Foolish girl,” Marie says sharply, and in her tone Cosette finally hears the depths of her anguish. “We know what happened at Gaillemarde. We are witnesses.”

“We did not see it,” Cosette protests.

“We did not need to,” Marie says. “Thibault will never allow us to leave. Not alive. You must escape and it must be today.”

“But we can’t…” Cosette trails off, realizing what Marie has just said.

“Three of us cannot make it,” Marie says. “Cosette, you must take your bath today, and slip away. If François is there he will help you.”

“We must all escape,” Cosette says.

“That is not possible,” Marie says. “You must go.”

“No,” Cosette says. She turns back. “Private Deloque,” she says, and her voice is strong and formal. “Please inform Lieutenant Horloge that I require an audience with him immediately. I will be in my cell.”

“I’m not your errand boy,” Deloque says, looking up from his hoe.

“Then I will find him myself and tell him that you refused to pass on my message,” Cosette says.

“I ain’t afraid of that little flower,” Deloque says, but he turns and heads off in the direction of the officers’ quarters.

* * *

Lieutenant Horloge stops in the doorway of the cell, knocking on the door with a quick tap of his fingernails, no more.

Deloque towers behind him.

“This is for your ears alone,” Marie says.

“It does not matter what the private hears,” Horloge says, sniffing at a handkerchief stained with snuff.

“It matters to me,” Marie says.

Horloge looks at her haughtily, then at Cosette and back.

“Are you afraid?” Cosette laughs lightly. “An armed soldier, an officer in the French Army, afraid of two unarmed women?”

“Lock the door,” Horloge says to Deloque. “And wait at the end of the corridor. I will call you when I am finished.”

Deloque looks sullen, but complies.

Horloge watches to make sure he leaves and starts to turn back but stops as he feels the sting of a sharp point at his throat. One blade of the scissors. Deadly sharp.

“Call out and I will sever your artery,” Cosette says. “No surgeon will be able to save you. You will be dead in thirty seconds.”

“And you will be dead in sixty,” Horloge says.

“That is true, but you will still be dead,” Cosette says.

Horloge is silent and she takes that as a sign of compliance. Marie steps close and reaches for his pistol. Horloge drops a hand to his holster to stop her.

Cosette presses the blade harder into his throat, drawing blood. He gasps and moves his hand away.

“You will die for this,” Horloge says.

“We were to die anyway,” Marie says, withdrawing his pistol slowly, silently. She cocks the hammer with her thumb, checking the frizzen for powder. “Those were your orders, were they not? Once Willem had been found?”

Horloge is again silent. Cosette produces the other blade of the scissors and weaves a delicate line down the front of his tunic, to the region of his navel, then below.

“Perhaps! Perhaps,” Horloge says. “But your son has not been found.”

“That is not what we have heard,” Cosette says.

Horloge glances at the door, in the direction of Deloque. He sets his jaw angrily.

“What you have heard is only part of the truth. Your son and a group of other soldiers and spies landed near Antwerp. Most of them were killed or captured. But your son got away.”

“You lie,” Marie says.

“I tell the truth,” Horloge says.

“It does not matter,” Cosette says. “What has been started cannot be stopped. Call Deloque back in. Call him now.”

“I will not,” he says.

“Because of your duty? Your honor?” Marie asks. “Do as we ask and we will leave here, and you will have your life. Refuse, or try to fool us, or alert the guard, and you will die. There may be honor in dying on a battlefield, but there is none in dying in a prison cell at the hands of a woman.”

Horloge is quiet for a moment, then calls, “Guard!”

“A wise move,” Cosette says. “Perhaps you deserve a kiss for your trouble.”

She moves in front of him, embracing him, turning him away from the door, the blade pressed again into his neck. Marie slips quietly behind the door, the pistol in her hand.

Deloque, as Cosette has anticipated, is shocked at the sight of Horloge and Cosette locked in a romantic embrace. He unlocks the door and enters without a thought for Marie’s whereabouts, until her voice sounds quietly behind him.

“Give me your musket or I will sever your spine and if you live, you will spend the rest of your days as a cripple,” Marie says.

Deloque spins around, seeing the pistol aimed steadily at his midriff. He starts to raise his musket.

Cosette presses the blade even deeper into Horloge’s throat. He squeaks with the pain. “Do as she says. Don’t be a fool,” he says.

Deloque hands his musket to Marie.

“Against the wall,” she says, stepping back from the big man, the pistol steady.

Deloque obeys, crossing to a wall of the cell.

“You join him,” Marie says to Horloge, who also obeys.

“Now strip off your uniforms,” Cosette says. “And give us no trouble.”

Horloge stares at her for a moment before starting to comply. “Mademoiselle,” he says, “you may not think much of me, and I am not as much of a man as the soldiers that surround me. But I am no coward and I am no animal. I do not agree with women being used as pawns in this game. In all honesty I shall be pleased to see you free. You shall have no trouble from me.”

Cosette bows her head in thanks. His response seems genuine.

“I believe you are a good man,” she says. “I am not so sure of your companion.”

“I am still the commander of this garrison,” Horloge says. “The private will do as he is told.”

“Bind them tightly,” Cosette says to Marie.

A DESPERATE ACT

Deloque’s uniform is far too big for Maarten—Marie’s husband and Willem’s father—who seems much older than his years. A withered stalk of a man, brutalized by so many years in the stone-walled confines of his cell. Captured by the Fren

ch and forced to teach them his secrets of mesmerizing dinosaurs. He seemed unsure when they released him, unready to step outside the cell that had been the boundaries of his world for so long.

Still, with quick application of needle and thread, Cosette and Marie manage to stop the trousers from falling down and tuck up the sleeves. The tunic is so long it looks like a woman’s dress, but there is nothing they can do about that.

Cosette fits more easily into Horloge’s small uniform. The chest is tight and she feels squashed and short of breath, but it will be only for a short time. She will cope. She studies his face, thinking of all the shows she has performed in back in the village, and how features can be brought out with a little application of makeup.

She has no makeup here, and the application would have to be much more subtle to pass inspection at close quarters. She mixes a little dirt from the floor with dust from the walls, dampening it with spit.

Using the shiny blade of Horloge’s dagger as a mirror, she does the best she can to transform her face into his.

The first guard they must face is outside the door of the cell block. She might pass inspection but Maarten will never pass for Deloque.

She practices Horloge’s voice. It is deeper than hers, and his accent markedly different. However, he has a soft way of speaking that is easily imitated.

Maarten checks the bindings and the gags that secure Horloge and Deloque before he and the two women exit the cell, locking the door behind them.

Followed by Marie, then Maarten, who is clutching Deloque’s musket, Cosette marches to the end of the corridor and raps on the door to be let out. Maarten and Marie hang back, hiding in the doorway of one of the cells.

The guard checks through the barred hole in the door, as he is supposed to, before there is the click of a lock and the door opens.

Now is the moment, Cosette knows. Everything depends on this. She knows this soldier.

She coughs, covering her mouth with her hand. So far the guard shows no sign of alarm or recognition that she is anyone other than who she pretends to be.

“You are relieved, corporal,” she says, in her best approximation of Horloge’s voice. Even to her, it does sound like him. “Private Deloque will take over guard duties.”

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

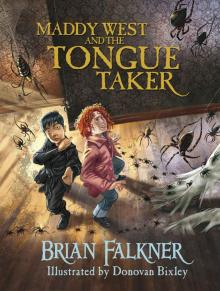

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker