- Home

- Brian Falkner

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Page 8

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Read online

Page 8

He laughed. ‘Myself, I don’t believe in Pachacuteq, but then I am Tukuyrikuq, the all-knowing-one. I helped invent the legend, or at least to give it some colour, as it is an ancient legend. For now just understand this. If the Runa think you are from Kay-Pacha they will puncture your hearts without remorse, for they will know that you are demons. If they think that you,’ again he looked at me, ‘are Pachacuteq, they will expect you to advise and guide them, and lead them into battle. If you tell them you are, and they find out you are not, they will take your life, and those of your friends, without compunction. Your choices are somewhat narrow, my friend.’

‘August,’ It was Phil, with that raised eye-brow of his. ‘Randolph August. You are Sir Randolph August. That is your English name isn’t it?’

I started to interrupt. If August had gone missing in 1926, and had been even in his twenties at the time, he would be over a hundred years old now, and Tukuyrikuq did not look much more than late sixties at worst.

The old man looked surprised, but shook his head. ‘Sir Randolph August. No, damaged-one, I am not Sir Randolph August. And yet, I know this name, from the deepest dredges of my memory, I know this name. Sir Randolph August. I think… I think he was my friend.’

‘In that case,’ Phil said triumphantly, ‘You are Graham Mallory.’

The old man brightened. He turned the name over a few times. ‘Graham Mallory. Graham Mallory. Certainly that is the name I had as a child. Graham Mallory.’ He looked around the group. ‘I am Tukuyrikuq, but I once was Graham Mallory.’

There was a silence as we digested that piece of news. If it were true, then people underground aged a lot more slowly than people on the surface. I suppose that was possible, without the damaging rays of the sun. It seemed appropriate to introduce ourselves at that point and I did the honours.

Mallory – Tukuyrikuq – spoke directly to me, ‘Until they find out who you are, they will treat you as Pachacuteq. Just in case you are. You have already been assigned a yanakana, a servant. Keep your faces closely shaved. I will find you some small blades for this purpose.’

I noticed that the stubbly growth he had sported yesterday was gone. He saw my eyes flick down and smiled, ‘I can get away with certain things because of my age, and my history with the Runa, that you cannot. Demons have hairy faces. If you do not bare your face, they will see you as demons and slaughter you like atrophoq. You will find a var-shavi, a communal washing facility down the street to your right.’

Tukuyrikuq stopped and retreated into himself for a moment. We were silent. Somehow there were a thousand questions but nothing to say. After a while the old man continued, ‘In a day or so you can expect to receive an invitation from the king to visit the royal palace in the great walled city of Contisuyo. Until then you are the guest of the Taytacha-Raki, here in the city of Raki.’

His face grew grave. ‘In Contisuyo you will meet with priests, important religious leaders: Amatua. It is the Amatua who will decide if you are telling the truth, about who you are. If I may be permitted to make a suggestion, I think it might be safer for you to return to the surface before then.’

I heard Fizzer mutter, ‘No argument from me.’

But it was lost as Tukuyrikuq made a request that, in a crashing second, bought a cold grey hopelessness to our hearts and sent our slowly reviving spirits on a whirling pathway to destruction. The old man asked us, ‘If you go. I beg of you. Please show me the way.’

I once read a book about early civilisations in New Zealand. Its title was “People Before”.

It talks of the archaeological mysteries that abound in New Zealand. A stone adze found beside a Kauri stump, beneath a 20,000 year old lava flow. A metallic disc found embedded in a 50,000 year old rock. Metallic!

It is clear to me now that prior to the European settlement of New Zealand, prior even to the great Maori migration, there were open pathways into Ukhu Pacha. From the great moas that are bred here for transport, food and battle, there is little doubt that in ancient times the surface and the underground were as one.

- from the Journals of Jenny Kreisler

8. Tupaq

By Jason Kirk

Strange, the ways and customs of the Runa. Strange to us, I suppose as we came from not only a completely different culture, but a completely different world. Same planet, different universe. Strange, the food. Strange, the language. Strange, the legends and myths.

Strange that a welcome feast could end up in a challenge, a Tupaq, a fight to the death. Strange.

We were indeed the guests of the local ruler, Taytacha-Raki, and he had decided to celebrate our coming in style. I didn’t know whether this was because we were mysterious guests from some unknown cave, or because he wondered/hoped that I was this mythical, messiah-like figure of Pachacuteq.

Before the feast, of course, we had to get cleaned up. Wash the earthquake dust out of our hair.

The var-shavi turned out to be a large communal room with individual washing holes. The holes were scooped out of the rocky floor in a bath-like shape and had a constant flow of warm water, in through the top and out through the feet end of the bath. There must have been thirty var-shavi (the name of the room was also the name of the washing hole) in the room. Each had its own supply of fresh, clean water, running through channels on the rocky floor. Neither water, nor warmth, seemed in short supply here, the water came, I guessed, from underground rivers, and the heat from thermal activity, although we later found out that the Runa had a ready supply of natural gas and were very advanced in its use for heating.

The var-shavi was an unexpected luxury. You lay in the shallow hole and the warm water washed over you. It was like bathing in a warm mountain stream. A soap-like substance was available in small clay pots at the door.

The var-shavi facility was communal, and unisex. Men and women, old and young, shared the same open space. There seemed to be no modesty, no shame at the open nudity, a fact that caused us a little embarrassment when we visited the var-shavi for the first time.

Jenny broke the ice, once we had realised the workings and the conventions of the facility. ‘When in Rome,’ she muttered, stripped off and plunged into the nearest bath.

Phil glared around the group as if daring us to look, but it was out of respect for Jenny, not fear of Phil, that I averted my eyes and found a free bathing hole for myself.

The water was deliciously warm and cascaded over you in a relaxing, mild buffet. The constant flow of clean water made me wonder about the wisdom of our own bathing customs above ground, where we would sit in a bath full of dirty water. The soapy substance seemed to work as effectively on hair as it did on skin, and I shaved with it also, using a pocket-sized knife that Tukuyrikuq had given us. What passed for towels were hanging everywhere on long hooks suspended from the low rock ceiling. Not towels at all, they were long sponges, made of some close relative of the mattress material. They soaked the water off your body very effectively.

I observed the locals’ custom of rinsing the sponge thoroughly in the running water of the var-shavi after use, ringing it out, then hanging it back up to dry, ready for the next bather.

Please show me the way.

Tukuyrikuq had had over eighty years to find a way back to the surface, and he had asked us the way out. We hadn’t replied. Too much in shock I think. Too worried about ourselves to think of this man who had not seen the blue of the sky for the greater part of his life.

Please show me the way.

Were we trapped also? Condemned to spend the rest of our lives underground? Tukuyrikuq told us he had been heading to the Gates of Hell when he had been captured by the Maeroero raiders. He had hoped that the Earthquake might have opened up an entrance to the surface. In a way I suppose it had, just not for very long.

When you go. I beg of you. Please show me the way.

The roof was low in the var-shavi facility and I banged my head, hard enough to hurt, as I dried myself after the bath. Tupai’s squat shape was hunched ov

er, and I saw that tall Fizzer found it easier to sit down to dry himself off with the sponge, rather than to crouch under the low roof.

We had a full honour guard to escort us to the feast. Lunch? Dinner? It might have been breakfast for all I knew. Time seemed to run on a different set of rules here underground. Because, I supposed, of the lack of a night or day.

The honour guard consisted of twelve tall, strong soldiers. Their battle armour was ceremonial, gold and silver, instead of the more functional black armour they wore on patrol. Their face-masks were inlaid with precious stones, but had the same winged edges as the ones we had seen previously. I recognised one of them from his voice, as the tall warrior from the caves. His name, I was to find out much sooner than I would have hoped, was Turiz.

We marched at a slow pace through the thoroughfares, the nans, of Raki on our way to the Taytacha’s mansion. In the lanes and in alcoves to each side we observed a constant, urgent activity. People were packing belongings into carry-bags. Walls were being built, or reinforced by stacking flat, rectangular rocks on top of one another. Troops of warriors, in full battle gear, were training in small courtyards. Even to outsiders such as ourselves, unfamiliar with the life and the customs in this strangest of cities, it was clear that these people were preparing for war.

The activity stopped as we passed, and many Runa cast suspicious glances in our direction. Others bowed deeply. Demons or saviours, I thought. Gwei-teri or Pachacuteq. They were not sure.

There seemed to be a broad mix of ethnicity amongst the people, although with some careful observation and deduction I eventually narrowed it down to two primary races, the taller, more Polynesian, or possibly Melanesian looking race, and the smaller, more regal-featured people. The others, I surmised, were all the result of inter-marriage between the two races. The word Runa, we eventually discovered, although used as a general word for the population, actually referred to the smaller race. The larger people were known as Amori. By sheer weight of numbers the dominant race had to be the taller one, outnumbering the smaller race by three or four to one, which made it a little surprising that Runa was the generic term. Most of the soldiers we saw, for some unexplained reason, were of the smaller race. There seemed to be no class distinction between the races, that I could see. For that matter there seemed to be little or no distinction made between the sexes, men and women doing the same work, even as soldiers, as we had noted earlier.

Taytacha-Raki turned out to be a plump, jovial fellow, with an appetite as hearty as his sense of humour.

We were welcomed into his impressive eating chamber with a blast of sound, a fanfare I suppose you’d say, on short, curved horns. Impressive, because of the size, and the high ceiling, about two metres. Even Fizzer could stand upright without having to stoop. The food was provided on a series of large, round tables, low to the ground as before. There were no chairs. The six of us, plus Tukuyrikuq, and two Amori women – two of the Taytacha’s favourite wives, I later discovered – were seated at the largest of the tables at the far end of the room.

A musical ensemble provided the dinner music, playing in a corner of the room on a series of mandolin-like instruments of varying sizes.

The Chamber Quartet, Phil christened them, although there were at least twelve of them, plus pan-pipes and some kind of ‘bongo’ style drums.

The music was lively and exuberant, like the people, and if a leader should be the pinnacle of his people’s personality then the Taytacha-Raki succeeded , as he was the most lively and exuberant of them all.

He was of the Amori, the taller race, and judging by his features he was a pure-blooded member of that race. He had the same white skin as the others, a fact that Jenny put down to a lack of melanin. Biologically unnecessary under the earth, where there was no sun.

Conversation over the meal was slow, due to the constant translations required by Tukuyrikuq, but our host’s constant good humour, and a little patience on behalf of all of us, made it a surprisingly pleasant occasion.

For the sake of brevity I have removed the translations from my record of that feast, and left only the conversations that took place.

‘Welcome traveller, to our great city of Raki, jewel of the North,’ the Taytacha proclaimed.

I noted his use of the word ‘traveller’, rather than ‘travellers’ and that he looked only at me as he said it. Pachacuteq, according to Tukuyrikuq, had gone wandering the ‘great deep’s of the underworld. I wondered if there was more to this simple welcome than met the eye.

I answered for our little band, aware out of a corner of my eye, of a glare from Phil as I did so. ‘We are privileged, and humbled by your welcome, and your generosity,’ I said. It sounded lame, and I trusted Tukuyrikuq would translate it into something a little more grandiose and appropriate.

Serving men and women, waiters I suppose, served a muddy looking drink in glass tumblers. Flea caught my eye as they placed the small glasses in front of us, and I read his thoughts. Glass! The Runa had glass. I couldn’t remember how you made glass, except that it was something to do with sand and heat. But it implied a higher level of technology than we had guessed at.

The drink was vaguely chocolaty in flavour and mildly intoxicating. It was called Kintu, although I didn’t find that out until later. Aware of the danger of any of our party making fools of themselves, I said, ‘Go easy on the drink guys, don’t get drunk.’

There was an embarrassing silence, and all eyes were on me. I realised that speaking to my friends in our own language, with a translation, was somehow insulting to the ruler.

I stood, raised my glass to the Taytacha, and in the manner of giving a toast, repeated my words.

My friends stood and unanimously, hilariously, repeated my words as if they were a solemn toast. There was a little consternation around the room, then Tukuyrikuq stood and, with a small, subtle wink to me, raised his glass, and spoke the same words also, ‘Go easy on the drink guys, don’t get drunk.’

The Runa latched on to the custom rapidly and to a man, the population of the large eating chamber rose, nobles, priests and other Important Guests, raised their glasses to the Taytacha, and in a variety of levels of ability proclaimed, ‘Go easy on the drink guys, don’t get drunk.’

I bit back a smile and saw Jenny doing the same. Tupai was just about exploding, trying not the laugh.

Other than that, Tupai was silent throughout the great feast. In fact he’d hardly said a word since the earthquake. He was unusually quiet for a normally cheerful and expressive personality, and I eventually realised why: he had lost his hearing aid in the earthquake.

Not that it would have mattered much anyway, as the battery wouldn’t have lasted long and he could hardly pop down to the dairy for a new one.

The hearing aid was an unfortunate memento of the one fight Tupai hadn’t won. The only one he had ever lost, as far as I was aware.

It had taken three of them though, and it had been a savage beating. Sadly, they had been his three older brothers.

The chocolaty drink was followed by the first course of the feast. I won’t bore you with details of the food, except to tell you this: Bat tastes like smoked chicken. Roast Moa is stringy, chewy and a little like over-cooked pheasant. Eel pie tastes like eel pie, wherever you are in, or under, the world, and there are such things as edible spiders, but if you are offered any, avoid them. I didn’t try the boiled cave-wetas.

What do you talk about to the ruler of an underground city? All the common conversation starters we took for granted were out of the question, or out of bounds down here. We couldn’t talk about the football, the latest TV programmes, people we knew, or what we were going to be doing next year. And we sure as hell couldn’t talk about the weather!

So what do you talk about to the ruler of an underground city at a feast in your honour. The answer, and it was Phil who supplied it, was: whatever you have in common. And there was one thing that we did have in common. The earthquake.

No one had been kill

ed when the earthquake had struck Raki, and there had been no serious damage, and that made the whole affair a matter of some levity. We didn’t feel quite the same way about the events, but were swept along with the mood of our host.

Taytacha-Raki had been in the var-shavi at the time and two things immediately emerged from his description of events. Firstly, his var-shavi was private, and a far cry from the plain rocky var-shavi of the general populace. The Taytacha’s var-shavi, apparently, was solid gold and lined with rare black crystals. The water flowed from the mouth of a god, again shaped from solid gold, and there were never less than three of his wives to assist with his bathing. Nice for some. The second thing was that he was inordinately proud of his var-shavi, but you might have guessed that already.

The Taytacha’s hands shook in the air as he described the walls of the var-shavi trembling during the quake, water sloshing and spraying everywhere and quite drenching his attending wives. One of them was obviously at our table and he patted her affectionately on the arm as he described that part of the story.

He himself, he told us, lay there and clung to the sides of the var-shavi for dear life. He hooted with laughter as he described his fearful face. Then in front of the nobles, priests, distinguished guests, and possible returned-saviours, he opened his elegant robes and bounced up and down on the floor, demonstrating to us how the quake had made his fat quiver like so many layers of jelly.

The whole room roared with laughter, and the Taytacha, ever a glutton for an audience, went through the whole story again.

The affection for him in the room was genuine, as far as I could tell. Whatever his style of ruling was, his people loved him. Smile, they say, and the whole world smiles with you.

I didn’t regard myself as a natural communicator, and neither, really, did Flea or Jenny. Tupai was, but without his hearing aid he had withdrawn into himself, only catching parts of Tukuyrikuq’s translation in the cheerfully noisy room. Fizzer, quite garrulous amongst friends, was always a little reserved among strangers, and seemed to spend most of his time and concentration studying the various personalities, and the body language as conversation ebbed and flowed around the room.

The Real Thing

The Real Thing Task Force

Task Force The Flea Thing

The Flea Thing The Project

The Project Clash of Empires

Clash of Empires The Assault

The Assault Brain Jack

Brain Jack The Tomorrow Code

The Tomorrow Code Vengeance

Vengeance The Super Freak

The Super Freak Northwood

Northwood Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1)

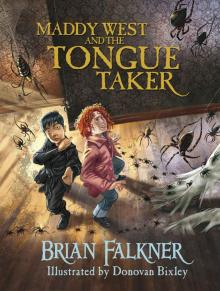

Cave Dogs (Pachacuta Book 1) Maddy West and the Tongue Taker

Maddy West and the Tongue Taker