- Home

- Brian Falkner

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Page 7

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Read online

Page 7

The body of the Maeroero, life spluttering out into the darkness of the tunnel, fell forward on the captive. The slayer became the shield.

The fight was short but violent. The warriors’ tactic was simple, but effective. They used the club end of their weapon to knock their opponent’s weapon arm down, and in the same fluid movement the knife end would spin around and bury itself in a chest, or a neck, or up under a chin.

They knew where to slice, and they knew where to stab, and in a whirl of flashing limbs and twisting bodies the smaller warriors cut a swathe down the length of the tunnel, the last few Maeroero facing attacks from two directions at once and having no chance at all.

Dark blood pooled in indentations, and seeped away into the dust of the floor.

And it was over.

Nine Maeroero were dead. One warrior also, and two more sat propped against the walls of the tunnel being attended to by their brothers in arms. The larger warrior used his weapon, still dripping with the blood of his enemy, to cut the bonds of the captive, and pushed the body of the would-be executioner to one side. The man sat up, rubbing his wrists. Then stood up. He was taller than the warriors and his features were sharper, his nose more defined. He was old.

The rest of the warriors were busy, lifting breastplates off the dead and dying Maeroero and plunging their long knives through their hearts. This was a battle with no prisoners.

The large warrior began an earnest discussion with the elderly captive and they both looked in our direction.

‘What’s happening?’ Jason’s voice behind me.

‘I’m not sure.’

The old man began to walk towards us. The warriors bowed to him as he passed. I stayed where I was. The bloodshed I had witnessed both sickened and frightened me and I found it easier just to lie still. The others, sensing that it was over, began to stir in the cave behind me and Jason joined me at the entrance just as the old man reached it.

He stooped and looked in our hiding place. He looked us over, more than once. He had picked up one of the Maeroero’s glowing crystal pyramids and its light filled the passageway around us.

He wasn’t all that old, I realised, probably late sixties. He still had most of his hair, and it was salt and pepper grey. He had a lean, grizzled, weathered look that I felt I had seen somewhere before. Stubble covered his chin as if he hadn’t shaved for a couple of days. His expression was kindly, but was there a spark of … madness? desperation? … glowing in the back of the deep wells of his eyes, or was that just a trick of the unnatural light.

‘Hello,’ he said, in perfect English.

I learned a little of the legends of Pachacuteq today and I thought I would jot it down. I don’t know whom, if anyone, will ever read this journal, but I think it would be important to record and understand the legends. Pachacuteq, possibly a mythological figure, or possibly a real person, is regarded as the creator of all Ukhu Pacha. Not a creator in the Godly sense, but more as a builder, a planner, the architect of the three cities.

When the cities were completed, it is said, Pachacuteq went wandering the tunnels of the great deeps, not to return until the next great change, the ‘Pachacuti’. Pachacuteq, according to legend, will arrive as a stranger, in the time of greatest need, when the walls of the great cities are crumbling. He will bring the power of ‘Inti’ with him. So far I have been unable to translate Inti’ as I have found no-one who can explain to me what it is.

The legends give few clues to help identify Pachacuteq when he arrives except for these: Pachacuteq will be a great warrior, able to defeat the strongest soldier of the strongest army without even a weapon. No ‘earthly blade’ can kill Pachacuteq. And “his victory shall be your victory also”. I think I have translated this last one right, although it doesn’t seem to make much sense.

To be honest it seems to me like pretty standard tribal legend, no different from those found in cultures all over the world. But understanding the legend helps me understand why the Runa people feared and respected us. They were simultaneously hopeful that one of us was Pachacuteq returned, and afraid that the Pachacuti was upon them. Probably we should have told them the truth a bit earlier than we did.

The legends are quite clear that Pachacuteq’s return signals the start of the Pachacuti. What the legends do not say is whether the Pachacuti will be a change for better or worse.

- from the Journals of Jenny Kreisler

7. Tukuyrikuq

By Jason Kirk

He began with his Runa name: ‘Tukuyrikuq’. It took him a long time to remember his English one.

The journey back from the outer tunnels, or nans, as we came to know them, using the Runa Simi word, had been an exhausting, wonderful, frightening, revelatory, mind-blowing series of eye-opening surprises.

In the space of perhaps twenty or thirty kilometres and just a few short hours, we learned things about this world we live on, that our surface-dwelling civilisation had never suspected. We started a path to solving mysteries that had puzzled mankind for centuries.

And frankly, most of the way we slept. The kind of numbing exhausted sleep the human body forces upon itself in times of great trauma. A self-healing mechanism I think.

There had been no chance to talk on the journey. Three of the warriors, including the big one, travelled with us on a swift flight through caves and tunnels they clearly knew as intimately as we knew the rooms in our own houses. Every time one of us tried to speak though, there was just the fist clamped across the mouth. I suspected the danger we faced was not yet thought to be over, and after the first few attempts we all just scurried along with the old man and the warriors, sometimes through twisting, winding caves, and other times through long flat passageways.

Eventually we emerged into one of the Great Nans, huge artificial thoroughfares tunnelled through the rock. Originally wild, ragged channels that had been tamed and smoothed by the hand of man.

The floor was dead flat and smooth as concrete. The walls rounded into an egg-shell curve. A path of glowing shili crystals, huge sheets of them, lined the apex at the centre of the roof and stretched as far as we could see in each direction, providing a soft light for the entire Nan.

We emerged though a circular hatchway that the big warrior ‘unlocked’ using an oddly shaped stone he carried on a cord around his neck. He locked the hatch again behind us.

The Nan was almost deserted, except for the rear of a cart-like vehicle in the distance that eventually disappeared around a sweeping curve, it was pulled by some large animal but at the distance I could not see what it was.

We were exhausted. Exhausted beyond the limits of conversation, beyond the limits of comprehension. Six kids from Glenfield stood on an underground road in the company of three semi-naked warriors and one old man who spoke English, and I thought that life could not get much stranger.

It was about to.

The big warrior spoke rapidly to one of the others, a female, who pulled out two small sticks from somewhere in her armour. She moved to a long thin tube that ran the length of the Nan at about head-height, and put her ear to it, listening. Apparently satisfied, she began to tap on the tube, using the sticks. An irregular pattern, full of starts, stops and small intricate riffs. After that she put her ear back to the tube and listened for a moment. She spoke briefly to their leader, and we were on our way.

The walking was easier here, although stumbling would have been a better word for our method of locomotion. I had lost track of time. My watch had survived the earthquake and it said ten past five, although I couldn’t have told you if that was ten past five in the evening, or if it was the next morning, or maybe the evening after that.

We walked for an hour, not realising that the warriors had arranged some transportation to meet us. When it came, I almost cried out in shock. I think I would have if I hadn’t been so exhausted.

A cart appeared in the distance in front of us, similar, I thought, to the one we had already seen. The creature pulling it had an odd g

ait, and I realised after a while that it was two-legged. I suppose I had been expecting a donkey, or a small horse.

As it approached, we could see that the body of the animal was rounded, the legs were massive, ending in huge, three-toed feet. It was pure disbelief that made me take so long to recognise the creature for what it was. It wasn’t until it was almost upon us, its long neck swaying slightly from side to side in the harness that attached it to the cart that my mind accepted what my eyes were telling me. It was a bird. A giant bird. A huge, wingless, feathered bird, and in the state I was in, it didn’t take me more than a few more minutes to remember the name of the bird, for I had seen many pictures in school, and seen the life-sized model at the museum.

The Runa people called it a paqocha. Scientists called it a dinornis giganteus. We commonly used a different word though: Moa.

To make some allowance for my apparent lack of intelligence, you need to understand that the Moa’s we had seen in pictures and in museums were tall, perhaps three metres high. This bird could certainly have stretched that high, but it didn’t. The long moa neck was in front of the massive body in an s-shape, holding the head at about the same height as the back. Still about two metres off the ground though, taller than Fizzer. The eyes were black but reflected greenly the light of the tunnel in the sides of the (relatively) small head. Steering was a couple of cords, I suppose you could call the reins, which simply pulled the bird’s head in the direction you wanted to go. The driver, a girl, quite young but with different facial features to the warriors and taller than any of them, turned the whole contraption around on a ten cent piece and we were gently bundled onto the cart. The driver was dressed, not in the black battle armour of the warriors, but in a soft, translucent robe,

I wanted to talk then, but the old man gently put his fist to his lips and the exhaustion, plus the gentle swaying of the cart, finally won the battle with the adrenalin and the fear, and the rest of the journey passed without any awareness or assistance from me.

I awoke on a soft bed. It took me a while to re-gather myself and recap over the events of the last day or so, trying to sort out what was real from what was just a bad dream. Rather unfortunately, I reflected, it had all been real. A bad dream would have been infinitely preferable.

The bed was just a mattress on the rock floor of a sleeping chamber. Imagine a square hole half a metre high, by the same width, the length of a man, cut horizontally into the face of a flat rock wall. That was a sleeping chamber. The mattress was a light, spongy material, not un-like foam rubber and smelled vaguely of the ocean.

I could reach up and touch the roof of the sleeping chamber, a fact which rapidly brought on a small attack of mild claustrophobia and I scrambled out, dropping down to the floor of a larger room.

My sleeping chamber, I saw, was one of nine, arranged in a noughts and crosses square, three chambers high by three across, an efficient way of sleeping a number of people in a small space.

There was a low table in the room, but no chairs. Flea was awake, seated, eating some kind of gruel from a flat bowl. Fizzer was meditating in the corner. Of the others there was no sign, although the rumble of Tupai’s snoring came from one of the holes. The roof of the room was low. Only Flea, the smallest of us, could stand in it without stooping. Space in this world, clearly, was at a premium.

Flea looked at me, and about three hours of conversation passed between us in a single glance. Amazingly, incredibly, we were here. It had been real. The caves were real, the battle had been real, the earthquake had been real and our sensei, Dennis, was dead. That was real too.

A girl entered; alerted I think, by the noise I had made clambering out of the bunk-like chamber. She was of the smaller race, with the high, regal forehead, and the more aquiline nose. Her lips were generous in the otherwise delicate face. She was breath-takingly beautiful, although it still took me some time to get used to the too-white skin.

She brought a bowl of gruel for me, and smiled pleasantly, if a little nervously. She bowed deeply, and then bowed again before departing.

‘You must be privileged,’ Flea smiled with his mouth full. ‘I didn’t get a bow.’

Fizzer opened his eyes. ‘There’s a certain reverence whenever they appear to be talking about you.’

I nodded, a little surprised, and slightly concerned, and changed the subject.

‘Where the hell are we?’

Flea stopped eating. ‘Don’t worry about it. Get some food into you. The old guy has already popped his head in the door once. He wants to talk to us, but I think he’s waiting until we’re all awake.’

Fizzer said with quiet intelligence, ‘Or maybe he’s just waiting until you’re awake.’

I asked, ‘Have you been for a look around?’

Flea shook his head. ‘There are two soldiers outside the entrance. They’re dressed in robes, but you can still see the shape of the armour underneath, and they are carrying those weapons.’

‘Taiaqha,’ Fizzer contributed. ‘They call them Taiaqha.’

I looked quizzically at him and he said, ‘I’ve been trying to pick up what I can of the conversation, from Paculi and other bits I’ve overheard.’

‘Paculi?’

‘The pretty one, brings the food.’

I nodded. Paculi. I mouthed the name, liking the way it made my mouth move, liking the physical feeling of the language.

Fizzer said ‘They call you Pachacuteq.’

I asked, a little confused, ‘And you? And the others?’

He shook his head. ‘Just you. But …’ he paused and looked sideways at Flea. I had the impression they had already discussed this. ‘… I’m not entirely sure it’s a good thing.’

Pachacuteq.

We were interrupted by Jenny, climbing out from one of the lower chambers. She rubbed her eyes and tried to run her fingers through her long, auburn hair, which was matted like straw. She gave that up after a moment, and Paculi arrived on cue with the customary bowl of gruel.

I realised, quite suddenly, how hungry I was, and tucked into my own bowl as Jenny went through pretty much the same conversations with Flea and Fizzer that I had just had.

The gruel was surprisingly pleasant. A sweet porridge, with a faint spiced flavour. It was filling, and invigorating, although that may have simply been the effect of having food in my stomach again.

Flea glowed around Jenny. A life came to his expression that was not there when she was not around, and which was the exact inverse of the dullness that glazed his eyes when she and Phil were together. He was in love with her, I realised, even if he wouldn’t admit it, even to himself.

Tupai rolled out of bed while we were eating, and that left only Phil, lightly breathing in the bottom left chamber as his body tried to repair the damage that had been done to it.

Even he was up though, eating his gruel, his multi-coloured leg propped on a soft cushion that Paculi had brought without being asked, by the time the old man returned.

We were all dressed in the soft robes of the Runa. I didn’t remember changing, but then I remember little after being bundled into the Moa-cart.

Paculi brought Tukuyrikuq a cushion also, and he eased his tall frame onto it, with a little assistance from her. She smiled at all of us and left. The man looked around the low table at us, and waited patiently for Phil to finish eating before speaking. I thought that might be a custom. Runa table manners. Or maybe he was just trying to formulate the words.

When he spoke it was as if he were dredging the language up from some long distant part of his memory. He spoke with a slight English accent, but the words did not come naturally to his lips. A language, once native, now only half remembered.

‘I am Tukuyrikuq,’ he said falteringly at first but growing in confidence. ‘I had an English name once, but it escapes me now.’ He closed his eyes for a moment and smiled, then said, ‘I have … I am … very old now and I have not used these memories in a great many years.’

Phil started to ask s

omething, but I silenced him with a quick shake of my head. ‘Let the man speak’, I told him with my eyes.

Tukuyrikuq continued, ‘Answer me this question, and answer it truthfully, but if anyone else asks you the same question, you must be guarded in your response. Do you understand? Do you …’ he struggled for a word, but either he couldn’t remember it, or there simply wasn’t one in English to express the concept, ‘do you understand?’ he repeated.

I spoke on behalf of the group, and with their assent, I could tell from their eyes. All except Phil that was who only glanced sullenly at me, and then looked back at Tukuyrikuq.

‘We understand.’ I said.

Tukuyrikuq gathered his breath, or his courage, and asked ‘Are you sky-dwellers? Are you from the surface?’

I nodded and started to say ‘yes’, but he hushed me with a small fist to his mouth.

‘I thought so. Now forget what you have told me and never speak of it again. Not to the Runa, not to the Amori. Not to the Grypthi of the Nor’east, nor the Panaka of the City of Gold.’ He smiled, ‘only the Maeroero would not care, as they were eating your hearts.

These people are nervous about you. Please understand that the Runa have no concept of the surface, of the world you are from. They would say you are gwei-teri, demons from Kay-Pacha, the “above-world”. Kay-Pacha, in English,’ he stopped, searching for the word. Then his face creased with remembrance, ‘In English the word is “Hell”.’

There was a kind of numbed silence, and I remembered the great black gates, as he continued, ‘There are others here, who believe that you …’ he looked directly at me, ‘… that you are Pachacuteq, returned from wandering the great deeps. But even that makes them nervous for, if that is true, then the coming war with the Maeroero is merely a prelude to the next Pachacuti, the time of great change.’

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

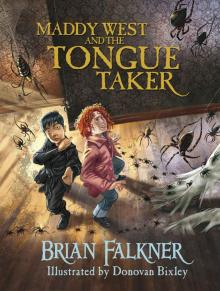

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker