- Home

- Brian Falkner

Clash of Empires Page 23

Clash of Empires Read online

Page 23

“Yes, sir,” the corporal says. “What is my new assignment?”

“You may take your rest,” she says.

“Thank you, sir,” the corporal says. He salutes and leaves.

* * *

The walk across the main courtyard of the abbey is a gantlet of potential danger. They pass by the huge doors of the storeroom, which is really a cover for the entrance to the caves beneath. One of the great doors is open and she can hear the grunts and smell the stench of the big animals in the cavern far below.

There are many soldiers in the courtyard. Any one of them could put an end to this charade immediately, noticing something odd about the captain, or the ill-fitting uniform of the guard who walks in front of him.

Out of the corner of her eye Cosette sees an adjutant approaching. This is a man who works every day with Horloge.

The other soldiers see Horloge mainly at a distance, but this man knows him personally. She panics momentarily, her hand straying toward the pistol in her holster.

She moves it away, thinking quickly, and pulls out Horloge’s handkerchief.

She waits until the man is quite near and turns to him, sniffing at the silk cloth.

“Sir, a letter from Calais,” the man says. “It just arrived. Most urgent.”

“Thank you,” Cosette says. She holds out a hand and the man hands her the letter, then salutes.

Cosette knows she has to return the salute but to do so would involve taking the handkerchief away from her face.

Again panic rises in her throat but at that moment Marie swoons, falling into the arms of her husband, the “guard” behind her.

The distraction is enough.

“See to your duties,” Cosette says. “I have matters to attend to.”

The man looks at Marie, and realizes. He pales.

“Of course, sir,” he says, spinning sharply on his heels and walking quickly away.

“Thank you,” Cosette whispers, as Marie stages a not-quite-miraculous recovery.

“Your performance is superb,” Marie says out of the corner of her mouth.

* * *

From his perch in the trees François sees three figures leave the main gate of the abbey and a cold sensation runs through him as though Satan has run his fingers down his spine.

The three figures leaving the abbey are a woman, followed by a guard, followed by the temporary commander of the abbey, Lieutenant Horloge. François has met Horloge and does not like him, finding him to be a weak, insipid excuse for a man.

The reason for François’s chill is the identity of the members of the party. The woman has to be Madame Verheyen, Willem’s mother. For her to be taken out in this manner can mean only one thing.

The last time François saw such a party it was to deal with a deserter. He was shot and his body dumped in a ravine, left for the saurs and other wild animals of the forest.

He slings his crossbow across his back and takes one of his rope walks to a different tree where he can get a better view.

From his new perch he can clearly see Horloge, his manner and gait are unmistakable, the angle of his head, the way he holds his hands. He is too high to see the face below the peak of the helmet, but he does not need to.

The guard is a new one. François has not seen him before. He is surprisingly old and frail for a soldier and François cannot imagine how he got posted here.

He lets them pass by, almost directly beneath his tree, then lines up his crossbow on the back of Horloge.

He almost fires, but stops himself. There is no point. If it was Cosette being marched to her execution, then yes, he would kill. He would take out the guard first, then the officer as he ran for help.

But this is not Cosette, just Willem’s mother. He has no feelings for her. None other than pity and that is not strong enough for him to want to cause the kind of ruckus that the disappearance of the commanding officer will cause.

He moves into another tree, no ropes needed here because the tree canopy is so thick that he can simply step from branch to branch.

It occurs to him that if Madame Verheyen is to be executed, then Cosette will surely be next. Unless the soldiers keep her to use as a plaything.

He shudders at that thought. It is against God.

He has feelings for Cosette and they have taken him a little by surprise. He sees her face when he closes his eyes for the night, and again when he wakes. Her shy smile, her lazy eye, they are the imperfections that make her perfect. Her wit and inner strength are also qualities to be admired.

Madame Verheyen marches to her death courageously, François thinks. Her head held high, her gaze proud and defiant.

He climbs easily down the knobbly trunk of an old oak and follows the trio, surprised when they do not turn off the path toward the ravine.

They reach the water hole and wait, while François watches, confused.

Then Horloge softly calls out, and it is not his voice but Cosette’s.

“François?”

And now he understands.

For caution he keeps the crossbow loaded and aimed as he emerges from the tree line.

The girl in the French officer’s uniform turns toward him and for a moment he thinks it really is Horloge. A little shading has been applied to her cheeks, and to her top lip to simulate Horloge’s embryonic mustache. With the helmet low over her eyes it is a good disguise.

“Cosette,” he says, and lowers the weapon as she takes three quick steps toward him, embracing him, tears now flooding.

“François, thank God,” she says.

“What has happened?” he asks.

“They say that Willem is dead,” Cosette sobs.

François looks quickly to Madame Verheyen, who nods. “Horloge denies it, but I think he would have said anything to appease us.”

François thinks carefully about what to say. To lie is a sin, but he has lied before, for the greater good. He knows that Willem has escaped, but the French hunt for him constantly. It is only a matter of time before he is found and put to death.

It would be cruel to so raise their hopes now, only to have them dashed later.

And the softness of Cosette’s skin feels so good against his.

“They are all dead,” he says. “An ambush near Antwerp.”

He does not explain how he knows this.

Now the man talks. This must be Willem’s father. The prisoner whom François has never seen.

“His death will not go unavenged,” Monsieur Verheyen says darkly. He seems weak and his wife quickly puts her arms around him to support him.

“Come,” François says. “We must hurry, before they discover you are gone.”

He strokes Cosette’s hair lightly. A gesture of sympathy, nothing more.

“Where are you taking us?” Maarten asks.

“To La Hulpe,” François says. “The priest there will hide us.”

“No,” Cosette says. “We go to Gaillemarde.”

“That is too close,” François says. “It will not be safe there.”

“After Gaillemarde we can continue to La Hulpe,” Cosette says.

“There is nothing at Gaillemarde to see,” François says softly.

“And that is what I must see,” Cosette says.

François considers this for a moment, then nods. “The search for you will be savage and thorough,” he says. “Perhaps Gaillemarde is for the best. There is a priest hole in the rectory. I used it to hide the children of the village when the French troops…”

He does not finish the sentence. He cannot. The massacre at the village is still a red raw scar across his heart, not least because he still wonders if somehow he was partly responsible for it. He has prayed to God many times about what happened at Gaillemarde, but God, so far, has chosen not to answer.

“The church was left alone,” he says. “We can hide in the priest hole while they search.”

GAILLEMARDE

The ride into Gaillemarde with Frost, Héloïse, and Arbuckl

e is perhaps the hardest thing Willem has ever done in his life.

Héloïse shares his horse. She was offered her own but declined. He knows why. She has never learned to ride. He feels her arms around him now, clinging, and he thinks it odd that a girl who is afraid of no wild thing is afraid of something so tame.

As they round a corner of the river and the gates of Gaillemarde come into view he eases his horse to the slowest walk and would stop, maybe even turn back, if not for the presence of the others.

He knows this place. He knows every stone in the road, every stunted shrub on the riverbank. He knows the loops and coils of the water in the river alongside.

He knows what he will find across the bridge and behind the saur-gates of the village. He can picture every house, every flower in every garden. Every face that will turn and smile to see him arrive.

And he knows he will not find this at all.

When they reach the shallow indentation in the ground where Cosette’s sister, Angélique, was taken by the greatest of all the saurs, he does stop. Staring at the rocky depression, still stained rusty red with her blood, he thinks, This is where it all started. If not for the monster, then the soldiers would not have come with their swords and their muskets.

When he gets to the bridge across the river he stops again. Unable to go on, unable to turn back. Caught in a kind of limbo between the world as it is and the world that once was.

This place is where his every memory was forged. Where almost everybody he ever knew lived their lives, making a living in the tranquillity of a country village, far from the intrigue and the politics of the capitals of Europe.

Just not far enough.

“Come, Willem,” Frost says. “They may be waiting for us.”

There are others who will surely be waiting for us, Willem wants to say, but does not. The spirits of all those who died. Will they blame him, staring with hollow endless eyes? Does he blame himself for what happened here? He has still not decided.

He glances back at Héloïse. Her gaze is fixed on the gates of Gaillemarde and he thinks she too is wrestling with memories and emotions. Arbuckle is nowhere to be seen, which is strange as he has been with them the whole way from Waterloo.

Willem nudges his horse forward, across the old stone bridge.

The saur-fence looks to be intact. The gates are shut but are blackened and burned, almost to the ground. The horses step over the remains.

Inside, it is worse than he feared. The pretty little village is a wasteland. A burnt-out hulk, swarming with weeds and vines. In just a few months the land has started to reclaim this village and no one has been here to stop it.

The lovely river cottages are still there. Their thatched roofs are gone but their stone walls have been unaffected by the fires that destroyed much of the village.

Frost stops riding. He lifts himself up in the saddle, listening.

“There are people here,” he says.

Willem looks around and sees no one, but he knows to trust Frost’s heightened senses. “Where?” he asks.

“I am not sure,” Frost says.

“Our people?” Willem asks, preparing to turn and run if not. Running into a French patrol at this stage would be disastrous.

“I don’t know,” Frost says. “But they don’t smell French.”

Willem has no time to ask what he means by this.

A trio of soldiers emerge from the remains of the tailor’s house near the gate.

Their uniforms are British, but so torn and muddied that they are almost unrecognizable. They carry a variety of weapons: muskets, pistols, swords. One has dark skin, almost black.

“Kill them,” an unshaven man says. He wears the uniform of a corporal. His expression is sullen.

Héloïse snarls at him and he draws back uncertainly.

Willem is suddenly very aware of the uniforms that he and Frost are wearing.

“We are not French!” he blurts out. “We are British soldiers.”

“More spies,” the man says. He raises his musket toward them.

“We are British,” Frost says.

“That’s what the last one said.” The man spits on the ground after speaking.

“Easy now, Noah.” The dark man steps forward. “They have not the accent of the French. Let us hear what they have to say.”

“I do not care to hear their lies,” Noah says.

Willem dismounts and helps Héloïse down, then steps toward the men, holding out his hands to show he means no harm.

The dark man moves forward. He is a large, strong man, and the others seem to respect him. He carries a Prussian cavalry saber. He places a hand on Noah’s shoulders and steps in front of him.

“Who are you?” the man asks. “What are you?”

He towers over Willem, who takes a step backward.

“What are you?” the dark man asks again.

“Mogansondram?” Frost asks.

The man steps closer, scrutinizing Frost. “Who are you and how do you know my name?”

“Corporal Mathan Mogansondram, if my memory serves me correctly,” Frost says. “I know your voice.”

The soldier studies Frost for a moment, then his face breaks into a huge smile. “It is I, sir. I know you also. You were the lieutenant that night. On the battlefield. After Waterloo. I did not recognize you straightaway, sir. You had rags around your eyes that night.”

“You would not leave your captain,” Frost says.

“He died, sir,” Mogansondram says. “I did what I could for him after that, then I left.”

He lowers his weapon and the others follow suit.

“A wise decision.” Arbuckle’s voice comes from behind the group of soldiers. He has a pistol in one hand and a saber in the other, inches from the neck of the unshaven soldier. Willem did not see him arrive and it is clear that nobody else did either. Arbuckle holsters his pistol and sheathes his sword, then offers his hand to the men, who reluctantly take it, one by one.

“How did you end up here?” Frost asks.

Mogansondram lowers his eyes. “I hid out in the forest for a while. I could not find the rest of my unit. I did not intend to desert, sir.”

“I know that you did not,” Frost says. “There was chaos after the battle.”

“Then I found this place,” Mogansondram says. “The others wandered in over the next few weeks. We hide when the French and Prussian patrols come.”

“How long have you been here?” Willem asks.

“I don’t know, sir,” Mogansondram says. “Perhaps a month. It is difficult to keep track of the days. What are you doing here, sir? And in French uniform?”

“That is a matter of great importance, and great secrecy,” Frost says.

“You said ‘more spies,’” Arbuckle says. “Have there been others?”

“Just one,” Mogansondram says. “He arrived this morning. He is tied up in the remains of one of the river cottages while we decide what to do with him.”

“Did he give you a name?” Frost asks.

“Hoyes,” Mogansondram says. “He claimed to be a lieutenant but his accent was not that of an officer.”

“He is indeed an officer,” Frost says. “And a very worthy one. I would ask you to untie him and fetch him here forthwith. Then I would like to enlist your help.”

“We would be honored, sir,” Mogansondram says.

THE SWAMP

The forest is alive with French troops. Many times the small group have had to duck into the undergrowth, frantically concealing themselves as soldiers on horseback, in twos and threes, prowl the tracks and pathways of the forest.

Each time they encounter French patrols it is only Frost’s exceptional hearing that gives them the warning they need to escape the oncoming danger. And it is Héloïse who is always able to find the best place to hide.

“Something is up,” Mogansondram says needlessly after a foursome of cuirassiers gallop past. “I have never seen so many patrols.”

“What ar

e they looking for?” Willem wonders.

“Us,” Arbuckle says.

“But how? Why?” Willem asks.

“Word of our mission has clearly reached French ears,” Arbuckle says. “That will complicate things.”

They wait in the shelter of a thick bush while Frost listens carefully to ensure that the riders are not coming back, and that no more follow.

After a moment Frost nods and they ease out of their hiding place. In the distance they hear dogs barking.

“Do not fear the dogs,” Héloïse says. “They do not know our scent.”

“That is good news,” Willem says.

“It is the demonsaurs we must be afraid of,” Héloïse says.

They reach the river and track along the stony bank for a while, walking in the edge of the water to hide their scent. They cross at a shallow ford and continue on the other bank. Several times Frost hears soldiers but Héloïse shakes her head. “They do not come this way.”

They pass the remains of an old jetty that Willem remembers from his last trip up this river. That time in a boat, hunting for a firebird. The river is exactly as he pictures it in his mind. A row of old rotten posts and collapsed timbers lined with ravensaurs staring at them with unblinking eyes, shaking dew off their long, leathery wings.

They are almost at a patch of giant, flowering ferns when Frost again pauses, pointing upriver. With an effort, Willem can hear it, too. The swish of a boat through the water and the sounds of oars.

“This way, and hurry,” Willem whispers. He takes Frost’s arm and pulls him toward the ferns, pushing through them, mindful of the edges, which from experience he knows are sharp and hard. He holds back as many of the ferns as he can as the rest of the soldiers swiftly pass through the opening.

On the other side is the swamp, just as he remembers it, and on the far side of that is the old shack. Crumbling stone walls with bushes and tall weeds sprouting up through the collapsed chimney. The roof and door are long gone, merely rotten remnants decaying in the humid swamp air.

The swamp buzzes with insects and burps with gas. It was here that they found Angélique’s body, if you could call what they found a body.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

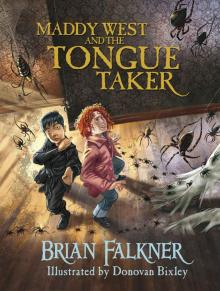

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker